February 7, 2007

Did a young girl from a pioneering Fiordland family have the last human encounter with a moa?

It has gone down in history as one of the most puzzling rare-bird sightings and it happened in the remote south-west corner of New Zealand.

What was the big blue bird that pioneer Alice McKenzie saw at Martins Bay, 30km north of Milford Sound, in 1880? Experts are still debating nearly 130 years later.

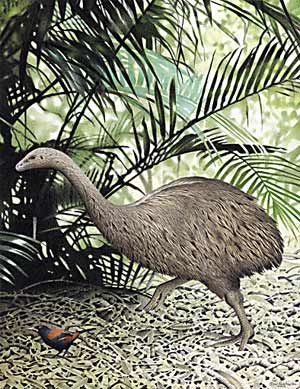

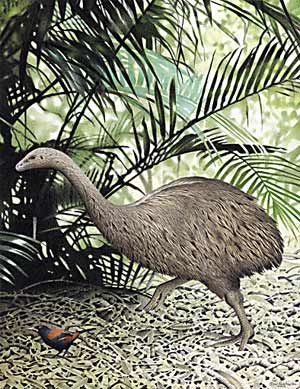

Did a species of moa, such as the little bush moa, survive human predation and live on in the Fiordland wilderness 400 years after they were thought to be extinct?

Or was McKenzie, whose meticulous diary jottings of everyday life have been hailed as a valuable historic record, genuinely mistaken over her blue “moa”?

Forty-four years after her death, McKenzie’s memory is being defended by her Christchurch granddaughter, Alice Margaret Leaker. She has compiled a new edition of a book her grandmother wrote, first published in 1947. The new edition of Pioneers of Martins Bay, published by Arrowtown’s Lakes District Museum, delves further into “moagate” and responds to the critics who say McKenzie was wrong.

It is a huge claim for anyone sober to say “Nana saw a moa” and Leaker chooses her words far more judiciously than that.

“I believe that she saw what she said she saw. What she has described sounds very like what we now know the bush moa to be,” says Leaker, 61.

Her maternal grandmother was born in Hokitika in 1873 to Daniel McKenzie, a Scottish journalist, and his Irish wife, Margaret.

Alice was about five when the family settled on a farm near the beach at Martins Bay. She never went to school, but left behind journals recording daily realities facing pioneers in the 19th century, poems and the legacy of her book.

It was in 1880, when Alice was seven, that she says she saw a large blue bird under flax where the bushline met the beach. This was not a flash of a bird retreating into the scrub. It was a full-on encounter, with Alice describing touching the bird’s curved rump feathers and stretching out one of its dark-green, scaly legs.

It was only when Alice tried to tether the bird with flax that it let out a “harsh, grunting cry” and chased her for a short distance.

McKenzie described the bird as being pukeko blue, with legs as thick as her wrist and no noticeable tail. When it stood up, it seemed as tall as she was.

She caught another glimpse of the bird in 1889, then nothing.

In Pioneers of Martins Bay, McKenzie said she believed for a long time that the bird must have been a takahe. But when the takahe, thought extinct, was rediscovered in 1948, McKenzie said the description was very different from the bird she had seen. She went to the Otago Museum in Dunedin to see a mounted takahe and found it much smaller – with red legs and beak.

McKenzie died in 1963 in her 90th year, after a series of strokes.

Leaker’s life overlapped with that of her elderly grandmother when McKenzie lived with the extended family in Dunedin.

“I would say she was a very truthful, good person. A Godfearing person. I could never imagine that she would have been the kind of person to make something up for attention,” says Leaker. Although she never got the chance to talk to her grandmother about the sighting, Leaker remembers being fascinated by adults discussing it.

“It’s not until you grow older that you come to realise how important it is. And wouldn’t you love to have someone back for a couple of weeks so you could talk to them?”

However, critics such as respected author John Hall-Jones are far from convinced. In his 1987 book, Martins Bay, he felt a strong need to “correct” McKenzie’s claim to have seen a moa.

“Indeed, it is paramount to do so, for if it was true then it would be the only documented case of a European having seen and actually touched a living moa. And it would be the first report of a moa, dead or alive, with navy-blue feathers”.

Hall-Jones further pointed out that the moa story only came to light in the second edition of McKenzie’s book, published in 1952, when she was 75.

In 1946, McKenzie had written to an Otago University professor claiming to have seen a takahe, before their rediscovery.

Hall-Jones ventured that McKenzie may have seen a blue white-faced heron, which, with its long legs and large feet, would have looked huge to a child.

“Above all, it must be remembered that we are depending on the observations of a child aged seven, first reported at the age of 69 and altered significantly at the age of 75,” wrote Hall-Jones.

Today, Hall-Jones is holding firmly to his view. “She’s got her view and I’ve got mine. The archaeologists and ornithologists agree with me over it, too. I don’t really want to get involved in a showdown.”

The need to respond to her grandmother’s critics, and preserve history for her own three sons, prompted Leaker to produce the new book.

“Her (McKenzie’s) many accounts of these incidents have been very descriptive and consistent,” says Leaker.

“It is interesting to read her diaries and to realise how familiar the family must have been with the bird life that surrounded them at the time, even if they did not know them all by name.”

Leaker is aware that prevailing scientific opinion opposes her grandmother’s sighting because of the timing. “They really don’t believe that she could have seen one, but there are just so many accounts of sightings in the 19th century in New Zealand,” Leaker says.

She says a pending publication on moa sightings will cover reports such as McKenzie’s in a thorough and balanced way.

Academics contacted by The Press had little hope that McKenzie’s bird was a moa, but neither did they entirely rule it out. “It is not impossible,” says Canterbury Museum’s curator of vertebrate zoology, Dr Paul Scofield.

However, moa experts agreed it is “highly unlikely”. “The bottom line is that the conventional wisdom is (that) most moa became extinct within 100 years of the first human arrival in New Zealand in the 12th century,” Scofield says.

Evidence suggested a few small upland moa may have been living in the high country until about 1500, he says.

“Current evidence suggests that all moa were extinct by 1500.”

Scofield says the species McKenzie could have seen – the upland moa – was least like the description she reported.

“The upland moa had some very weird characteristics – for example, hairy legs – and it was only as big as a sheep, really,” he says.

The colouring of McKenzie’s bird pointed more strongly to the takahe, but there were other possibilities, says Scofield.

Unusually large, great spotted kiwis the size of turkeys were known to exist in the area at the time. Exotic birds like ostriches and emus were released in parts of New Zealand during the late 1800s because experts believed that native birds were doomed.

“That is also a possibility,” Scofield says.

Te Papa’s fossil curator, Alan Tennyson, says a pukeko-blue moa does not tally with any recovered moa feathers.

“The bright-blue colour would suggest something like a takahe, which probably were there at the time, but her description doesn’t really fit with a takahe, either,” he says.

“That’s the problem with these sorts of sightings. It would never be accepted as a definite moa. It obviously is an interesting sighting and it doesn’t sound like it’s fabricated. It sounds like she genuinely saw something there.”

Being so young at the time, Tennyson says McKenzie’s imagination may have influenced the sighting, especially if it was recorded years later.

With the passage of time it is almost impossible to solve the riddle of the blue moa, but as folk from Loch Ness know, that is what keeps a good legend alive.

* Pioneers of Martins Bay will be launched next Saturday at the Lakes District Museum, Arrowtown. The museum is selling the book direct for $29.99.Yvonne Martin

Source: Stuff Magazine, New Zealand, February 6, 2007. Thanks to The Anomalist.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Books, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Eyewitness Accounts, Museums