March 29, 2011

With all that is happening in Japan now, I would like to re-print an article (with some very minor additions) I wrote here awhile back for the reading pleasure of new Cryptomundians as well as a refresher for those who have been here awhile. This is the first part of a series, and I will be releasing Parts 2 and 3 over the next few days as well. Enjoy.

Japanese Wolves Part I – Honshu Wolf

by Brent Swancer

“From the land of the subcompact car, we present the subcompact wolf.” ~ Matt Bille

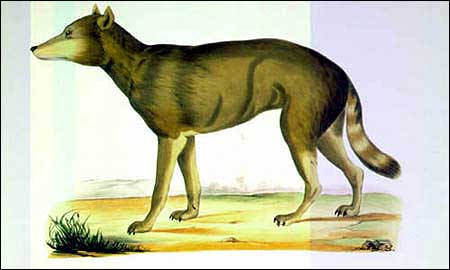

This description by cryptozoology writer Matt Bille is fitting. The commonly thought to be extinct Honshu wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax) was the world’s smallest wolf, standing just a little over a foot at the shoulder.

Also known as the Hondo wolf, the yamainu or “mountain dog,” and the corruption of this word, shamainu, the Honshu wolf did not particularly resemble the grey wolf that most people are familiar with. In addition to the petite size, their bodies were more compact and narrower, with short, wiry hair and a thin, dog-like tail that was rounded at the end almost as if it was bobbed. They were also more low slung, with legs that were shorter in relation to their body length.

The Honshu wolf was quite dog-like in appearance, and in some ways had characteristics that bore more resemblance to some other types of wild canids like jackals or coyotes, and to “pariah” dogs such as dingoes, than to its Siberian wolf ancestors.

Although the Honshu wolf is currently most commonly classified as a subspecies of gray wolf, this is open to some debate. There are those who argue that the physical differences present were enough to consider the Honshu wolf as its own species instead of merely a miniaturized grey wolf. For instance Japanese zoologist Yoshinori Imaizumi, former head of animal studies at the National Science Museum and widely recognized as the foremost expert on Japanese wolves, has long held that the Honshu wolf should be given species status. There are even some who have questioned whether the Honshu wolf was a true wolf at all.

The great diversity and plasticity of canids make it a bit unclear and tricky when it comes to precise taxonomical classification, so the matter is debatable. While the issue of the Honshu wolf’s taxonomical status may not be completely settled, whether a separate species or a subspecies, its story is a long and sad one.

The Honshu wolf was once a fairly common sight throughout its former range of the Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu islands of Japan. Residents of rural mountain farms and fields were well acquainted with the wolves, however the people’s reaction to them was not one of panic or fear. Far from being perceived as the evil or nefarious denizens of the forests that wolves were often depicted as in other parts of the world, the Honshu wolves were highly respected and even revered creatures.

The wolves were seen as mountain gods, and this divine nature can be seen in some other names for them such as magami meaning “true god,” and yama no kami , or “mountain god.” These wolves had a powerful image as benign protectors of the forest, which is mirrored in much of the folklore of rural areas concerning them.

This protective role can be seen in stories of the Okuri Ookami, or “Sending wolf” which tell of Honshu wolves keeping travelers from harm and guiding the way through the woods, ensuring their safe return home. The wolves were also thought to keep wild boar, deer, and other damaging pests away from crops, ensuring a good harvest.

Farmers thought of the wolves as generous benefactors in other ways as well, as the animals would on occasion leave parts of their kills behind, which the farmers would repay with offerings of their own. The wolves were sometimes even said to help the old, poor, and infirm, with stories in some traditions telling of them bestowing wealth or curing sickness.

Even in death the Honshu wolves retained their protective powers. Parts of their bodies such as skulls, pelts, and bones often hung up to ward off evil spirits, and in some cases treated as objects of worship. Even the Honshu wolf’s scientific name, Canis lupus hodophilax, which was assigned by Temminck in 1839, is indicative of its role as a protector. Hodo means “path” or “way” in Greek whereas philax means “guardian,” so we get something like “guardian of the way.”

The Japanese went through great lengths to show their respect and appreciation to these wolves. Offerings of food were set out for them to eat, prayers were said to them, and temples and shrines were constructed in their honor. To this day there are Shinto shrines devoted to the Honshu wolf in some areas of Japan. Although the wolves were occasionally hunted if they posed a threat, it was seen as bad luck to do so, and was said to invite divine retribution to anyone who did so.

The beginning of the end of the Honshu wolves is largely thought to have been heralded by a rabies epidemic that started in the mid to late 17th century and spread quickly through Japan. There were a large number of dead or sick wolves seen in the wilderness during this time, which is testament to the danger the disease posed. Rabies took a heavy toll on the wolf population of Japan, and had the further effect of negatively shifting people’s already changing perception of the wolves as well.

Modernization had already brought in new farming techniques and attitudes that did not leave much room for the wolves. New agricultural practices such as increased use of river valleys for farming rather than mountains meant less traditional reliance on the wolves for protecting crops. Increased livestock production also created new tensions between the wolves and the residents they were once seen as protecting.

Rabies only aggravated these already shifting attitudes. Not only were the wolves seen as vectors of the disease, the idea of rabid wolves descending from the mountains into their village sparked in people a growing, newfound fear of the wolves. It began to be seen as acceptable to hunt them, and farmers began to kill wolves when they could, the threat of spiritual retribution all but forgotten. The divine image that the Honshu wolf had held for so long began to crumble as fast as their numbers.

This became the age of the wolf hunts. During this time, large mobs of people from all levels of society took to the forests in an angry, bloodthirsty quest to slaughter as many wolves as they could find. It must have been quite a sight to see these chaotic, motley groups of hundreds of would be hunters, with farmers armed with whatever weapons they could find marching alongside samurai in a united cause to scour the forests for wolves to kill. These hunts became major events, and over time came to produce fewer and fewer kills until they became more excuses to gather together rather than any expectations to find any more remaining wolves to kill.

In the early 1900s, a zoologist by the name of Malcolm Anderson had come to Japan to collect exotic animal specimens. On January 23, 1905, some village men in Nara prefecture brought in the carcass of a Honshu wolf which they claimed to have shot two days earlier near a woodpile as it chased a deer. The men initially had thrown the carcass away but then had remembered the foreigner collecting specimens, and figured that they could fetch a price for it. They were correct. Anderson purchased the remains and sent them back to London along with the carcasses of other animals he had collected such as deer, boar, and Japanese serow. This Honshu wolf specimen was taxidermed and put on display in the Museum of Natural History in London where it remains to this day.

It was the last of its kind.

Or was it?

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we will look at the answer to this question and continue the story of the Honshu wolf.

About mystery_man

Filed under Cryptid Canids, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Mystery Man's Menagerie