April 16, 2012

© Loren Coleman 2012

“Ideas, like large rivers, never have just one source.” ~ Willy Ley

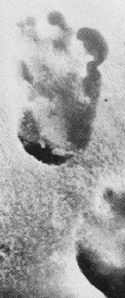

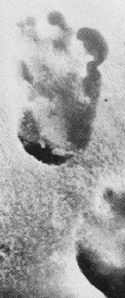

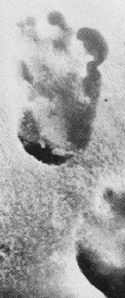

In Willy Ley’s chapter entitled “Abominable Snowman,” in his book Salamanders & Other Wonders (1955), the mid-century German-American romantic and exotic zoology commentator wrote of the 1951 expedition to Mt. Everest. Ley said of the remarkable find of Yeti footprints: “Eric Shipton, who had come across the tracks when they were still fresh, took a photograph which proves that, no matter how many ‘Yeti tracks’ were really made by bears, these were decidedly not. There is no mammal known to science in this area which leaves such tracks. And although they resemble human tracks they are as decidedly ‘unhuman.'”

The reality of the footprint finds caused a rush of reviews, reconstructions, and reactions, from casts of the print to stamps being printed.

In recent days, I have discussed the circumstances behind the photographing of the 1951 Eric Shipton-Michael Ward-Sen Tensing discovered Abominable Snowmen or Yeti footprints. In “A Short History of the Shipton Snowman Track Photographs and the Tchernezky Cast,” the role of zoological technician Wladimir Tschernezky, the first creator of a replica Shipton track cast, was detailed. Furthermore, in that examination and in “Shipton Yeti Created Cast,” the post-reconstruction errors were investigated.

In this present essay, I will overview how D. Jeffrey Meldrum, Ph. D., an Associate Professor of Anatomy and Anthropology and Adjunct Associate Professor of the Department of Anthropology, Idaho State University, has revisited and newly reconstructed the Shipton tracks, as well as the more recent Cronin footprints.

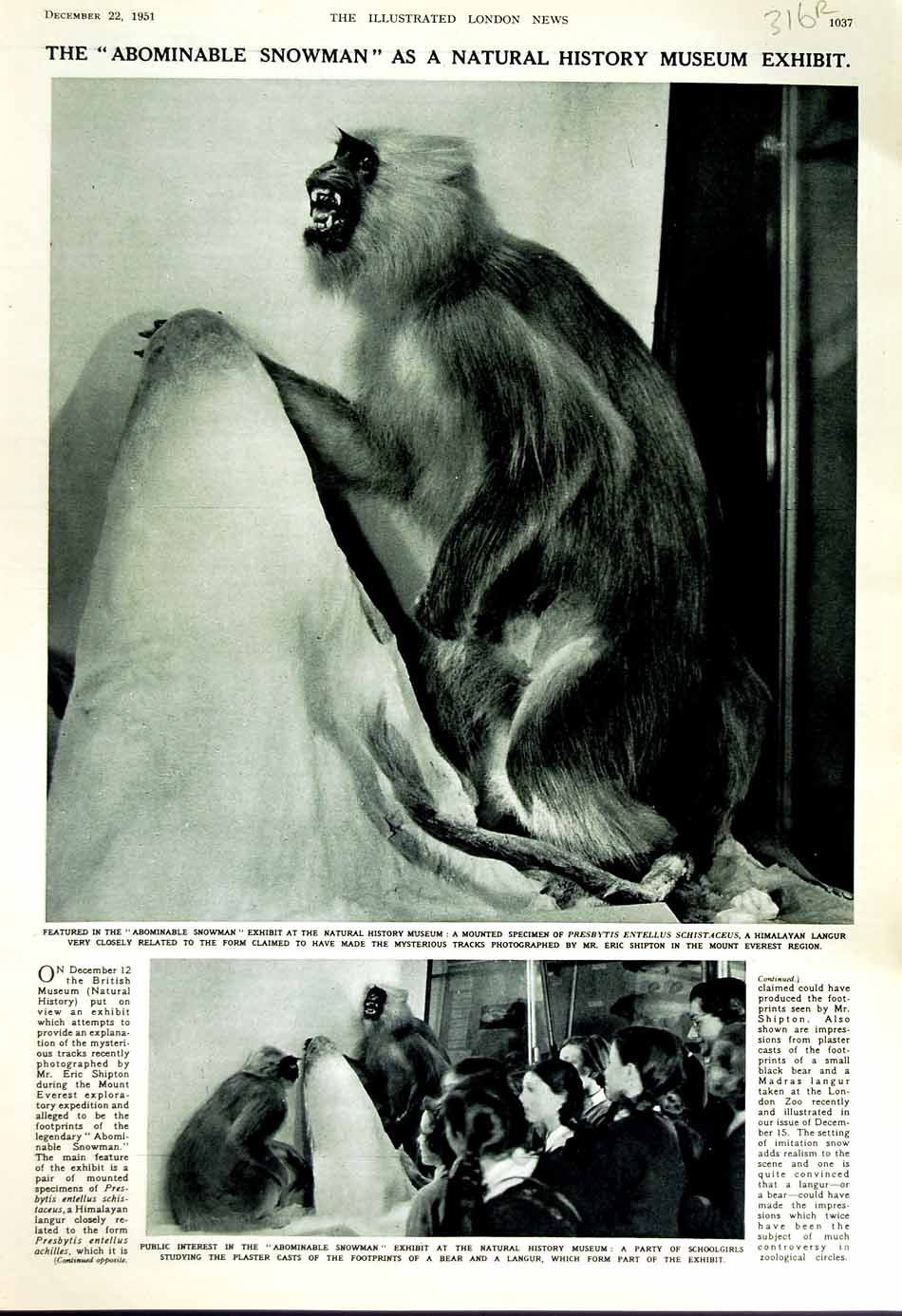

After the Shipton photographs were published in 1951, one of the first attempts to debunk them occurred at the British Museum in December 1951. The major thrust of the exhibit was to present known animals and their footprints to explain the newly found “Yeti tracks.”

One of the favorite candidates of the British Natural History Museum’s effort was what was called, at the time, the Himalayan langur (Presbytis entellus).

But the footprint of the langur does not match the Shipton track.

The bulk of the Shipton 1951 print dwarfed a langur track.

The massive nature of this 1951 footprint especially came forth after the reconstruction of the track from Wladimir Tschernezky’s cast replica (below).

The Shipton track cast was also then reproduced in various forms since 1960.

Grover Krantz shared, in his Bigfoot Sasquatch Evidence (Surry, BC: Hancock House, 1999: 207, Figure 79), the above image with this caption: “Replica of Shipton footprint. A Nepalese craftsman made this image of what the foot should have looked like that made the famous footprint that Shipton photographed in 1951. The original was given to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, where this copy was made through the courtesy of Michael Cohn.”

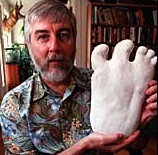

The following cast in Loren Coleman’s personal collection (now at the International Cryptozoology Museum) shows the legacy it owes to the Tschernezky-Cohn designs of the Shipton casting.

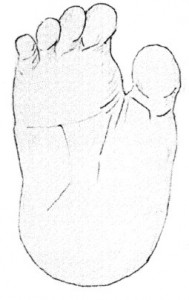

Needless to say, next sketches resulted, such as Ivan T. Sanderson’s drawing identified as “(9) ABSM (Meh-Teh). From photo of cast made from photo of print in snow, by Eric Shipton,” (below). The sketch demonstrates what Tschernezky said he did, via a different kind of cast copy that Sanderson owned, in which the Tschernezky-reconstructed left foot (with hallux on the left) was pressed into snow, cement, or plaster to create a mirror of the footprint (with a hallux image on the right).

Amazingly, even in these discussions of the primary Shipton print, few have figured out that what we are looking at is the imprint of a left foot. Above are the tracks of a human infant, with the left footprint on the left, and the right footprint on the right. But if you fill these depressions, and cast these two tracks in plaster, they flip over and people are confused.

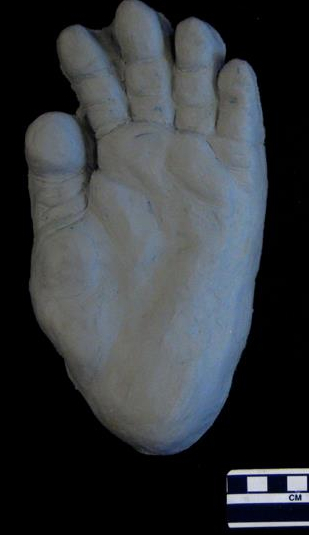

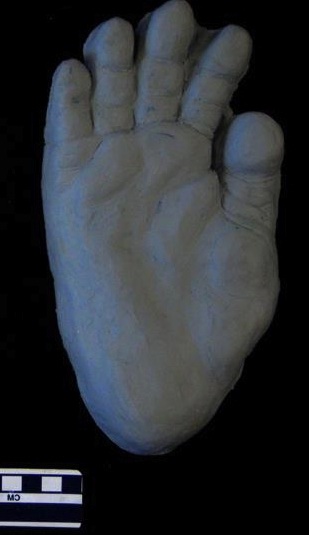

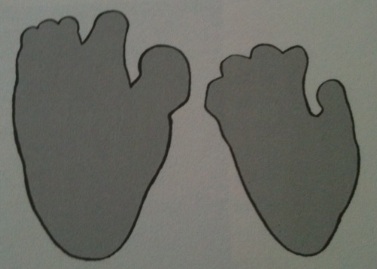

So we arrive at Jeff Meldrum’s interesting new reconstructions of the Shipton cast – on the right – (and the Cronin cast – on the left):

Meldrum’s cast on the left is his newly imagined configuration, from the 1951 Shipton track.

Meldrum sees the Shipton track heel as narrowing and the area around it having been caused by melting. John Napier, Jeff Meldrum, yours truly, Loren Coleman, and others have discussed, in lectures and print for years, that the heel of the Shipton/Ward individual print appears to be distorted by melting. Melting in snow can occur due to the sun, from elevated temperatures, from evaporation, and then be enhanced by wind direction. Therefore, the fact that enlargement would be most visible in the heel is not abnormal.

Meldrum’s caption about his casts, explains: “I did my own reconstruction of the print based on a slightly different interpretation of the relation of the footprint to the pattern of melted ice, giving the foot a more pongid appearance with a tapered heel and divergent great toe (on the right). The enlarged second digit is likely explained as a pathology, i.e. macrodactyly. The other cast is my attempt at reconstructing the foot responsible for the tracks discovered in the Arun Valley by the McNeeley-Cronin expedition.” April 4, 2012.

Meldrum’s cast appears to have been made of a right foot so the human eye can “see” it as the viewer first sees the Shipton imprint in the snow in 1951.

But below I have flipped the cast photograph to actually match the bottom of the foot that would have made the left foot print. As you can see, the appearance is difficult for the human brain to comprehend, upon first viewing it. How can any primate have a foot like this, the brain seems to ask itself? Our eye is so familiar with the “Shipton track,” the Meldrum Shipton reconstruction looks like it is from an alien. But look at it for awhile. You’ll get use to it.

Significantly, in conjunction with the Cronin Yeti tracks, the Meldrum-Shipton footcast starts to make sense.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

“A mind once stretched by a new idea never regains its original dimensions.” ~ Oliver Wendell Holmes

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What are the “Cronin Yeti tracks”?

On December 14, 1972, a four man expedition left their base camp and started on a trek up the Kongmaa La Mountain, Arun Valley, northeast Nepal. The members of the group were two Americans, zoologist Edward W. Cronin, Jr. and physician Dr. Howard Emery and their two Sherpa guides. Cronin wrote of his finds in “The Yeti,” in Atlantic Monthly (November 1975); his book The Arun: A Natural History of the World’s Deepest Valley (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979), and in reprints and remarks in various publications. Cronin, along with his good friends Jeffrey McNeely and Howard N. Emery, wrote of their discoveries in “The Yeti – Not a Snowman,” in Oryx (1973, 12: 65-73).

After easy going, when the Cronin party reached an altitude of about 10,000 feet, the group ran into a storm that made movement and visibility nearly impossible. The guides found a campsite in a valley at about 12,000 feet. Then the weather broke on December 17, and they pitched their tents and fell asleep. Overnight, some thing visited their camp. Emery was the first up the next morning, and immediately saw footprints. He let out a shout. The footprints were nine inches long and almost five inches wide.

Photo of the track of an apparent right foot of a “Yeti” taken by Edward Cronin.

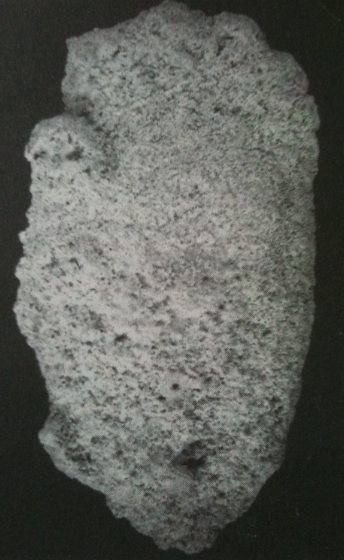

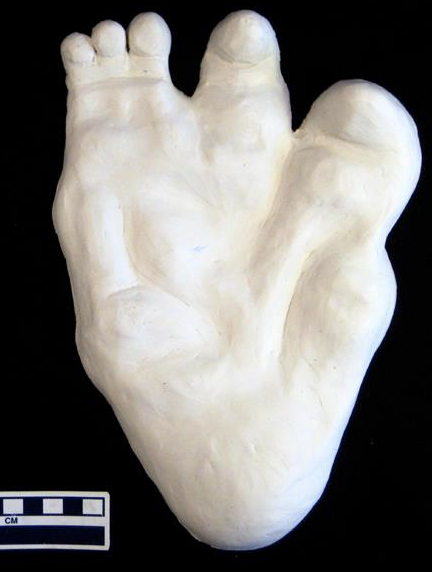

Various prints of a photo of one of the left foot tracks of a “Yeti” taken by Edward Cronin. Photo of left foot cast (as shown, casting does not retain good details from snow).

Emery and Cronin took photographs and later made plaster casts of the tracks. Then they followed the prints until they lost the trail in the bare rocks. Cronin was sure that the footprints had not been made by “any known, normal mammal.” The Sherpas had no doubts that it was a Yeti.

Cronin matched his own tracks left on the night of December 17 with those he made the next morning. Cronin considered all the prints near the camp had remained unaltered by the sun, wind or any of the elements.

The tracks appeared to be barefoot imprints left by a biped creature at night between their tents. The tracks were of 9 inches (23 cm) long and 4.75 inches (12 cm) wide.

The prints displayed precise details. It is visible on the photo that the foot of the hominoid has short and thick big toe put aside to the sole. The other four quite short toes are located widely at front part of foot. The back part of the foot is a wide rounded heel.

Members of the expedition had followed the tracks and found out that the creature approached the camp from the northern slope. From the camp the tracks continued onto the southern slope. Farther the hominoid came back onto the top of the ridge, crossing back and forth several times. Then the creature went down to the south slope where the tracks were ultimately lost in the bare rock and scrub. Cronin noted: “The creature must have been exceptionally strong to ascend this slope in these conditions. No human could have made overnight the length of tracks I could see from the top of the ridge.”

Comparing the images of hominoid tracks by Shipton and by Cronin shows the hallux separate from the middle of the foot on Cronin track is vaguely similar to Shipton’s, but there is no evidence of a larger than normal second digit on the Cronin track.

Zoologist Edward Cronin wrote articles or took extracts from his book, about his finds. These often would contained drawings of Yeti feet or tracks, which showed a left foot from the bottom and a right foot. These appeared in various publications, including Defenders of Wildlife and Atlantic Monthly; Pursuit reprinted the Defenders of Wildlife piece.

In slide presentations, Jeff Meldum, author of Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science, has shown his comparison of the Cronin track cast of a left foot with that of the left foot of a gorilla.

Looking specifically at Jeff Meldrum’s reconstruction of the left foot of the Cronin track (on the left here), it clearly appears similar to the foot of a great ape (pongid).

Flipping Meldrum’s image, to “see” it as a right foot, you can visualize how the bottoms of the left and right foot of a Yeti would appear.

Meldrum’s radical new view of the Shipton track, combined with a more pongid view of the Cronin tracks than ever before, gives forth with new ideas to ponder.

The iconic image of the Shipton track photograph, which has become the “type specimen” for what a Yeti footprint would look like, is based on more melting that most have wished to consider.

The Shipton track may be an enlarged pongid-like footprint, which is also shown in the Cronin imprints.

The outlines (above) of the Shipton footprint and the Cronin print, published by Jeff Meldrum in his book, Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science (p. 41), demonstrates there is more to be found in common, than different, in comparing these probable Nepalese primate’s track finds.

Rarely do artists get the feet right on their Yeti sketches, but you will note that Wladimir Tschernezky certainly tried to technically get them correct. We can only hope, based upon Jeff Meldrum’s thoughtful reconstruction of what Yeti feet may look like, the physical representations will improve in the future.

“There is precious little in civilization to appeal to a Yeti.” ~ Sir Edmund Hillary.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Abominable Snowman, Cryptomundo Exclusive, CryptoZoo News, Evidence, Footprint Evidence, Forensic Science, Men in Cryptozoology, Yeti