December 27, 2009

In a recent Charles Fort Institute blog by Mike Dash, entitled “Baron Von Forstner and the U28 sea serpent of July 1915,” Dash looks at the alleged sighting of a Sea Monster when a U-boat, the U28, blew up an ocean-going steamship in World War I. It is a famous case in Sea Serpent literature, written about in Heuvelmans and discussed by others (including myself and Patrick Huyghe in our field guide) in relationship to marine cryptids.

Here’s Dash’s opening, regarding the case:

This much is beyond dispute: that on the afternoon of 31 July 1915, in the first year of the First World War, the British steamer Iberian was shelled, torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Ireland by the German submarine U28. This much is disputed: that when the Iberian went down, there was a large underwater disturbance – caused, it is supposed, by her boilers imploding. Quantities of wreckage were hurled into the air, and there, amid the debris, six members of the U-boat’s crew beheld “a gigantic sea-animal, writhing and struggling wildly”, which “shot out of the water to a height of 60 to 100 feet.” [Source: Bernard Heuvelmans, In the Wake of the Sea Serpents (London: Rupert Hart Davis, 1968) p.395]

This sea-monster yarn first saw light nearly 20 years later, in the autumn of 1933, at a time when the Loch Ness Monster was much in the news. It was told by the U-boat’s skipper, Georg-Günther Freiherr (Baron) von Forstner (1882-1940), an old U-boat hand who had formerly commanded SMS U1, and who wrote an article about Loch Ness for a German paper that dragged in his own sighting. According to Von Forstner, the creature had also been seen by five other members of the submarine’s crew, all standing in the conning tower. It “had a long, tapering head and a long body with two pairs of legs. Its length may have been some 20 metres [roughly 65 feet]. In shape, it was more like a crocodile than anything else.” [Source: Deutschen Algemeine Zeitung, 19 October 1933]

Dash’s discussion of the case is a good one, and I need not repeat it here. You can find it in his blog. What I would like to look at further here is the suggestion that he writes about from our mutual friend and colleague, Darren Naish, as to the origins of the image of the giant marine crocodile that has developed over the years with this story.

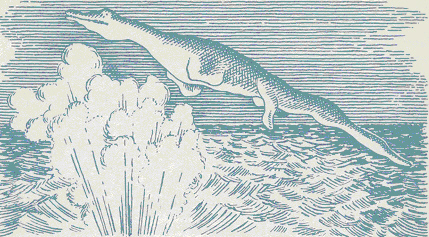

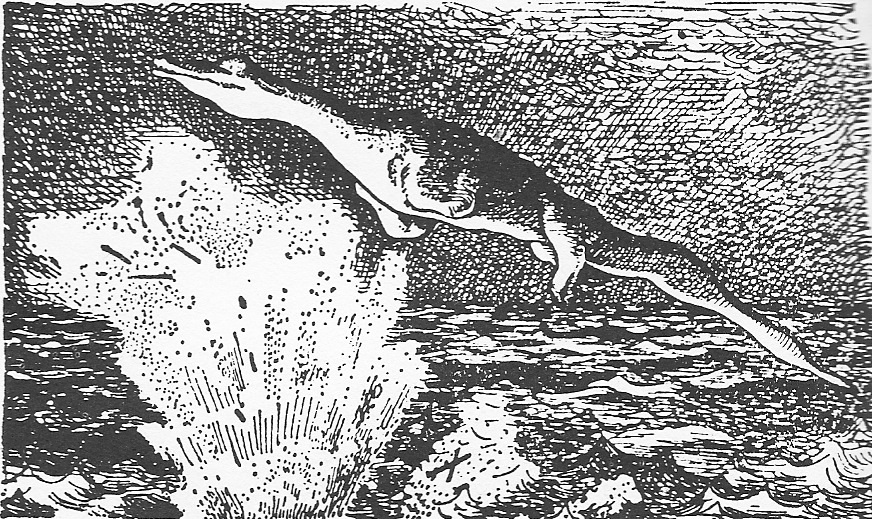

First, allow me to post some of the variations on the drawing that are often reproduced with the retelling of this sighting:

Dash did an excellent job of going over the zoological specifics regarding this encounter, and finished with a flurry by damning the report with an investigation of the historical context.

But I wish to examine the interaction here between the zoology and the art. Allow me to quote this passage from Dash, where he passed along Naish’s thoughts:

There is, moreover, every reason to doubt that the monster, at least as sketched for the Kölnische Illustrierten Zeitung, bore any direct resemblance to the creature Von Forstner asserts he saw. I am indebted to Dr Darren Naish for the penetrating observation that

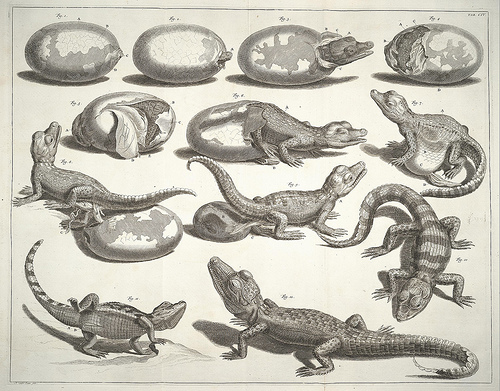

“the more I look at the animal in the picture, the more I think it’s copied from a stuffed specimen of a baby croc/caiman. The head is distinctly juvenile in shape (short rostrum, big eye, bulging cranium). The curled, folded limbs could conceivably have been copied from a contorted stuffed specimen, and the tail is strangely lumpy and mishapen, as is typically the case in badly stuffed crocodilian specimens.”

This theory makes perfect sense, and certainly seems much more plausible, as an explanation for the morphology on show in the famous illustration, than the notion that Von Forstner was able to find an artist, in the Germany of the 1930s, familiar with salt-water crocs – or that the U-boat skipper perfectly recalled an animal he had glimpsed only fleetingly nearly two decades earlier, and was able to describe it with precision for his artist.

Cryptozoological literalists, I have no doubt, will easily rationalise all this by suggesting that the U28 had encountered an as-yet-unknown species of giant marine crocodile, adapted to life in northern latitudes, yet so elusive that, a century after Von Forstner’s alleged observation, neither further sightings nor a specimen have come to light.

Now, heaven forbid, I be thrown into any “literalists” camp, but I want to point out a couple things about the mere conjunction here of taxidermy, croc mounts, art, and illustrations.

While Naish may be correct that it looks like a juvenile taxidermy mount of a crocodilian, I immediately thought I noticed something about the famed drawing that appeared to work against that origin. Most mounts of crocodilians tend to display the jaws wide open. I surveyed several images on the web and stared at the ones I have in the museum, for too many minutes. Darn it if they all didn’t have their mouths wide open. It appears to be a rather too common way of taxidermy presentation of crocodilians to ignore.

David Carkhuff photo.

But, guess what, Naish appears to be correct about the juveniles being drawn and mounted, more often than not, with mouths closed.

Something seemed familiar beyond that, however.

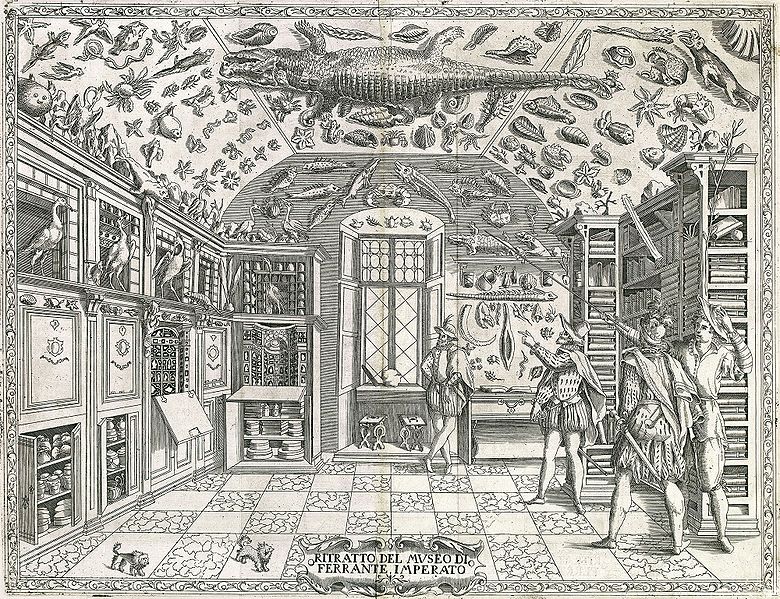

As an art motif, I’d like to suggest an additional possible origin for the very strange look of this “croc in the air” of the Kölnische Illustrierten Zeitung image reproduced and reworked so often: old European cabinets of curiosities.

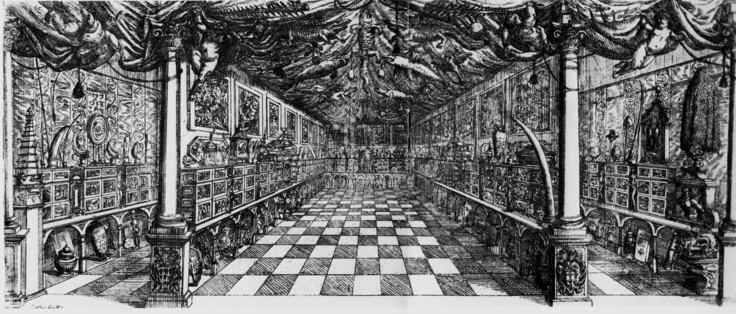

What is found over and over in old paintings, sketches, and drawings of cabinets of curiosities? A crocodilian of some sort hanging in mid-air from the ceilings of these collections.

I propose that the U28 Sea Monster drawing has a strong link to that singular reoccurring motif. As you can see below in such early cabinets of curiosities or wonder, traditionally called Wunderkammer, there you have a crocodile (sometimes an alligator) floating in the air. Look closely, and you can see them in these sketches.

Ferrante Imperato of Naples is the first known representation of a cabinet of curiosities. It was published in 1599.

Some of these have been preserved, as can be found in the Gasser Wunderkammer:

Other modern examples exist.

This is from the Trausnitz Castle in Bavaria, from its refurbished Wunderkammer, 2004.

One taxidermist, living in France, writes that William Shakespeare’s first definitive written use of “alligator” in the English language was in “Romero and Juliet,” when it is noted the apothecary’s “needy shop a tortoise hung, an alligator stuffed and other skins of ill-shaped fishes.”

As this blogger Pomposa also added, “In the good old days stuffed crocodiles were often suspended from the vaults of churches, especially in Italy, to drive away demons.”

Demons and monsters, it would seem, go foot and foot together.

If we look for the precursors, even of the Wunderkammer itself, we only have to examine tourist photographs, like the one below from modern Egypt, where in a Nubian village, this is how dead crocs for sale are displayed.

Flying crocodilians are all about us.

Maybe Mike Dash’s and Darren Naish’s speculations are correct as to the weak reality behind the U28 story. Naish may even be right that in it he sees a juvenile taxidermy mount of a croc. Finally, beyond that, perhaps the deeper origins of the episode is an extension of a long-standing art motif that might help explain the rather strange nature of that croc in the air ~ as a renegade from the mind of a German artist who had been schooled in the ways of the Wunderkammer!

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Crazy Crocs, CryptoZoo News, Eyewitness Accounts, Giant Cryptid Reptiles, Living Dinosaurs, Living Fossils, Replica Cryptia, Sea Serpents