December 21, 2007

The rare Nigerian giraffe, known currently as Giraffa camelopardalis peralta. Photo: Michel Carossio

Last night, for whatever reason, after watching a bit of film showing the megafauna of Africa, I found myself trying to sort out the many subspecies of one animal – the giraffe. No, I wasn’t even looking at the zebras. I ignored the gnus, antelopes, rhinos, and elephants. But, I had to concentrate on the giraffes.

I pulled out two field guides, Jean Dorst’s and Pierre Dandelot’s A Field Guide to the Larger Mammals of Africa (1969) and Jonathan Kingdon’s The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (1997). I knew as a young boy I had all the subspecies memorized. But that was a long time ago, and I never made it to Africa, so my self-taught lessons had faded. After studying into the wee hours, it seemed fairly clear that more subspecies had been added and the situation had become more complex.

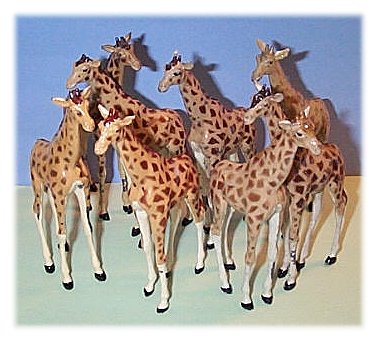

Not being near a zoo and not having any giraffes out in my backyard, I figured I would see if I could identify, specifically, the giraffes in my replica cryptia and related animal collection. I happen to have a few, five adults and three young. It became clear that one “toy” was not based on any reality other than an animal artist’s imagination, but the others, near museum quality, seemed to represent four different subspecies.

I was struck by how diverse the giraffe subspecies may have become, a long way down the road from okapis.

Directly above, a group of antique Britains giraffe replicas. Can you identify what kind of giraffe is represented?

Thus, it was with some surprise that the first thing I found in the way of new animal news this morning was an announcement about giraffes. The supposed one species of giraffe, which have generally been divided into many subspecies, might actually be 6 to 11 separate species.

In this new view of giraffes, in the midst of this great “new species” discovery news, of course, is bad news too.

One type found in West and Central Africa is on the verge of extinction, the Nigerian giraffe (currently Giraffa camelopardalis peralta), shown in the photograph at top. The Nigerian giraffe is down to only 160 known individuals.

In the December 21, 2007 issue of BMC Biology, scientists have detailed this new genetic study. The research was conducted by an interdisciplinary team from the University of California, Los Angeles, the Henry Doorly Zoo, Omaha, Nebraska, and the Mpala Research Center, Kenya.

“Some of these giraffe populations number only a few hundred individuals and need immediate protection,” said study leader David Brown, a geneticist at the University of California, Los Angeles and an associate with the Wildlife Conservation Society. “Lumping all giraffes into one species obscures the reality that some kinds of giraffe are on the very brink.”

“Giraffes are often overlooked in conservation initiatives, but they are as symbolic of African wilderness as any other species,” said Dr. James Deutsch, Director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Africa Program. “Studies such as this one will help us inform conservation plans to save the most threatened giraffe populations.”

Besides the extremely rare Nigerian giraffe, the most threatened potential species is the reticulated giraffe (currently Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata), rather familiar to zoogoers. The reticulated giraffe is found in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, reduced from a population estimated at some 27,000 individuals until the 1990s. Poaching and armed conflicts have decreased this group now to 3,000 individuals.

The Rothschild giraffe (currently Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi), which was formerly found in western Kenya and Uganda, can only be located in a few protected areas in Kenya and in Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda. They are in trouble.

The overall population of giraffes have dropped an estimated 30 percent, in the past decade, to fewer than 100,000 in all of Africa.

On a positive note, the discovery of large antelope herds in Southern Sudan, historically the very center of giraffe evolution, has caused some hope that hidden pockets of giraffe, in good numbers, may also exist there. Because of political difficulties and war, Southern Sudan was off limits to conservationists for twenty years, until recently, when Wildlife Conservation Society efforts documented the species was still there with their count of 400 giraffes.

The following is the abstract from BMC Biology:

Background

A central question in the evolutionary diversification of large, widespread, mobile mammals is how substantial differentiation can arise, particularly in the absence of topographic or habitat barriers to dispersal. All extant giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) are currently considered to represent a single species classified into multiple subspecies. However, geographic variation in traits such as pelage pattern is clearly evident across the range in sub-Saharan Africa and abrupt transition zones between different pelage types are typically not associated with extrinsic barriers to gene flow, suggesting reproductive isolation.

Results

By analyzing mitochondrial DNA sequences and nuclear microsatellite loci, we show that there are at least six genealogically distinct lineages of giraffe in Africa, with little evidence of interbreeding between them. Some of these lineages appear to be maintained in the absence of contemporary barriers to gene flow, possibly by differences in reproductive timing or pelage-based assortative mating, suggesting that populations usually recognized as subspecies may potentially represent different species. Further, five of the six putative lineages also contain genetically discrete populations, yielding at least 11 genetically distinct populations.

Conclusions

Such extreme genetic subdivision within a large vertebrate with high dispersal capabilities is unprecedented and exceeds that of any other large African mammal. Our results have significant implications for giraffe conservation, and imply separate in-situ and ex-situ management, not only of pelage morphs, but also of local populations.“Extensive population genetic structure in the giraffe,” by David M Brown, Rick A Brenneman, Klaus-Peter Koepfli, John P Pollinger, Borja Mila, Nicholas J Georgiadis, Edward E Louis Jr, Gregory F Grether, David K Jacobs and Robert K Wayne, BMC Biology 2007, 5:57doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-57; published 21 December 2007.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, New Species, Replica Cryptia