June 6, 2009

The recommended new book, Outbreak! The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior is a massive tome, being a large format paperbound book (8″ by 11″), with a total of 765 pages of about 340 entries. The authors are the scholars Hilary Evans, a social historian, and Robert Bartholomew, a sociologist and specialist in collective behavior. The editor-publisher Patrick Huyghe also deserves much credit for being the midwife at Anomalist Books for the birth of this big baby, during the Spring of 2009.

From “Abdera Outbreak of Prose and Poetry” to “Zoot Suit Riots,” the book takes the reader on an incredible tour of the topics at hand. The classics of contagion behavior are here, e.g. the “Band Bus Hysteria,” “Cargo ‘Cults’,” “Copycat Behavior,” “Phantom Slasher,” “Pokemon Illness,” “Salem Witch Hunts,” “Suicide Clusters,” and “Windshield Pitting Scare.”

But it may be the more bizarre of the strange that gets some attention for the authors’ weird little treks into “Extraterrestrial Tsunami Panic,” “Feather Tickling Fad,” “Jumping Frenchmen of Maine” (a little more serious than the “kicking horse game” and “cabin fever”), “Masturbation Delusion” (obviously, an in-depth global survey), “Ugandan Running Sickness,” and “Wacky Wallwalker Fad.”

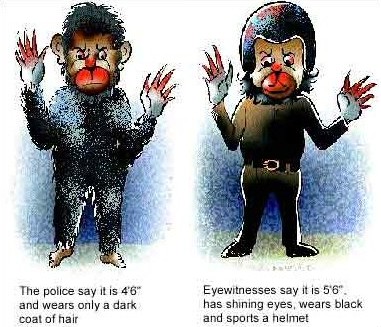

Some personal Fortean favorites of mine, as well as familiar ufological topics, are to be found in this book. They include “Cattle Mutilations,” “Chupacabra Scare” (incorrectly spelled, I must note), “Flying Saucer, Origin of,” “Ghost Rocket Scare,” “Great American Airship Scare,” “Halifax Slasher,” “Mad Gasser of Botetourt,” “Mad Gasser of Mattoon,” “Monkey Man Scare,” and “Springheel Jack Scare.”

The Jack the Ripper case is discussed under the academic entry heading, “Whitechapel Murders Scare,” thus acknowledging the authors’ apparent dislike for the “Ripper” label.

Cryptozoology, per se, also shows up marginally in relationship to a “Water Monster Panic” that occurred in Shanghai, China, in August 1947. An “amphibious monster” scare resulted in the death by drowning of a man who jumped overboard when he heard screams of what he thought was the monster. Two other men were beaten to death by a crowd who “believed they were somehow linked to the monster.”

The entry for the “Windigo Psychosis” covers pages 726 to 728, and is written much differently than how I would approach the subject. The authors begin by clearly defining where they are going here: “Native Canadians of the Algonquin peoples are subject to periodic outbreaks related to a supernatural naked giant to which they give many names but which is chiefly known as the windigo or wendigo, or weetigo.”

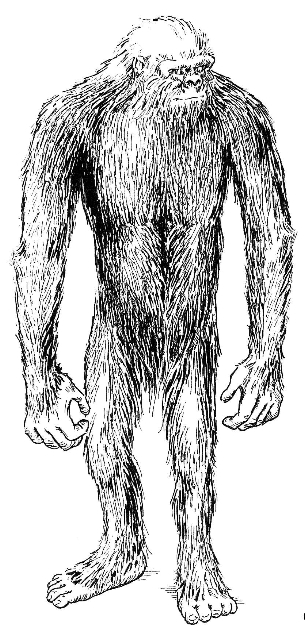

The authors tip their hat by using the word “supernatural,” and give no basis for how the Windigo, a local name for Sasquatch, is viewed by some First Nations people. The real cryptid or unknown hominid is used as the model for the “boogie man” of the psychosis but does not need to be dismissed, out of hand, in their introduction. The windigo psychosis or wittiko psychosis is real, no doubt, but then too, so may be the “monsters of the woods,” the Windigo/Wendigo/Wittiko. The two topics are actually separate but equal, and I see again that the foggy psychosis has caused these writers to pen vague words about the hairy hominid too.

I suppose if you are going to credit an undated article on the “Windigo” psychosis published in the International Journal of Parapsychology for the source of your definition on “Windigo,” versus using more folkloric, anthropological, or cryptozoological references on the creatures, you better be prepared for me to not be happy with that entry.

The Windigo (also known as the Wendigo, Windago, Windiga, Wittiko, Wihtikow, and numerous other variants) is an unknown hairy hominid tied to the sightings, legends and folklore of First Nations people linked by the Algonquin languages. The range is much more broad than given in Outbreak!. The Windigo is a bipedal hairy creature, equal to the Eastern Bigfoot, Stone Giant, or Marked Hominid in some classification systems, which is often said to have aggressive behaviors. But the “Windigo Psychosis” has nothing to do with cryptozoology, except that a name is used for a mental disorder.

I do not hide the fact that I have differences in interpretation with these authors, for I find their black and white skeptical approach to a few of the encyclopedia’s events as being wholly too psychological-based, without any appreciation for the possible underlying factual reality to be found in some of these encounters. I predict that a few thoughtful suicidologists, social scientists or even ufologists reviewing this book would also have a few comments to make about some of their suicide epidemics or ufological entries, as well. It really depends on your point-of-view.

The book is well-organized, but it does take a few moments to understand the reasoning behind why some incidents are entries and why some items are subcategories under others.

The entries bounce back and forth, between the universal and the incredibly specific, such as, for instance, the worldwide “Streaking Fad” to little collections like the “Sick School Staff Syndrome,” and to the minute examples of one event, e.g, the “Ohio Chorus Fainting Fits,” which happened on one day, November 23, 1959.

The index is detailed in small print in 10 pages, and it helps a great deal, if, for example, you are looking for the “penis theft attacks” of 2001, which took place in Nigeria and Benin. Those aren’t mentioned in the section on “Genital Shrinking Scares,” but instead discussed under “Genital Vanishing Scares.” Certainly, an important difference.

Such reservations, however, do not distract me from being grateful these two scholars have written such a fine collection of cases, so we may all have this data at our fingertips now.

The book is a masterpiece, that’s for sure.

It will become a major reference work for those involved in researching these kinds of events or for those with a casual interest who wish to dive deeper into the literature and stories on such things.

Besides merely congratulating Anomalist Books for taking on the monumental task of publishing this important book, also I congratulate them for keeping the price reasonable, at $39.95 US. I already notice used copies are going for $55.21 on the American site, Amazon.com, so I say, if you are the least bit intrigued, buy it new, now.

Outbreak! The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior

Thank You.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Books, Conspiracies, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Eyewitness Accounts, Pop Culture, Reviews, Windigo