September 16, 2006

This old print of the Steller’s Sea Cow may be made full-size by clicking it.

Could an animal that supposedly went extinct in 1768 still be in the waters of the Pacific?

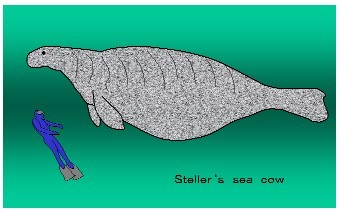

Sirenians are vegetation-eating mammals, which have completely adapted to living in water. In the fossil record, there is evidence of more than a dozen species, but today Sirenia consists of just four species–the West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus), the Amazon Manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the West African Manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), and the Dugong (Dugong dugon)–and two subspecies, the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and the Antillean manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus), both subspecies to the West Indian. These are found in both marine and freshwater, though the Amazon manatee is an exclusively freshwater creature and the dugongs seem to be exclusively marine. Sirenians are commonly referred to as “sea cows,” even though only the supposedly extinct Steller’s Sea Cow (Hydramalis gigas stelleri) should perhaps be called a “cow of the seas.”

The existence of the Steller’s Sea Cow dates back to the Pleistocene, when it ranged the Pacific from Japan to Baja, California. It was first discovered and described for science in 1741 by German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller during explorer Vitus Bering’s expedition to the sea that now bears his name. At that time a population of about two thousand lived in the shallow coastal waters of the north Pacific. These large, rotund animals traveled in herds of males, females, and juveniles, and were said to be gregarious and, for their sake, far too friendly to humans.

Soon after their discovery, fur hunters began to kill the defenseless Steller’s Sea Cow for its tasty meat, and within 27 years, the Steller’s Sea Cow had been systematically slaughtered to extinction. The last Steller’s Sea Cow supposedly died on one of the Bering Islands in 1768.

Where the story of the zoological Steller’s Sea Cow ends, however, the story of the cryptozoological Steller’s Sea Cow begins, as sightings of these animals have continued, off and on, for the last 200 years. Residents of Bering Island claimed that Sea Cows were still being killed and eaten in the area in the late 1770s. A Polish naturalist was certain that Sea Cows had survived on Bering Island as late as 1830 and native reports of the animal were recorded there and in the Aleutian Islands in the mid-19th century.

The above is a selection of passages from The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep. The field guide also details recent encounters with Steller’s Sea Cows.

A Steller’s Sea Cow allegedly washed up on the shores of Cape Chaplin, on the northern end of the Gulf of Anadyr, Siberia, in 1910. In the middle of the century, a harpooner reported regularly seeing 32-foot, finless animals not far from Bering Island in July of every year. The crew of a Russian whaler observed a group of what appear to be Sea Cows in 1962 (see the field guide for a detailed discussion of this sighting), and Russian fisherman walked up to—and touched—a live Sea Cow at Anapkinskaya Bay in the summer of 1976, though this may have been a stray Northern elephant seal. And finally, a Sea Cow skeleton was supposedly found on a Soviet island in 1983.

Now comes a new 2006 report from off Washington State, which might be added to the legacy of the Steller’s Sea Cow.

Writing in an “A manatee, off our coast?” in the Chinook Observer of Long Beach, Washington State, September 13, 2006, Captain Ron Malast writes:

There have some unusual sightings and catches along the Washington Coast this summer, but none more bizarre than the sighting of a manatee. While trolling for tuna on a course parallel to the Big Dipper, at about 40 miles off the coast, I received a radio call from a skipper of another charter boat. The skipper, for whom I have great respect as a fisherman and a straight shooter, wishes to remain anonymous for fear of being put in a straight-jacket and sent to a loony bin.

He said, “Did you see that? It was a manatee. It was bigger than a sea lion and about 12 feet long. At first I did not know what it was, but we cruised closer to it and I looked it straight in the eye. I then knew exactly what it was, it stayed on the surface for about two minutes, unafraid and then slipped off into the deep. When my brother, who was also on the charter boat, and I got home, we immediately got on the computer and pulled up a picture of a manatee and it was the same mammal that we had seen that afternoon. I will remember it to my dying day for what it was – a manatee.”

Zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans was one of the first to recognize the fact that Steller’s Sea Cow may not be extinct. More recently mainstream scientists, as cited in the field guide, such as marine biologists Bret Weinstein and James Patton of the University of California have noted that there are vague reports of Steller’s Sea Cows from along the northwest coast of North America and the northeast coast of Asia, in the Arctic Ocean and Greenland. If such reports are not discounted, then Hydramalis gigas stelleri, or a subspecies, may still be alive today.

Click image for full-size version

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology