July 7, 2008

Eric Guiler. Courtesy of Chris Rehberg.

Tasmania’s and probably the world’s leading authority on Thylacines, Eric Guiler, has died.

Dr. Eric Guiler, 85, died on Thursday, July 3, 2008, after six years of ill-health following a stroke. His friends are amazed he survived for this length of time, as the word from Australia and Tasmania immediately after his stroke was that he was “near death.”

A little known fact, shared among a few cryptozoologists at the time, is that Guiler suffered his last stroke while out in the bush looking for Thylacine signs. It was feared he was going to die in the field. He had to be carried out over rough terrain to get him help.

Guiler, who was known as Mr. Thylacine, spent much of his life researching the species, Thylacinus cynocephalus (also called Thylacines, Tasmanian Tigers and Tassies). He mounted several major government-backed expeditions in the 1950s and 1960s to search for the elusive Thylacines.

At a time when many marsupials were considered pests, Dr. Guiler launched scientific research into them.

Guiler led quests for evidence of Thylacines, finding tracks, hairs and scats which were donated to the Tasmanian Museum and Art gallery and still form the basis of research and DNA studies.

The Tasmanian professor was an early public critic of the museum’s cloning project – at one point, he called its proponents “bloody idiots.”

For Dr. Guiler, the larger question had always been whether the Thylacine still exists in the wild in Tasmania (and to a lesser extent, in western Australia). Guiler was convinced the Thylacine survived beyond its official extinction date of 1936. This came to a head when he interviewed elderly opossum trappers who confessed to snaring Thylacines through at least the 1950s, though they got rid of the carcasses for fear of prosecution.

Guiler’s attention turned to the Thylacine in 1952 when it was apparent that nothing was being done about what appeared to be this already rare animal.

Eric Guiler. Courtesy of Paul Cropper and Tony Healy.

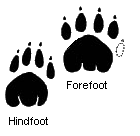

In 1957, in his role as a zoologist and chairman of the Animals and Birds Protection Board, Guiler went to Broadmarsh, Tasmania, to investigate the killing of some sheep by an unknown predator. Tracks were found that were identified as Thylacine prints. But no Thylacines were found.

Several more Thylacine expeditions followed between 1957 and 1966. In 1959, Eric Guiler conducted a search in Tasmania’s far north-west, an area which produced many finds of what appeared to be Thylacine footprints (identification drawing, below).

In August of 1961, when an animal was found going for bait from Bill Morrison’s and Laurie Thompson’s fishing camp at Sandy Cape, Tasmania, one night, Thompson bludgeoned the animal with a stick. The next morning, they found a dead young Thylacine outside but it was gone when they returned to camp the following evening. However, the government was so encouraged by the report, Guiler received $2000 to set 700 snares along a 16 km line at Green’s Creek in the Sandy Cape area and another 800 snares at Woolrich, a hotbed of sightings, tracks, and scats since 1956. By the end of 1963, Guiler’s search had found no evidence. His trapping program at Balfour, begun in 1964, also failed in producing new convincing evidence.

His expeditions generally discovered more footprints and, even if in the absence of tracks, collected more credible accounts of sightings from the local residents.

Enhancing a technique only just beginning in those days, Guiler set up his own hidden camera operation in the 1970s-1980s, but his attempts to capture a living Thylacine on film frustratingly ended without positive results.

Guiler, who was still going out into the field late in his life, constantly collected eyewitness accounts of encounters with the animals, peaking somewhat in the 1970s and 1980s. Sightings of Thylacines, Guiler found, were more frequent than known, like in March 1982, when a Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife ranger turned on his spotlight to see a strange animal about 20 feet away. The ranger reported what he saw was a Thylacine, “an adult male in excellent condition, with 12 black stripes on a sandy coat.” The creature quickly ran off into the nearby brush.

But Guiler’s hunt for the last few Thylacines was fading late in the 20th century, and his thoughts about how to conserve them were wrapped up in the fact this was indeed a mysterious animal. Before his stroke, he said: “There’s nothing you can do. You’ve got an animal about whose behavior we know virtually nothing, about whose movements we know nothing, about whose general physiology we know nothing. We know so little about it, it’s impossible to devise a management plan. We don’t even know where the damned things are living. How do you devise a management plan for something like that?”

Near the end, facing his own personal extinction, Guiler had almost given up any last hopes for the continued survival of the Tasmanian Tigers, and certainly for him, the quest had run its course and was over.

Guiler was born and educated in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He served in the British Army in World War II in Tunisia. He moved to Tasmania in 1947, where he took up a lectureship at the University of Tasmania, gaining a Ph. D. in Marine Biology. Today, the University of Tasmania offers three wildlife scholarships in his honor, under his name.

Since his retirement in 1981, he wrote often about the cryptid Tassies, and appeared on many television programs concerning the Thylacine. Dr. Guiler is the author of two books regarded as definitive works on Thylacines – The Tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger (Oxford University Press, 1984) and, with P. Godard, Tasmanian Tiger, A Lesson to Be Learnt (Abrolhos Publishing, 1998).

A great friend of cryptozoology has passed away, and our deep condolences go out to his family and all his colleagues and research associates in Tasmania, New Zealand, and Australia. He will be missed.

Sources: Personal communications via Debbie Hynes, Chris Rehberg, and Paul Cropper; International Cryptozoology Museum archives; “Leading thylacine researcher dies,” Mercury, July 5, 008; When Light Meets Dark.

By pure coincidence, the day before Eric Guiler died, I posted “In Search of Thylacine Replicas.” Well, at least it was July 2nd here, but I might have already been July 3rd in Tasmania. Humm.

Jeff H. Johnston painted museum-quality replica of a Thylacine.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Men in Cryptozoology, Obituaries, Thylacine