The 20th anniversary discovery of one of the largest recent mammals to be found is celebrated during May 2012. But the animal, so newly revealed, may be extinct before we see its 40th anniversary.

May 21, 2012

The 20th anniversary discovery of one of the largest recent mammals to be found is celebrated during May 2012. But the animal, so newly revealed, may be extinct before we see its 40th anniversary.

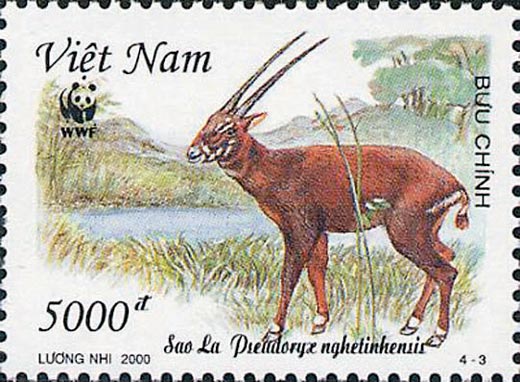

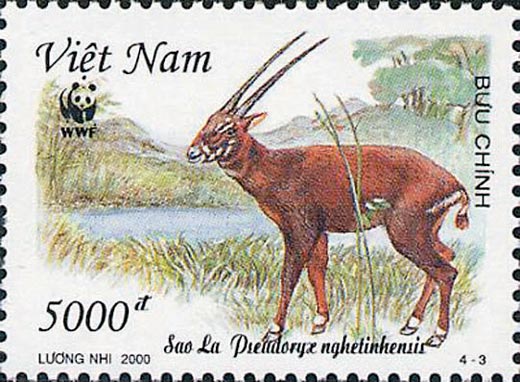

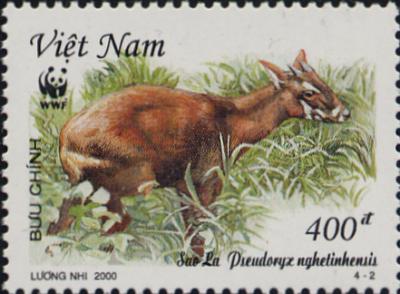

The saola, Vu Quang ox or Asian unicorn, also, infrequently, Vu Quang bovid (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), is one of the world’s rarest mammals. It is a forest-dwelling bovine found only in the Annamite Range of Vietnam and Laos.

Female saola, Lak Xao, Bolikhamxay Province, Laos, 1996. Photo: WWF.

The name saola has been translated as spindle[-horned] although the precise meaning is actually “spinning-wheel post horn.” The name comes from a Tai language of Vietnam but the meaning is the same in the Lao language. The specific Latin scientific name nghetinhensis refers to the two Vietnamese provinces of Nghe An and Ha Tinh while Pseudoryx acknowledges the animal’s similarities with the Arabian or African oryx. Hmong people in Lao refer to this beast as saht-supahp, a term derived from Lao meaning “the polite animal,” because it moves quietly through the forest. Other names used by minority groups in the Saola’s range are lagiang (Van Kieu), a ngao (Ta Oi) and xoong xor (Katu). In the press, Saola have been referred to as Asian unicorns. The appellation is apparently due to the saola’s rarity and apparently gentle nature and perhaps because both the saola and the oryx have been linked with the unicorn (when viewed from the side, only one horn is visible to some observers). There is no known link with the mythical beast; nor with the “Chinese unicorn,” the qilin.

Saola, 2008.

The saola stands about 34 inches at the shoulder and weighs approximately 41 pounds. The coat is a dark brown with a black stripe along the back. Its legs are darkish and there are white patches on the feet, and white stripes vertically across the cheeks, on the eyebrows and splotches on the nose and chin. All saolas have slightly backward-curved horns, which grow to half a meter in length.

The species was confirmed and verified following a discovery of remains in May 1992 in Vu Quang Nature Reserve by a joint survey of the Ministry of Forestry and the World Wide Fund for Nature. The team found three skulls with unusual long straight horns kept in hunters’ houses. In their article, the team proposed “a three month survey to observe the living animal” but, 20 years later, there is still no reported sighting of a saola in the wild by a scientist.

In late August 2010, a saola (shown above) was captured by villagers in Laos but died in captivity before government conservationists could arrange for it to be released back in to the wild. The carcass is being studied with the hope that it will advance scientific understanding of the saola.

The saola inhabits the Annamite Range’s moist forests and the Eastern Indochina dry and monsoon forests. They have been spotted in steep river valleys at about 300 to 1800 m above sea level. These regions are distant from human settlements, covered primarily in evergreen or mixed evergreen and deciduous woodlands. The species seems to prefer edge zones of the forests.

Saola stay in mountain forests during the wet seasons, when water in streams and rivers is abundant, and move down to the lowlands in winter. They are shy and never enter cultivated fields or come close to villages. To date, all known captive saola have died, leading to the belief that this species cannot live in captivity.

The saola belongs to the family Bovidae and genetic analysis places it in the tribe Bovini; in other words its closest relatives are cattle, true buffaloes, and bison. However its simple horns and teeth and some other morphological features are typical of less-derived or ‘primitive’ bovids. Saola are antelopes, in the sense that an antelope is any bovid that is not a cow, sheep, buffalo, bison, or goat. It is not known how many individuals exist, as only 11 have been recorded alive.

Local populations report having seen saola traveling in groups of two or three, rarely more.

Saola caught on a camera-trapped in Bolikhamxay Province, central Laos in 1999. Photograph: William Robichaud/WWF International.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Classic Animals of Discovery, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, New Species