Takitaro

Posted by: Loren Coleman on December 8th, 2009

Takitaro

By Brent Swancer

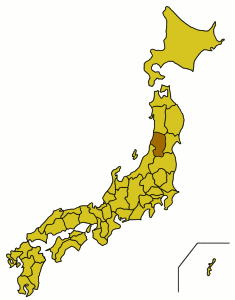

In Yamagata Prefecture on Honshu island, Japan, there is a small, isolated body of water by the name of Otori-ike 大鳥池, which lies high in the mountains, 1,000 meters above sea level. Despite its Japanese name (“ike” means “pond”), the limnology of Otori-ike is not that of a pond. It is in fact a lake, created when a landslide blocked off a mountain stream long ago. The lake is 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) around and 68 meters (223 feet) deep at its deepest point. Located within Yamagata’s largest virgin forest, Otori-ike is known for the area’s stunning natural beauty, and is a haven for hikers.

The lake is also known for a perplexing natural mystery. Otori-ike is said to be the home of giant fish lurking within its depths; fish known locally as takitaro.

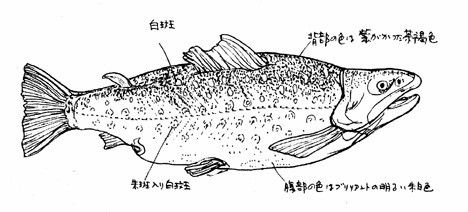

This is a diagram showing the size of a Takitaro next to a human for comparison.

The Takitaro are said to be enormous fish capable of reaching sizes of up to 3 meters (10 feet) long. Locals have long told of seeing these giant fish in Otori-ike, and the creatures are well integrated into the folklore of the area. Takitaro were once claimed to have the ability to bring in storms, and the sight of one was said to mean that a storm was imminent.

The fish were often said to attack small boats, and were blamed for the occasional disappearance of fishermen. One old story tells of a boat that was pulled under the waves by a Takitaro as horrified villagers looked on. Takitaro were also believed to snatch deer and other animals from the lakeshore. There is one account that describes a Takitaro carcass washed up on shore that when cut open revealed the remains of a deer.

Residents of the area have claimed to even catch Takitaro on occasion and in fact the fish are widely said to be good eating. A modern report of such a catch occurred in 1917, when workers investigating a floodgate managed to capture a fish that measured 150 cm (5 feet) long and weighed 40 kg (88lbs.). The men reportedly ate the fish, and described its meat as being quite good. Other specimens have reportedly been captured throughout the 20th century as well. Several of these captured specimens have been described as being anywhere from 160 cm (5.3 feet) to 2 meters (6.5 feet) long.

Stories abound of fishermen encountering these monstrous fish right up to the modern day, with accounts of mysteriously mangled nets and fishing poles violently yanked or broken by something very large and strong. One report spoke of something that looked like a “moving log” that was witnessed to bowl right through a fishing net. According to the eyewitness, the fish was almost 2 meters long and had what appeared to be a thick layer of fat.

While locals have been aware of these mysterious fish for a long time, perhaps the sighting that single handedly brought the Takitaro into the limelight and to mainstream consciousness in Japan was made by four mountain climbers in 1982. Tomoya Sawa, Kenzo Matsuda, I. Onodera, and Masakazu Sato, were hiking along Otori-ike’s nearby Nao Ridge when they saw something in the lake they could not explain. They noticed several huge fish estimated as being 2 meters (6.5 feet) to 3 meters (10 feet) long languidly swimming through the lake’s crystal clear water in a counter-clockwise circular arc. The group observed the fish in fascination for some time before the creatures sunk out of sight. The sighting conditions were perfect, with good weather and glassy, smooth water conditions.

This sighting was a sensation all over Japan, and was plastered over most major newspapers. The tale of giant fish dwelling in this picturesque mountain lake fired up the public imagination. Only adding to this fervor was footage captured by a group of TV reporters investigating Otori-ike in October 1983 in the wake of this sighting. The reporters’ footage shows three huge shapes swimming under the surface of the water.

In response to the incredible amount of attention this sighting and the subsequent footage generated, a scientific expedition was mounted to the lake in 1985 in the hopes of obtaining evidence of Takitaro. Scientists conducted a thorough search of the lake using sonar equipment, during which they made some peculiar finds. In the deeper parts of the lake, sonar picked up readings at a depth of 30 to 40 meters (98.5 to 131 feet) of what appeared to be fish much larger than any known to inhabit the area. Although the exact type of fish could not be determined, these sonar images seemed to confirm that something very large and mysterious was indeed lurking in the depths.

Gill nets laid out by the team also brought up some curious findings. The nets captured several fish that measured 70 cm (2.3 feet) long. While this is not a particularly large size when compared to the 2 to 3 meter lengths reported in most Takitaro cases, the mystery deepened when an ichthyologist identified the fish as being Dolly Varden trout (Salvelinus malma malma). This finding is puzzling for two reasons. First of all is that Dolly Varden are represented in Japan by a landlocked subspecies that only inhabit the northern island of Hokkaido. They were not previously known to be in Otori-ike at all. Second, Dolly Varden typically reach sizes of up to 61 cm (24 inches) for migratory individuals and 46cm (18 inches) for non-migratory ones, which would make 70cm (27.5 inches) uncommonly large for a landlocked trout of this variety. Whether or not these super sized Dolly Varden were connected in any way to the giant Takitaro, they nevertheless represent an unusual finding in their own right.

Although these Dolly Varden were indeed very large individuals for their species, no fish known to be present in Otori-ike are known to get as large as what is typically described in Takitaro reports. So what is going on in Otori-ike? What could the Takitaro possibly be?

The capture of exceptionally large Dolly Varden specimens in the lake has led to speculation that some species of fish in the lake could be exhibiting a form of gigantism. The reasoning behind this hypothesis is that isolated populations of fish could develop what is essentially insular, or island, gigantism. Otori-ike is not connected to any solid inflowing or out-flowing waterways, with the main run up being the Ara river, which is dammed. In terms of biogeography, a pond or geographically isolated lake like Otori-ike is considered an island in that it matches the general definition of “island” as an isolated ecosystem surrounded by unlike ecosystems. In the case of insular gigantism, some organisms are found to become much larger in island environments, and the same conditions can apply to lakes as well.

With fish, we can see this trend for instance in nine-spined sticklebacks (Pungitius pungitius). Studies have shown that landlocked populations of this species present in small, isolated ponds display significant increases in growth rate, extended longevity, and larger overall size compared to populations found in larger lake or marine habitats. This increase in size is particularly pronounced in the absence of any natural predators.

This type of gigantism is hypothesized to be caused by a relaxation of constraints such as predation and interspecific competition in the island environment. This in turn can lead smaller organisms to evolve towards an “optimal” body size in response to this overly simplified ecosystem, thus allowing for an increase in physical size and lifespan in comparison to individuals inhabiting an environment with such constraints in place. However, these increased characteristics fall dramatically once these factors are imposed.

This presents a problem when considering insular gigantism as an explanation for Takitaro. Otori-ike in fact does have a good amount of competitors and predators inhabiting its waters. The cold mountain lake yields a high oxygen content that is very suitable for predatory, cold water salmonoid fishes such as salmon and trout. Otori-ike is home to natural populations of cherry salmon, and it is also heavily populated by introduced species such as brook trout, which were stocked by the tens of thousands in 1898 during the Taisho era, and rainbow trout that have been intermittently stocked in the lake as well. Considering that insular gigantism is much less likely to be seen in the presence of such predatory and competitive pressures, it seems unlikely that any of these fish species would be particularly inclined towards developing gigantism in this particular habitat. Thus, perhaps it is better to look elsewhere for explanations for the large sizes reported with the mysterious Takitaro.

Another possibility is that we are dealing with some type of fish found in Japan that has somehow exceeded its known range, such as the aforementioned Dolly Varden. While this particular type of trout is not known to achieve anywhere near Takitaro proportions, there is another type of fish in Japan that can get large enough to perhaps account for the reports.

The largest known freshwater fish found in Japan is the Sakhalin taimen (Hucho perryi), also known in Japan as the Japanese huchen, Ito, and stringfish, which are found in Russia and the northernmost Japanese island of Hokkaido. These are some of the longest living and largest salmonoids in the world, living up to 40 years and with the world record size being 210cm (7 feet) long and weighing 110 lbs, 4 oz. Interestingly, the size of taimen have led them to become entrenched in folklore and mystery in other parts of Asia. For instance it is said that giant taimen inhabit China’s Lake Kanasi, with some reports putting them at sizes of over 3 tons. A Mongolian legend also tells of a huge taimen trapped in river ice that was gradually eaten by starving herders until the ice melted and it swam away.

Could a monstrous Sakhalin taimen be behind Takitaro reports as well? The main problem we face here is that in Japan these fish are only known to be present in northern Hokkaido, not the island of Honshu where Yamagata and its Otori-ike are. If taimen are indeed in Otori-ike, then they are either remnant, wayward populations that happened to become trapped in the lake when it formed, or they were intentionally placed there by someone. Considering that with the Dolly Varden there has been at least one species found in Otori-ike that should not be there, it is worth thinking about.

The prospect of intentionally introduced species leads us to other possibilities as well. Perhaps we even need to look at other types of exotic fish from places outside of Japan.

One possible culprit is a type of fish known as the snakehead, with two large species in particular, the Northern snakehead (Channa argus) and giant snakehead (Channa micropeltes), being the primary suspects. These fish, which get their name from their reptilian looking head and snakelike patterns on their body, are native to Asia in parts of China, far eastern Russia, and the Korean peninsula. They are long and slender fish, reaching up to 5 feet in length, and possibly more. Snakeheads are popular as a food fish in their native range, and are actively farmed for their meat. In some places, they were intentionally introduced into lakes or rivers as a potential food source, and were in fact introduced to Japan in the early 20th century for this very purpose.

Snakeheads are perhaps best known as a tenacious, persistent invasive species in many parts of the world where they have been introduced. They are known to be adaptable, voracious predators, and able to quickly overrun natural ecosystems. Any snakeheads in Otori-ike would not even necessarily have had to been dumped directly into the lake. These fish possess an unusual adaptation in the form of sacs that function something like lungs. These sacs can either be used to provide oxygen as the fish swims, or even allow it to survive out of water. Indeed, snakeheads are known to actually wiggle and squirm overland to new habitats and can survive out of water for a couple of days as long as they don’t dry out. Due to this feature, snakeheads could have found their way up dammed waterways and just “walked” over to Otori-ike.

Snakeheads are present in Japan and their size and odd appearance could perhaps be the source of Takitaro reports. However, it is unclear whether this tropical fish could survive in such cold, high altitude waters no matter how adaptable it is.

Other fish from outside of Japan could also be behind Takitaro sightings as well. The most commonly proposed are sturgeon or alligator gar, released into the lake for the purposes of eating or sport-fishing. Unlike the land traversing snakeheads, these species would have to have been directly introduced into the lake for them to be present there. It doesn’t seem at the outset too far-fetched considering that brook trout and rainbow trout were extensively introduced to the lake as food fish and for sport, and this has also happened on a smaller scale in lakes throughout Japan with unscrupulous anglers secretly releasing black bass.

Some exotic species of fish that get very large are also widely available in the pet trade in Japan. One very large fish available to aquarists for purchase is the pirarucu of South America. These fish can get enormous, in excess of 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) and over 100 kg (220 lbs). Many people who buy them are not prepared for just how incredibly big these fish can actually get. This could lead to a scenario where we have surprised aquarium owners releasing fish that they are no longer willing or able to take care of.

Perhaps the biggest challenge we face when using introduced exotic species as an explanation for Takitaro sightings is the relative remoteness of Otori-ike and the difficulty of accessing it. The nearest road is 8 km (5 miles) away through rough, mountainous terrain. To reach the lake requires at least a 3 hour, demanding hike, and once there, even more work to get down the steep surroundings to the shore. This seems like it would be an awful lot of trouble for someone to go through just to release a few fish into the lake. With brook trout and rainbow trout, there was a funded, organized program focused on putting a large amount of fish there. However one wonders if a only one or a few people with no such logistic support would go through the trouble and resources of trekking out into the mountains with live fish in order to secretly dump them in Otori-ike.

As with the snakeheads, it is also unlikely that tropical fish such as pirarucu would be able to survive for any appreciable length of time is this cold mountain environment. Many of the larger aquarium species are simply not compatible with this sort of freezing, high altitude habitat, and would likely die in short order.

Images of various candidates for possible explanations are, from top to bottom:

1) Sakhalin taimen,

2) snakehead (this one is a Northern snakehead),

3) alligator gar,

4) pirarucu, and

5) sturgeon (shown below).

Another question it seems worth asking is if the Takitaro is perhaps something that has always been there. One avenue of inquiry is that perhaps the fish are a relic population of an ancient, extinct species, or even an unknown fish species that was trapped when the landslide formed Otori-ike from a stream long ago. Indeed Takitaro have been sighted in the lake since the beginning of historic human settlement in the area, which is namely concentrated in nearby Asahi village. If sightings have been consistent for so long, this leads credence to the idea of some large fish species became isolated in the lake during its formation in ancient times.

Pumped up super fish, out of place species, exotics, ancient giant fish, or just plain unknown; whatever they are, Takitaro have achieved a somewhat legendary status in Japan. Indeed even to this day, many a fisherman has thrown their line into the clear waters of Otori-ike wary of any large shadows lurking under the surface and anticipating the possibility that they may receive a mighty tug from this colossus of the depths.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Love these “in depth” fish tales, Mystery Man. I’m no fisherman myself but nothing like a mystery to provoke me into considering a hook and line survey someday should I find myself in the Land of the Rising Sun. Otore-ike is in just the kind of alpine terraine I like best and I’ll add it to my list of “places to see” if I ever get to Japan and don’t become inextricably wound up in the rest of the dizzying and breathtaking array of cultural attractants of the kind that Japan specializes in like no place else.

I hear that these days,,thanks to advances in molecular biology, water from lakes and streams can be tested for specific species whose DNA would be diffused through the system. I guess that could narrow the possibilities of known species, though the the mystery of the unknown and the question of gigantism due to environmental will no doubt provide plenty of fodder for future fishermen stories.

In the mean time, you mentioned the nearby town of Asahi…makes me thirsty, for a Kokanee, appropriately. Cheers.

One possibility is a large catfish from the Bagarius genus that includes the Goonch, many of these are still present in SE Asia. But I will admit, the drawing though looks more like an older salmon. Based on the temperatures, this is a reasonable guess.

Great post. As always, Mystery_Man. You’ve done yourself proud. 🙂

Cryptidsrus, Dogu4- Thank you, kind sirs. Always good to have someone enjoy my work.

Dogu4, if you are still here- I too am very interested in this type of terrain, but what really attracts me to cases like this is how it ties into my fascination with the ecosystems of islands and isolated lakes like Otori-ike. There really are a lot of unique evolutionary paths to be found in places like this.

I’ve also heard of that method of testing water for DNA that you mentioned, but it seems that this technique is not precise enough just yet for it to be really reliable on a large scale. First you have so many factors to consider here, like any inflow or outflow no matter how meager, as well as currents and the effects of differing oxygen contents on possible results, in addition to the degredation of potential DNA samples due to any pollutants in the water source.

On top of that there is the high possibility of contamination, which would skew accurate results. It is well known just how easy it is to contaminate DNA samples with the introduction of foreign DNA, a good sample can be ruined or at least rendered inconclusive just from improper handling. That is likely going to cause problems when you have the presence of DNA of so many species all mingled together, not to mention the DNA of fish and amphibian species from outside of the lake coming in through in-flows, as well as from any terrestrial animals that could be washed into the lake by rain or other means. Also, like I said, there are a lot of opportunities for degredation of the DNA due to environmental conditions and any pollutants or chemicals that may be present.

When testing DNA against known species, it might prove helpful to a degree, but perhaps not for demonstrating proof of an unknown species.

It seems to me that this method would likely be too time consuming and not accurate enough for the purpose of tracking down an unknown. This method is most certainly not something like plugging a sample of water into a computer and having it give you a nice, pretty print out of every fish or amphibian species in the lake. It would work better if we knew exactly what we were looking for in the water sample and specifically looking for the presence of that.

The technology may progress to the point where it is a solid option in these cases, but unfortunately as it stands it just doesn’t seem practical enough just yet in my opinion. For now, the most reliable way is probably the old fashioned one, by going out and finding soild DNA samples to test.

Anyway, thanks for the thoughtful comment as usual.

Thanks for the insight regarding DNA sampling in context of natural bodies of water. I’m sure you’re right about the present state of technology so in the mean time we’ll just have to do it the old fashioned way; a submarine brought up with a chopper. Anyone from Monster Quest out there?

I’ve seen these big fishies myself about 15 years ago when I went to Japan for the Wonder Festival, quite impressive and they looked a lot like salmon. They ranged between 7-8 feet long. Sadly I didn’t see Ishi though.

Interesting indeed. Thanks MM!

The lake is landlocked, but I am wondering also about food sources. Obviously, if there are no natural predators for these big fish (maybe other than each other), then there would be no stopping them. And there’s no telling how old the things are, but there must be a steady food supply to support such a higher predator–so my question–are there still streams that feed into it, or is it completely cut off from other water sources, thereby limiting the food to what is in the lake and replenishing itself naturally?

As to the identity, I think all your possibilities are sound, including some unknown species. It also seems that the lake is small enough so that we’re not dealing with some monstrous body of water like NEss or CHamplain. Therefore, under than the ability to get to the lake itself, it should be relatively easy to set up a lookout area and cover most of the surface…and if you can get a boat there (maybe bigger than a canoe considering the folklore:), you could do some depth finding.

I know–sounds easy in a blog doesn’t it…if I could get there, I’d help!:)

Still, this particular place sounds like a great microcosm for trying to hunt down a water going cryptid!

Thanks again–I’m always eager to hear about stuff coming from Japan…it’s got a long rich history and folklore, and I personally don’t get a lot coming out of there unless I go looking for it in depth, or have a contact like you. 🙂

SHJ- As far as I know, this lake is completely isolated. Most of the inflowing water comes from rain and snow run-off. The Ara River is the only real waterway that leads up to the lake and it is completely dammed off.

So yes, this is an isolated ecosystem. I believe there are good food resources there, however. There are self sustaining populations of smaller fish in the lake, and of course the predatory fish such as the trout and salmon are going to feed off of each other as well.

The thing is that this sort of fierce competition is going to most probably limit the size of the fish here. You may get a few that reach a ripe old age and get sort of a grand daddy fish out there, but the Takitaro sizes are far larger than any sort of fish known to be there.

Anyway, there is plenty to eat there for fish as big as these things are reported to get.

I think you are right in that we have here a good opportunity here in this relatively small lake, or “microcosm” as you put it so well. There is less area to cover and therefore a better chance of maybe finding something.

Sadly, I’ve never been to this particular lake, but if I had the time and resources, I might just try it myself. 😉 Maybe if I had help. If you’re ever in Japan and need a hand, you know who to ask.

Thanks for the kind words about the article. I truly am committed to providing good English language overviews to these cryptids. There is surprisingly little in English available on these creatures, so I hope I am providing something useful here.

Korollocke- Wow, that sounds amazing. In all of the time I’ve been investigating Japanese cryptids, I’ve never actually seen one.

By the way, I’ve been to lake Ikeda. I didn’t see Ishii either.

Very interesting article. I have to say at first that you are surely right to doubt that exotic species like snakeheads or even arapaimas could survive there, this fish are are hardly able to survive in the cold waters of the northern parts of Honshu.

To come to the reasons why some species show “gigantism” there is a lot to say. Sticklebacks are probably not the best comparison, as they are very small fish. There were experiments with guppies which were released in predator-free habitats, and they have shown an enormously fast evolutionary size-increase, i.e. they did not just grew larger because they had good environmental conditions and lived longer, but because they really evolved to larger size. This fish without pressure by predators showed similarities to the sticklebacks you mentioned. They grew larger, lived longer and had comparably few offspring, furthermore they reached sexual maturity at a later stage than their introduced ancestors some years ago. But as already mentioned, sticklebacks and also guppies are not a good reference in this case. Such small fish have incredibly much predators to fear, even some invertebrates. Larger species have in general much lesser predators, and only subadults have to fear predation by other species or larger relatives.

In bigger fish the opposite of the situation of sticklebacks can happen. It is known for several species that landlocked populations have smaller average sizes than their anadromous or saltwater relatives. Some salmonids show a highly variable morphology dependent from their habitat. Brown trouts (the only native trouts in most parts of Europe, rainbow trouts were introduced since the late 19th century too at many regions) for example grow sometimes not larger than 20 cm in waters with little food and also already reach sexual maturity at this small size. When they migrate to the sea they get a silvern colour and can reach lengths of well over 1 m and look very similar to atlantic salmons (Salmo salar). When they inhabit big and deep lakes they grow to lake trouts, which are also of a different phenotype. They are big and often very stocky with large heads and big jaws. The size is mainly dependent on the availability of food, which is in general just larger in big lakes and in the sea than in small rivers or creeks. Lake trouts grow also sometimes quite big but are (at least at Salmo trutta) exceeded by their anadromous cousins which live most of their lives in the sea. Theoretically it could be that a large growing population of salmonids like big trouts inhabits the lake. If the alleged sizes are true, there would probably be a combination of evolution towards big size and good food supply. On the other hand the lake is not that big at all, so it seems a bit strange.

A completely other possible identification would be a member of the Silurus genus. Several of them occur in japanese waters (it seems that the highly geographical isolation of the japanese islands it responsible for this, given the fact that in whole Europe up to parts of Asia only one single and geographically highly located species, Silurus aristoteles, occurs besides the wide-spread wels catfish Silurus glanis), for example Silurus asotus which is also present at Honshu. They look very similar to Silurus glanis, but have several differences. They have a different number of fin rays for example, furthermore they posses only two mandibular barbels, in contrast to four in Silurus glanis, and have a slightly different body shape and colour. They also stay much smaller, the maximum published size for Silurus asotus I found was only 1,30 m, in contrast to a confirmed maximum length of 2,78 m in Silurus glanis. But some of the japanese species seems to grow larger and could be possibly responsible for sightings of 1,5 m – 2m long fish sightings.

Sordes- Sticklebacks are indeed probably not the best example, but I just used them to illustrate the concept of island gigantism and how this can apply to lakes as well as the traditional image everyone has of islands as land surrounded by water. I wanted to establish some sort of well studied precedent for this in freshwater fish and that is what I came up with in this case. But my example also shows that lack of constraints would need to be present even for these guppies to get larger, which is not the case in this lake. So my point was that considering the conditions that need to be in place for insular gigantism to occur even in sticklebacks, it is unlikely it is happening in this particular lake with any fish.

As I mentioned in the article, I too think gigantism is not a good possibility here, which is what I was trying to convey with that example. With the predatory salmonoid fishes, I would expect that they would in fact be more likely to even be smaller due to the incredible amount of interspecific competition that appears to be present in this lake, which of course would have an impact on food availability.

To balance out the whole insular gigantism argument, it is also important to remember the concept of insular dwarfism, which is what will happen when more rather than fewer restrictions on food supply and competitive pressures occur in the island habitat. Often larger animals, especially predators, will become smaller over time under these conditions. In this case, predatory animals often exhibit dwarfism rather than gigantism. So this has bearing when considering the possibilities. The lake in question does not display the lack of pressures that would be likely present in order for even guppies to display gigantism, so giant salmonoids indeed seem unlikely.

One thing, though is that many of the competitors were introduced here by humans well after geological formation of this lake. Perhaps something native to the lake had evolved to be larger somehow long before the addition of these new factors.

Sordes- I also must reiterate that my stickleback example was also meant to show the types of evolutionary factors (and food availability is one, affected by competition) typically seen in cases of insular gigantism and the constraints that would limit this. In the case of this lake, none of of these factors are really in place, and in fact there are challenges that would limit the development of gigantism in any species. The small size of this lake, the competition, and the amount of predators feeding on each other would make gigantism seem an odd thing to find here.

The availability of food seems good in this lake to the best of my knowledge, but there is a lot of competition, which like in the case of sticklebacks, would limit any capacity for gigantism. I think it would limit any sort of large growth overall.

I think the only reason gigantism has ever really been brought up at all in relation to the Takitaro is because of the uncommonly large Dolly Varden that were caught in the lake. It has been one possibility brought up, however I really do think an unlikely one.

But you are right with regards to food availability. This is certainly a factor determining growth, and has an effect on size even when it is not necessarily an evolutionary trait that has established itself in the species at any genetic level.

Evolutionary trends or not, I don’t see much that leads me to beleive that we would have super sized specimens of any given species in this environment.

Anyway, thanks for the input and I am pleased you liked my article.

In some cold lakes with several species and/or subspecies of salmonids it happens that single lines of a species or a subspecies become especially large by preying on the other salmonids. This is known for trouts for example. Becoming the top-dog of a lake can lead to large body-size by eating competition away. But this would hardly explan such size than the alleged dimensions of the takitaro.

Sordes- You raise a lot of valid points to be sure. I agree that this environment is not particularly conducive to such large sizes. We are talking about fich here that are well outside the known dimensions for any fish species documented in the lake.

If these fish are indeed real, and indeed as large as is reported, then something is going on. I think we have both established that gigantism is not likely. And the habitat seems like it is too small and populated by predatory salmonoids to offer a really robust food sources that could account for large sizes. Even if there were such food resources, I’m not sure that can explain the enormous sizes beyond what is currently known for these species.

I tend to think that we are dealing with a species not known to be in the lake, such as Sakhalin taimen, an unknown, or even your proposed Silurus.

Such large fish in this environment would certainly be odd, and not what I would expect to find here.

Thanks for joining the discussion and adding your insights.

Always enjoy these discussions as I learn a lot from them. It seems to me that the size of fish is related usually to 3 things: the genetics of the fish, the amount of food and the size of the habitat. But there is something about lakes, however, that always make me wonder because of their special qualities like the limited diversity and respective niches that can become available to lake fish in which unique aspects of radiative adpatation might come into play, and also the fact that lakes, particularly mountain lakes, can form in drainages that themselves are commonly coincident with fault lines and therefore can have chemistry that differentiate one from another. I wonder if chemistry might not have some epigenetic effect on some species as the genetic control isn’t necessarily a simple “on or off” switch for the trait of gigantism, but the degree to which the growth genes are expressed which in turn could be effected by local conditions of temp and signal chemicals.

Of course, making a scenario more complex is a good way to make specualtion even more vague and science likes to try to pin things down and eliminate unlikely possibilities..but then, I’m not a scientist and love to ponder the near infinite possibilities that seem to exist, which is why I come here and enjoy it so much.

cheers.

Dogu4- Well, those factors of size are the simple way of putting it, however it is a lot more complicated than that as there are other variables intrinsically linked to these and they all interconnected to some degree.

For instance other factors to consider are predation, amount of geographic isolation, and the level of competition present in the habitat, and these all have an effect on each other to some extent. Food availability can influence genetics, habitat size effects food availability and predatory pressures, and so on. For example in the case of competition, this can have an effect of the food availability, which over time could be expressed at a genetic level (such as gigantism and other adaptations) due to evolving traits to deal with these pressures.

The size of the habitat can have an impact on all of these things. Where these factors are all present in large habitats as well, they are more profoundly expressed in a smaller one such as an island or lake. Each of these variables is simply more acutely felt in a smaller habitat. You can imagine it like throwing a stone in a lake. If you throw it in a large lake, the ripples are not so significant whereas in a small pond they are more profound. The same goes for changing variables within a confined ecosystem such as a lake or island.

This is why you can see curious evolutionary strategies such as gigantism, dwarfism, and others depending on the specific pressures present. The factors you mention are having a more significant and immediate effect on the organisms inhabiting these smaller habitats.

In terms of evolution, the limited size of the habitat can cause the change in balance of these factors such as food availability and so on to favor certain radical evolutionary steps, such as the insular gigantism and dwarfism that I mentioned. It can create a situation where you have a more pronounced evolutionary “arms race” so to speak.

On top of this, there is even more to think about than just size in island ecosystem. The degree of geographic isolation of islands and lakes also means that you have this all going on in seclusion.

The combination of all of these things can lead to some pretty interesting adaptations in species compared to their continental relatives. In islands and isolated lakes we can find a good amount of unique, endemic species, all shaped by the unique circumstances and increased (or decreased) pressures directly related to their limited habitat size.

I think islands and lakes like this present a great microcosm for studying the effects of these evolutionary pressures and how animals adapt to them.

I would agree that islands and lakes are places where we can often find unusual evolutionary strategies and interaction of ecological variables. In the case of Otori-ike, perhaps there is something going on that we are unaware of, some factor that we have not even considered yet.

It’s interesting to think about.

Dogu4- I also wanted to add something in addition to the unique ecological dynamics of food resources, competition, predation, habitat size, isolation found in island habitats.

I think another factor that we could be dealing with here is the oxygen level in the lake, which is to some extent linked to the temperatures present. Otori-ike has cold, highly oxygenated water, which can infer an advantage in organisms by providing them with plentiful energy reserves. This may also have an effect on size in the lake in conjunction with the food availability and other factors.

As I mentioned, these variables don’t exist in a void, they are all tied together, and perhaps made more “simplified” and acute by limitations of the smaller habitat. Rather than looking at just one factor when addressing the size of Takitaro, I prefer to look at the overall picture, and the way all of these dynamics are interacting to perhaps produce what is being reported in this locale. The interplay between these things in somewhat limited island and likewise lake ecosystems is what really draws me to cases like the Takitaro, and indeed island wildlife in general (which is where most of my professional interest is.)

Anyway, yes there are many unique possibilities for a remote, isolated environment such as this. For now, I am more or less trying to look at how these pressures and constraints we’ve been discussing, or lack thereof, are interacting within this isolated lake in the context of the known species and their apparent population densities.

Still, I agree there is room for the hypothesizing of other factors such as oxygen content and chemical make-up of the water. I greatly enjoy speculative biology, so you’re not going to get much argument from me there.

Who knows, maybe some unique, currently undescribed or little understood process could be uncovered at work in this particular lake. Stranger things have happened.

I lived in Asahimura for a few years and I also know Masakazu Sato who reported the fish in the 80’s. He was the mayor for quite some time and still lives in Ootori near the lake and still hunts and fishes there as well. He has some photos in his house that he says are of Takitaro as well. A very friendly man, he’ll talk your ears off if you let him (all in Japanese of course). He owns a guest house in Ootori, the last tiny village before you start up the gravel road towards Ootori Ike. You can stay there for very cheap and have a chance to talk to him about it. Also, ask him about Kappa while your at it.

I’ve been to the lake on many occasions but sadly have never seen Takitaro. It’s a very difficult lake to get to even hiking. I live in Colorado now and hiking the mountains of Japan was much more difficult due to the steepness, foliage, and wet weather. Asahi is a very rural area and the only road that leads up to the lake is very narrow and long passing through many old villages and tunnels. It’s beautiful. A true wilderness in Japan.

There are so many tales of the fish sighting, ghosts, and other creatures up there and the area is so remote, I wouldn’t doubt any of them. I still have many friends in Asahi and go back whenever I get the chance. It’s by far my favorite place in Japan.