March 16, 2009

Okay, I know you are familiar with the drawings like the following from the West Coast of North America, of Cadborosaurus or Caddy, the Sea Serpents off the PNW.

The high art representation of Caddy is also now well-known. It is shown below, on the cover of the most pivotal book produced on the cryptozoological search for these cryptids.

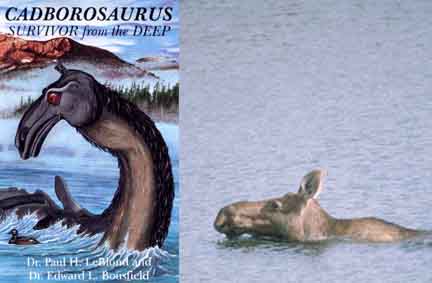

Nevertheless, we do have to be open to examining this intriguingly insightful drawing-photo comparison, now don’t we?

(Credit: Loch Ness Investigation)

Moose (North America) or elk (Eurasia), Alces alces, however, are lake and river swimmers, and not often seen out to sea.

But seriously, the most silly of the photographs presented for the mirror image aquatic monsters, Cadborosaurus and Ogopogo, generally look similar to the following.

Look, look, quick, hey, the one below is not a fake or fuzzy blobmonster photo!

It turns out it is an otter. Observers first spotted this sea otter cavorting in the waters of Depoe Bay twice in February 2009, in front of the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department’s Whale Watching Center. The last of Oregon’s native sea otters disappeared in 1906, and marine scientists are trying to determine the residency of this otter. (Courtesy, Morris Grover)

Of course, without the photograph, no one would have believed these sighting reports, if recent history is any guide.

“There have been sightings through the years, so it’s not unprecedented,” said Jim Rice, coordinator of the Oregon Marine Mammal Stranding Network at Oregon State University’s Hatfield Marine Science Center. “But most of the so-called sea otter sightings have been river otters. It’s a good likelihood this is a wandering animal from Washington or California.”

Several folks, among them at least three staff members of the Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area, spotted what they thought was a sea otter just west of the Yaquina Heads Lighthouse on January 13, 2009, and reported the sighting to Rice. They watched it for about 45 minutes through binoculars and spotting scope before it swam northward around the headland and out of sight.

“They described a good-sized otter-like animal swimming on its back, initially in close proximity to a large rafting group of common murres,” Rice noted in an e-mail report about the encounter. Two of those observers were rangers with the Bureau of Land Management “who seem to have a good understanding of the differences between river and sea otters.”

In May 2008, Rice spoke to someone convinced he had seen a pair of sea otters through a spotting scope just west of Otter Rock off Beverly Beach.

No confirmation was possible in either sighting, which makes the February 18, 2009, certification significant, according to media reports.

Now, a little farther north, there is a new report, the first since 1913, of a sea otter sighting in Washington State, near the appropriately name Cape Disappointment.

Imagine their excitement when Jen Zamon and Beth Phillips, seabird researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Point Adams Research Station, spotted a sea otter from North Head.

Sea otter sightings around the mouth of the Columbia River are extremely rare. Sea otter populations are still recovering from the days of the fur trade, when the West Coast population was nearly wiped out for its luxurious undercoat of fur.

The first modern Columbia sighting was on Thursday, March 12. The women from NOAA were performing their routine seabird and marine mammal survey near the North Head Lighthouse. Floating on its back, several kilometers offshore was a sea otter. They trained the “big eyes,” binoculars with grapefruit-sized optics, on the animal to confirm they were seeing a sea otter. They were treated with the quintessential pose – a sea otter floating on its back, rubbing its face with its forepaws.

Later in the week, another sea otter was spotted at Cape Disappointment State Park by Jon Schmidt and Aaron Webster from the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center. They got to see the sea otter floating on its back with something resting on its chest. “It appeared to be a crab,” said Webster, who cupped his hands to make an oval shape about 8 inches across.

In February, a sea otter was observed in Depot Bay on the Oregon Coast, where they have been extinct since 1906.

In June 1913, the Chinook Observer enthusiastically reported the very tail end of an era when it announced: “The first otter seen on the North Beach [as the Long Beach Peninsula was then known] for five years was sighted off Willapa Harbor Sunday by … a crab fisherman. Seven of the otters appeared in one family and were quite tame. Three of them were killed, and one was a ‘silver-tip,’ eight feet in length, with a pelt valued at $1,200. The value of the pelts range from $100 to $1,500. Formerly otters were numerous along the beach, but disappeared completely a few years ago. Their return means the reopening of the business of otter hunting, which made fortunes for many a fisherman years ago.”

Most purported “sea otter” sightings in modern times are really just river otters taking dips in the ocean. Both species are members of the weasel, or mustelid, family, a group that includes everything from minks to wolverines. But sea otters and river otters are about as different as pit bulls and Chihuahuas. Several characteristics can help you identify which type of otter you are seeing: “An adult sea otter can be about four feet long (excluding the tail) and weigh in at about 100 pounds. (River otters, by comparison, grow to about three feet long (excluding the tail) and max out at about 30 pounds.) Sea otters are stout animals with a thick multi-layered coat of fur. The fur on their bodies is dark brown while the fur on their heads is usually a lighter tan color. All four feet on a sea otter are webbed, with the back feet looking more like the flippers of a seal. If the otter you see is dark-bodied with a light head, it might be a sea otter.”

* * *

Because sea otters are so rare, confirmed sightings are important to report. If you see a sea otter, gather as much detail about the sighting as possible – its color, what it was doing, and where it was – then call the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at 360-753-9545 to report your sighting. by Julie Tennis, Washington State Parks, Source

Okay, so there are otters there and they are back. People who said they had been seeing them were not insane.

So maybe, just maybe, could there still be room for a pod of Caddys swimming around in the marine environment off the coast of Washington State and British Columbia?

Jeff H. Johnson’s sculptured model of Cadborosaurus.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Blogs are free. Saving the International Cryptozoology Museum from selling off its contents and/or going into foreclosure in the next few months is no joke.

The next six months are critical. Your help is needed. The IRS troubles put the museum in an incredible hole. Please remember to donate to the museum, in any amount, and today you may use PayPal to lcoleman@maine.rr.com (not the Cryptomundo button above), direct a check, money order, or, if outside the USA, an international postal money order made out “International Cryptozoology Museum” to

International Cryptozoology Museum

c/o Loren Coleman

PO Box 360

Portland, ME 04112

An easy-to-use donation button (FOLLOWING) is available merely by clicking the DONATE button below, which takes you to a donation site without you having to be a member of PayPal. Thank you, everyone!

Where are all the cryptozoology donor angels? What will your post-Heuvelmans’ legacy be? A donation of $10 is just as important as one for $100. Want a special display dedicated to your favorite cryptid, in your honor for a $2000 donation? $10,000? 🙂

As mentioned before, the ICM is not a 501(c)3. But the credit to your soul is worth a good deal more. 🙂 Thank You.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Extinct, Eyewitness Accounts, Lake Monsters, Merbeings, New Species, Ogopogo, Sea Serpents