December 9, 2009

“Why haven’t we found a Bigfoot body?” is one of the most frequently asked questions I get in the museum and at the end of my lectures on the road. I answered it partially, in the last chapter of Bigfoot! The True Story of Apes in America. Let me share part of what I discuss with those interested in the longer answer.

If animal remains were so easy to find, the forests of Maine would be so filled with moose and deer antlers each year from those dropped by the thousands of animals shedding their pairs, hunters and hikers would not be able to move around without tripping over mountains of discarded antlers. But every year, we are greeted by mostly fresh ground upon which to stroll.

Other than road kill, would not bear carcasses litter the woods of any country where they are found, and won’t dead mountain lions occasionally be found within some forest of the North American West? But despite numbers that must surely outnumber the Bigfoot population, decaying bears and pumas do not dot the landscape. Instead, nature finds a way to keep the forest floor clear of rotting remains with everything from flies to ravens/crows, coyotes to turkey/black vultures, bacteria to other microbes, all doing their work.

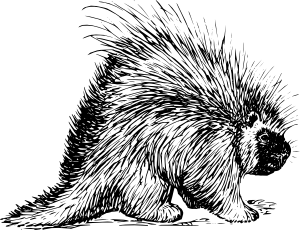

As to the example of those antlers and any remaining bones, well, besides mice, voles, and rats, I have one significant candidate for everyone to consider when dealing in the speculation about finding those extremely rare Bigfoot bones: porcupines. Porcupines will eat away whole racks of antlers and most of the bones of any animal.

The 27 species of porcupine worldwide like to gnaw on antlers and bones for the calcium and other minerals, appear to also eat bones to sharpen their teeth and seem initially attracted to bones and antlers by the odor of urine and their salt content.

But could these animals which may be the often overlooked reason for why so few bones are found in the woods also be the source of an eventual find of the century?

Porcupines, both Old and New World species, and other animals (hedgehogs and echidnas) that all look and behavior similarly due to convergent evolution, have interesting habits that should be studied by Sasquatch researchers.

One important behavior of some species of porcupines is that they hoard bones of other animals in or around their dens. Porcupines sometimes are found with bones in their living spaces. For example, the North African crested porcupine (Hystrix cristata) and the Cape porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis) of sub-Saharan Africa, especially in areas deficient in phosphorous, will practice osteophagia, or gnawing on bones. These porcupines will often accumulate large piles of bones in their dens.

In Africa, researchers have found that porcupines are opportunists, and use both brown and spotted hyena dens that have naturally leftover bones in them. Also gathering bones themselves, certain African porcupines have been found to typically collect only degreased and defatted bones.

In North America, studies of situations in which bones accumulate today and in the past often include porcupine caves. For an intriguing article on what Pleistocene mammal remains were found in one such gathering of bones, see “Bears and Man at Porcupine Cave, Western Uinta Mountains, Utah” by Timothy H. Heaton, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, in Current Research in the Pleistocene, vol. 5, pp. 71-73 (1988).

The odds are more highly in favor of Bigfoot bones and bodies never being found than being found. But if they are ever found, might Bigfoot teeth or old bones possibly will be discovered near or in porcupine habitation sites.

We won’t know unless we look, and reexamine past and future “unidentified” finds from porcupine caves, digs, and dens.

661 Congress Street, Portland, Maine 04101.

For more museum information, see here, here and here.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Bigfoot, Cryptomundo Exclusive, CryptoZoo News, Forensic Science, Sasquatch