April 6, 2010

The newest issue, No. 14 of The Anomalist is out. Entitled “Electricity of the Mind,” it is filled with material to challenge your brain. Some of it specifically deals with cryptozoological topics.

Following, I’ll post three of the blurbs from TA, of some articles of interest to Cryptomundo. These I shall then follow with my own input. From the several chapters in this nicely bound booklet, the journal has these that you might enjoy reading:

(1) “The Topography of the Damned” by Theo Paijmans.

“Theo Paijmans mines the rich seam of digital newspaper archives to look at anomalies in a new way, by mapping the geographical distribution and dispersion of the account of the anomaly event through time and through various newspapers, tracking the mutations and elaborations that set in as the story spreads.”

I was surprised and delighted to read that this well-researched contribution by Paijmans looks closely at the history, through newspapers and journalistic copycatting, of mostly winged weirdies and flying human stories that pre-date Mothman accounts. Paijmans dug through the surveyed archives he notes, quite expertly, to take us far beyond the citations in Charles Fort and other authors (including me) to discover the deeper truths behind some of these accounts. This is a masterpiece article by Paijmans.

(2) “The Continuing Strange Tale of the Thylacine: A Growth Function for a Small Population” by Chris Payne.

“Are there still Thylacines out there? Chris Payne takes a new mathematical approach to trying to determine whether this is at all likely, and if it is, when we might expect to get a definitive answer to the question.”

Using math models in cryptozoology is nothing new, as Charles Paxton has demonstrated in his exercises in predicting marine and freshwater species discoveries. Here Payne does something similar for Thylacines, and considers, quite logically, the possibilities and final end game on the species probable existence and extinction.

That is the good news. The rest of the article, which is painful to read, every pun intended, is the bad news.

Unfortunately, the editor of this piece, Ian Simmons, failed to catch some gross mistakes that Payne let slip into his article, such as misspelling the name “Bernard Heuvelmans” in the text and references as “Heuvelmanns,” and noting the okapi was first discovered in 1930, instead of the correct year, 1901.

Because this was a previous journal article, was it merely greenlighted to go as is? If so, that’s too bad.

More difficult internal errors that fill this paper are used as introductory remarks, which may have been there to get this published in the math journal in which it originally appeared. The author Payne takes a less-than-cryptozoology-friendly approach in the beginning, mixing up Yetis and Sasquatch, and, seemingly with debunking tongue-in-cheek, acting as if cryptozoologists are searching the “high altitudes” for these “gigantic apelike creatures.” Of course, cryptozoologists are aware that montane valleys, not snowfields, are the places to look.

Furthermore, Payne says silly things like, “Fortunes must have been spent searching for the Loch Ness Monster, which cryptozoologists still look for in spite of all the evidence that ‘sightings’ of it have always been attributed to natural causes such as floating matter or the self-delusion of the observers. No amount of scientific persuasion seems to be enough to convince Nessie fans that a pod of pleisiosauri (sic) could not possibly survive in an enclosed area from the age of dinosaurs,” (The Anomalist #14: 125).

Needless to say, even a mathematician should be able to use a spellchecker, and conduct enough research to learn the fact that Loch Ness does have close land and river access to the ocean. Furthermore, the Scottish lake was only created several thousand years ago, not millions. Most American cryptozoologists, by the way, are aware of several mammalian explanations for the cryptids in Loch Ness that have nothing to do with marine reptiles.

But most of all, people who work with math must know the dangers of using a word like “always”! Anyone that says that every report of the Loch Ness Monsters are “always” based on the two explanations noted by Payne must not be very well-read in the cryptozoological literature.

So, according to Payne, “Cryptozoologists are romantics.” Perhaps so, but, at least, we usually get our dates of discovery correct, and don’t confuse absolutes, possibilities and probabilities, as this mathematician appears to have done in his opening comments.

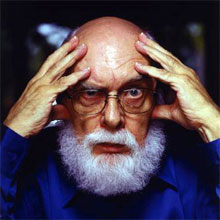

(3) “The Real James Randi” by Tim Cridland.

“Tim Cridland is best known for his startling human blockhead act for the Jim Rose Sideshow Circus, but here he takes a long, hard, critical look at the career of leading skeptic James Randi and some of the inconsistencies it seems to contain.”

What is most interesting about this overview of Randi’s life is to now read it in light of the double life that James Randi has indeed lived. As some readers here may know, James Randi just came out of the closet to reveal he is gay. Considering how harsh he has been on others, one wonders how this all plays out in light of his sometimes extremely personal attacks on those he has critiqued, whom it would seem, he often called to task for not being forthright enough.

Swift, named for Jonathan Swift, is the James Randi Education Foundation’s daily blog, featuring content from James Randi and others. He used that forum on March 21, after seeing the movie Milk the week before, to declare himself to be “gay.”

+++

For more information about obtaining The Anomalist #14, click here.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Books, Breaking News, Classic Animals of Discovery, Cryptomundo Exclusive, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Eyewitness Accounts, Forteana, New Species, Skeptical Discussions, Thylacine, Winged Weirdies