February 14, 2009

Bradypus pygmaeus is a pygmy three-toed sloth discovered in 2001 on a tiny Panamanian island, where it dwells in mangrove forests. Photo: Bill Haycher

Mirza zaza, also called the northern giant mouse lemur, was discovered in Madagascar in 2005. Photo: David Haring / Duke Lemur Center

Two photos of the grey-faced sengi, Rhynchocyon udzungwensis, a giant elephant-shrew, was first filmed in 2005, and confirmed in 2006. Photo: Francesco Rovero.

The news was announced in 2006 of the discovery of the new giant peccary, Pecari maximus, in Brazil’s River Aripuana basin.

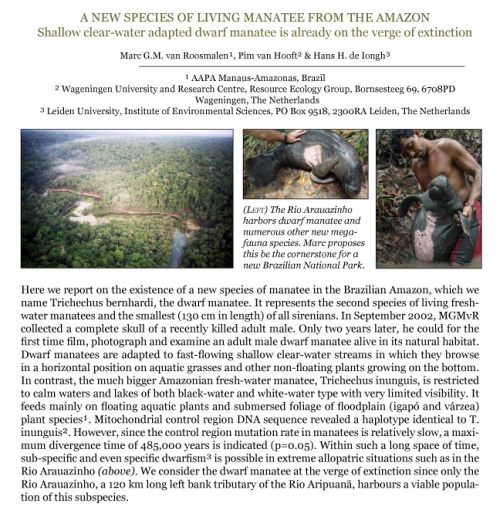

In 2007, a new dwarf manatee (Trichechus bernhardi) was discovered in South America.

Some people see a dark cloud over any good news, and anyone who has read Paul Ehrlich for any length of time knows of his negative spin on most biological and animal news. For me, I tend to think that having some admission that, indeed, 408 new mammals ~ not just new animals, but mammals ~ have actually been discovered is cause for some celebration.

The new study’s authors, Ehrlich and Gerardo Ceballos found that of the 408 “new” species, 221 have restricted distribution, while 23 are already likely at risk of extinction. Forty percent of the species are large and distinctive, the balance are “cryptic” (interesting choice of words). Many of the discoveries have occurred in areas that are not considered “biodiversity hotspots.”

Nevertheless, to be fair and hear his side, here is the Ehrlich view:

Discovering mammals cause for worry

BY Louis BergeronIn the era of global warming, when many scientists say we are experiencing a human-caused mass extinction to rival the one that killed off the dinosaurs, one might think that the discovery of a host of new species would be cause for joy. Not entirely so, says Paul Ehrlich, co-author of an analysis of the 408 new mammalian species discovered since 1993.

“What this paper really talks about is how little we actually know about our natural capital and how little we know about the services that flow from it,” said Paul Ehrlich, the Bing Professor of Population Studies at Stanford.

“I think what most people miss is that the human economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the economy of nature, which supplies us from our natural capital a steady flow of income that we can’t do without,” Ehrlich said. “And that income is in the form of what are called ‘ecosystem services’—keeping carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, supplying fresh water, preventing floods, protecting our crops from pests and pollinating many of them, recycling the nutrients that are essential to agriculture and forestry, and on and on.”

Ehrlich conducted the analysis with Gerardo Ceballos, a professor of biology at the National University of Mexico. They are co-authors of a paper describing the work, scheduled to be published Monday, Feb. 9, in the online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The 408 newly discovered species amount to approximately 10 percent of the known species of mammals. As a group, mammals have been very well studied, Ehrlich said, and their size makes them relatively easy to spot compared to insects or microbes. It is not that surprising that multitudes of new insect species are still being discovered, or that new extremophile species are found in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, he said. But the new mammals include a small antelope weighing approximately 200 pounds and surprisingly high numbers of primates, more than would be expected if the discoveries were randomly distributed across higher taxonomic groups.

“Our analysis indicates how much more varied biodiversity is than we thought and how much bigger our conservation problems are if we’re going to maintain the life-support services that we need from biodiversity,” Ehrlich said.

Among those ecosystem services is disease control.

“There’s an important set of diseases called hantaviruses that infects human beings and quite frequently kills them. And it turns out that if you reduce the diversity of the different species of rodents, say, in a forest, the rodents that carry hantaviruses can become more common. And the results for human beings are more death and disease,” Ehrlich said. “So by reducing the diversity of mouse-like creatures in a forest, you can make that forest more dangerous for people.”

Many of the newly discovered species have small populations or limited geographic ranges, making them particularly vulnerable to extinction.

“The rarer of the species and the smaller of the populations often disappear without us even knowing that they are going,” Ehrlich said.

Although not every species that goes extinct plays a crucial role in controlling diseases like hantaviruses, that doesn’t necessarily mean we can do without them.

Ehrlich said the answer to the question, “What difference does it make if we put a strip mall in here and this little fly goes extinct, or this little mouse goes extinct?” lies in the rivet-popper hypothesis, which he and his wife and colleague, Anne Ehrlich, a senior research scientist in the Department of Biology at Stanford, developed in the 1980s.

An airplane wing has a certain amount of redundancy in its design, as does much of nature. So you can pop off some of the rivets and the wing will still hold together and the plane will still fly. But at some point, you’ll have removed one too many rivets and the plane will crash.

“Even though you don’t know the value of each rivet, you know it’s nuttier than hell to keep removing them,” Ehrlich said. “There is some redundancy, but we don’t know how much. And facing serious climate disruption, humanity is going to need more redundancy in the little rivets, the species and populations that run the world.

“We are facing for the first time the collapse of a global civilization,” he said. “You have to reduce the scale of the human enterprise to having a chance at preventing that.”

Ehrlich said that continually creating more mouths to feed will only chew up more of Earth’s natural capital.

“The economy of nature is what allows us to have a human economy. If we let the infrastructure of nature go down the drain, then we just can’t make up for it with human infrastructure,” he added. “It just can’t be done.”

Stanford Report, February 9, 2009

Forgive me, but while I agree with the need to save non-human biodiversity, and while Ehrlich’s constant call for population control is well-known, appreciated, and acknowledged, enough is enough. Now pushing the media buttons regarding the coming “collapse of a global civilization” seems to merely be an alarmist yelling in a crowded theater for sensationalistic headlines.

Frankly, I’d rather hear about 408 new species discoveries of mammals in the last 15 years (a rather small window of time, actually) than none!

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, New Species