Here is a confusing mixture of a “Cryptoid” defining “cryptid.”

May 3, 2011

Beth McCarley asked on Facebook: “Could anyone explain the difference between the words ‘cryptid’ and ‘cryptoid’? Thanks!”

Until recently, there was no such formal term, “cryptoid.” It appeared to a mistaken word employed by those who wished to have more properly used the correct word, “cryptid.”

Here is a confusing mixture of a “Cryptoid” defining “cryptid.”

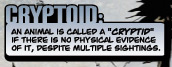

However, since 2007, in the comic book Proof, the term “Cryptoid” is used like the word “factoid,” to convey a meaning to a word being defined. The critique site “Freak Comics” does not approve of the use of “cryptoids,” and notes so here. They write: “The most glaring mistake in this comic is the Cryptoids. Cryptoids are an annoying comic book version of VH1′s pop-up video. I could almost hear the obnoxious bubble popping sound each time I read a Cryptoid. Although these were meant to help drive the story forward and keep you informed, they only slow the story down. One or two of them may not have been so bad, but the Cryptoids appear throughout the issue. It’s like a constant barage of footnotes in a novel… rather annoying. These so-called Cryptoids would be better served as a traditional narration box.”

I defined “cryptid” in my book, Cryptozoology A to Z, as follows:

“Cryptid” is a relatively new word used among professionals and laypeople to denote an animal of interest to cryptozoology. John E. Wall of Manitoba coined it in a letter published in the summer 1983 issue of the ISC Newsletter (vol. 2, no. 2, p. 10), published by the International Society of Cryptozoology. Recently “cryptid” was recognized by the lexicographers at Merriam-Webster as a word of legitimate coinage, though it has yet to appear in their dictionary, as of 1999.

Cryptids are either unknown species of animals or animals which, though thought to be extinct, may have survived into modern times and await rediscovery by scientists. “Cryptid” is derived from “crypt,” from the Greek kryptos (hidden); “id,” from the Latin ides, a patronymic suffix; and the Greek “ides,” which means “in sense.” When the suffix id is used it typically applies to an implied lineage or similar usages, as in “perseid” (meteors appearing to originate from Perseus, typically around August 11).

Bernard Heuvelmans’s definition of cryptozoology itself was exact: “The scientific study of hidden animals, i.e., of still unknown animal forms about which only testimonial and circumstantial evidence is available, or material evidence considered insufficient by some!”

Over the pre-turn-of-the-century decade (i.e. 1989-1999) some have suggested that the science of cryptozoology should be expanded to include many animals as “cryptids,” specifically including the study of out-of-place animals, feral animals, and even animal ghosts and apparitions. In the journal Cryptozoology, Heuvelmans rejects such notions with typical thoroughness, and not a little wry humor:

Admittedly, a definition need not conform necessarily to the exact etymology of a word. But it is always preferable when it really does so which I carefully endeavored to achieve when I coined the term “cryptozoology.” All the same being a very tolerant person, even in the strict realm of science, I have never prevented anybody from creating new disciplines of zoology quite distinct from cryptozoology. How could I, in any case?

So, let people who are interested in founding a science of “unexpected animals,” feel free to do so, and if they have a smattering of Greek and are not repelled by jaw breakers they may call it”aprosbletozoology” or “apronoeozoology” or even “anelistozoology.” Let those who would rather be searching for “bizarre animals” create a “paradoozoology,” and those who prefer to go a hunting for “monstrous animals,” or just plain “monsters,” build up a “teratozoology” or more simply a “pelorology.”

But for heavens sake, let cryptozoology be what it is, and what I meant it to be when I gave it its name over thirty years ago!

Unfortunately, many of the creatures of most interest to cryptozoologists do not, in themselves, fall under the blanket heading of cryptozoology. Thus, many who are interested in such phenomena as the so-called Beasts of Bodmin Moor (not unknown species but a known species albeit in an alien environment) and the Devonshire/Cornwall “devil dogs” (not “animals” or even “animate” in the accepted sense of the word, and thus only of marginal interest to scientific cryptozoologists) think of these creatures as cryptids.

More broadly, then, we do not know whether a cryptid is an unknown species of animal, or a supposedly extinct animal, or a misidentification, or anything more than myth until evidence is gathered and accepted one way or another. Until that proof is found, the supposed animal carries the label “cryptid,” regardless of the potential outcome and regardless of various debates concerning its true identity. When it is precisely identified, it is no longer a cryptid, because it is no longer hidden.

While Heuvelmans created cryptozoology (independently, and later than the coining of the word by Ivan T. Sanderson – shown at left) as a goal-oriented discipline (endeavoring to prove the existence of hidden animals), the fact that some of these cryptids will turn out not to be new species does not invalidate the process by which that conclusion is reached and does not retroactively discard their prior status as cryptids. For example, the large unknown “monster” in a local lake is a cryptid until it is caught and shown to be a known species such as an alligator. It is no longer hidden and no longer carries the label “cryptid,” but that doesn’t mean it never was a cryptid.

It is often impossible to tell which category an unknown animal actually inhabits until you catch it. Until then, it is a cryptid.

The definition (with new notes) is from Cryptozoology A to Z (NY: Fireside/Simon and Schuster, 1999) pp. 75-77.

++++++

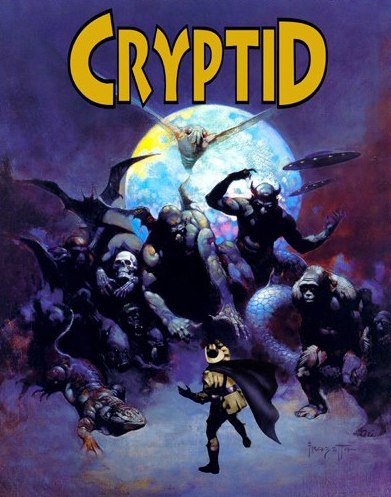

Today, in 2011, it is remarkable the explosion of sites, films, books, and other items that are using the word “cryptid” to inform customers immediately of the content of their product. Here are some examples:

![]()

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, Pop Culture