October 15, 2010

Henry Gee is a senior editor of Nature. He blogs at The End Of The Pier Show. He will be speaking at the Grant Museum, University College London, UK, on October 26, 2010, at 6:30 pm, in the UCL Darwin Lecture Theatre. The admission is free.

In line with Gee’s forthcoming talk, some of his thoughts were published recently in The Guardian under the headline, “Indiana Jones and the Sasquatch of Doom.”

The piece is thoughtful and very reflective of the insights you often see expressed here. Following is an excerpt of that article (retained in normal font to emphasis the italics for the Latin names in his original piece):

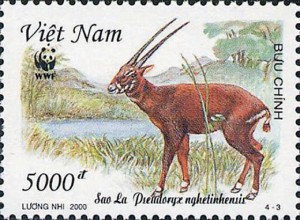

As recently as 1993, a scientific paper landed on my desk at Nature describing a species of antelope hitherto unknown to science. And not some cute little creature that could slip between your knees and hide coyly behind a leaf, but a beast big enough to bump into, and do you serious injury if it stepped on your foot. How could people in this overcrowded world have missed it?

The location was a start. The saola, for such is its name (its more formal handle is Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), comes from the remote and deeply inaccessible Annamite Mountains on the border between Laos and Vietnam, a kind of Lost World known for hosting other rare species. Even if you can hack your way in, the saola is pathologically shy, and goes out of its way to go out of its way.

The scientific description was not based on a live animal, or even a dead one, but hunting trophies – horns, skulls and skins of several animals collected from the houses of local hunters. The live animal had not been seen. To my perhaps jaded editorial eye, the report seemed to have come straight out of King Solomon’s Mines. How romantic!

The saola is, in fact, so shy and secretive that it wasn’t until 1998 that it was photographed alive in the wild – and then only fleetingly. In 1999 it disappeared from view altogether. It was only in September 2010 that a live saola was captured. It obligingly stayed alive long enough to pose for its portrait whereupon it expired, presumably unaccustomed it its unwanted celebrity. The number of saola in existence is unknown, but it is likely to be small, and getting smaller all the time.

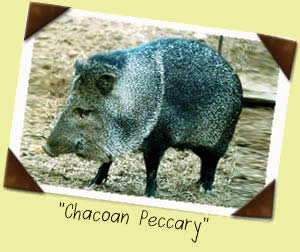

The saola joins a select band of large mammals discovered relatively recently, all of which are (not surprisingly) rare to the point of vanishment. A wild pig, the Chacoan peccary, Catagonus wagneri, was known only from fossils until it turned up on the wild borders of Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina in 1975, and is believed to be hanging on by its trotters.

A wild ox called the kouprey, Bos sauveli, a cousin to the saola, was described in Cambodia in 1937. There were around 1,000 of them in 1940; down to around 100 in 1969; and it hasn’t been seen at all since 1983. This strongly suggests extinction, as creatures as big and beefy as the kouprey would be hard to miss.

Other creatures hardly touch the zoology texts before disappearing entirely: the red gazelle, Eudorcas rufina, is only known from skins discovered in Algerian souks in the nineteenth century. It has never been seen alive.

That such large creatures roamed the Earth until present times before dying out is a reminder of humanity’s remorseless conquest – hackneyed, to be sure, only because of its frequency of repetition. But there’s a wider point to be made here, about how little we know even about large mammals (let along squashy creatures from the abyss, or microbes), and the degree to which the documentation of recently extinct creatures grades from certain knowledge into myth. The Chacoan peccary was known from fossils until live ones were found. The saola was described from trophies before live examples were seen. The red gazelle is only known from such trophies. And where antelopes, oxen and pigs lead, humans will follow.

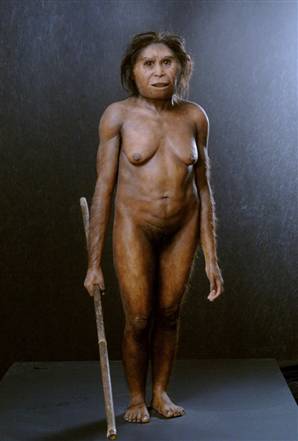

If stone tools are any guide, human beings – of one sort or another – have been living on the relatively far-flung island of Flores in Indonesia for a million years at least. By “one sort or another” I mean exactly that – as far as we know, modern humans didn’t arrive on Flores until a little before 10,000 years ago. The previous residents were (presumably) related to the extinct form Homo erectus.

The announcement in 2004 of an entirely unknown species of extinct human that lived on Flores – Homo floresiensis, or “The Hobbit” – caused a sensation. The small size and unique morphology of this creature is still a field of battle between those who contend that it is a real species, against those who think it is a diseased form of modern human. But what is really remarkable is the age. Initial findings showed that H. floresiensis lived on Flores from before 38,000 years ago to as recently as 18,000 years ago. Further work extended the range from as long ago as 95,000 years to as recently as 12,000 years ago.

Given the great age of the Earth, 12,000 years is very much less than an eyeblink. That an animal became extinct 12,000 years ago, or yesterday, hardly matters, for in the great scheme of things, this difference is insignificant. If the Chacoan peccary came to life from fossils, and if the saola emerged alive – if only just – from the Annamites, it is entirely legitimate to ask whether H. floresiensis, or something like it, still exists, or, perhaps, became extinct in historical times: a human version of the red gazelle, perhaps.

And if one admits H. floresiensis to the canon, what of other celebrated mythical beasts – if not necessarily Nessie, then the orang pendek of Malaysia? The yeti? The sasquatch? Bigfoot? Are all such creatures the products of delusion, conspiracy theories and hoax? Perhaps – but not necessarily. The little we know of those large mammals on the fringes of knowledge suggests that they live in remote places, are very shy, are extremely rare, and that to find them before they become extinct requires a degree of luck. So far, no hard evidence for yetis (say) has emerged. But in a world that hosts H. floresiensis and the saola, the kouprey and the red gazelle, one should keep an open mind.

(Please consult the source for more.)

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Classic Animals of Discovery, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Cryptozoology Conferences, Homo floresiensis, Living Fossils, Men in Cryptozoology