February 26, 2008

Today, I received directly from Japan, for the museum, the above shown replica of the Iriomote wildcat (Prionailurus iriomotensis), a classic animal of discovery for cryptozoology. It may be only a minor figurine at 2.5 inches long to some, but I find it significant that such care has been bestowed onto this important replica. A mere three decades ago, this cat found itself moving from the world of being a cryptid to a felid zoological reality.

The Iriomote wildcat remains a mysterious species, even now, years after its discovery, as evidenced in this recent essay below.

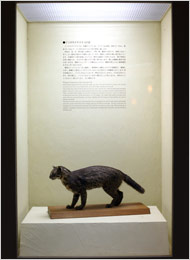

Unlike this stuffed Iriomote wildcat at a wildlife conservation center, live specimens are elusive and seldom seen. Photo by Ko Sasaki.

To protect the cat, a sign and a rumble strip alert drivers to slow down at a place where the animal is known to cross. Photo by Ko Sasaki.

An endangered species of wildcat survives only on Iriomote, a tiny, mist-shrouded Japanese island.

As a Japanese Island Grows Less Remote, a Wildcat Grows More Endangered By Noimitsu Onishi, The New York Times

Iriomote Island, Japan — The Iriomote wildcat is said to have roamed this small, subtropical island in the East China Sea for 200,000 years, but proved so elusive that it was not discovered until 1967. To this day, many islanders have never seen the wildcat, and some even stubbornly deny its existence.

One of the world’s rarest wildcats, it survives only here on Iriomote, one of Japan’s most far-flung islands. Almost indistinguishable from a house cat, the Iriomote wildcat is believed to be related to a leopard cat found on the Asian continent, to which this island was once linked.

In a nation where pork-barrel politics have paved over the country and dotted it with airports, Iriomote (pronounced ee-ree-o-mo-teh) can be reached only after a 35-minute ferry ride from neighboring Ishigaki Island and has a single main road hugging just half its coastline. Iriomote’s mist-shrouded, mountainous interior, blanketed by primeval forests and laced with mangrove-lined rivers, remains almost as impenetrable as ever.

Still, residents and tourists have increased in number in recent years, drawn by the island’s wilderness and by the wildcat itself, known here as the “mountain cat.” The encroaching development has added urgency to efforts to save the wildcat after Japan’s environmental authorities last year raised it one notch on a list of endangered species.

Researchers completing a census worry that the wildcat’s population has fallen below the 100 estimated more than a decade ago.

“It’s facing its biggest crisis ever,” said Masako Izawa, a wildcat expert at the University of the Ryukyus on Okinawa’s main island. Like other researchers, Ms. Izawa, 53, has spent years studying the animal without actually being able to see it, relying instead on photographs, videos and other secondhand evidence.

Though the wildcat is seldom spotted, its presence is felt everywhere on this island, including on buses, in restaurants and on bridges, all featuring images or sculptures of the animal. Signs on the island’s single main road, warning of wildcat crossings, are ubiquitous and manifold, vastly outnumbering cautionary road signs where children cross.

“Watch out for Iriomote mountain cats crossing,” reads one road sign with a drawing of the mottled wildcat. Others show a drawing of a leaping wildcat or a photograph with exhortations to “drive slowly, Iriomote.” Yet another type of road sign, with two red lights on top, displays a rudimentary, though instantly identifiable, sketch of the wildcat, with the plea that “there are mountain cats ahead — watch out!!”

With an average of three wildcats ending up as roadkill every year, the island’s two-lane main road — progressively widened to accommodate the increasing number of cars — has emerged as the main threat to the wildcat. The road meanders through the island’s inhabited lowlands, which happen to be the wildcats’ preferred territory.

The authorities have devised elaborate methods to help the wildcat cross the road unscathed. Even as the road has been widened for greater traffic and speed, new rumble strips called “zebra zones” induce drivers to slow down and alert wildcats to oncoming cars.

Eighty-five “eco roads,” or underpasses for animals, have been dug under the main road. Surveillance cameras set up at 19 of the underpasses confirm that wildcats are using them, though perhaps not as frequently as other animals, and perhaps not enough to offset other changes in recent years.

With most of Iriomote’s 110 square miles inaccessible to human beings, only 2,325 people live here. But even as the rest of rural Japan’s population has been decimated in the last decade, Iriomote’s rose 22 percent. What is more, the number of tourists surged by 33 percent in the past five years, reaching 405,646 last year.

“Human traffic into areas that human beings did not enter before is getting heavier,” said Chieko Matsumoto, 62, the leader of a private group that seeks to control the population of stray house cats, which can transmit diseases to the wildcat.

In its long history here, the wildcat has stood at the top of the food chain in a small, fragile ecosystem whose isolation and rich biodiversity have earned Iriomote comparisons to the Galápagos. On an island without mice, the wildcat eats everything from wild boar to shrimp.

“Many believe that Iriomote is too small an island to support the presence of such a carnivorous animal,” said Maki Okamura, a wildcat expert at the Iriomote Wildlife Conservation Center. “So it’s widely regarded as nothing short of a miracle that the wildcat has been able to survive as a species on this island for 200,000 years.”

Human traces have been found here dating back centuries. Coal mining brought settlers here a century ago, though malaria kept the population low. Today’s old-timers, like Kimiaki Fujiwara, 78, came here as children and tend to be skeptical of all the attention the wildcat is getting.

Mr. Fujiwara said he had never seen a wildcat in his 68 years here and actually doubted its existence. “I think they’re just house cats that ran away and are living in the mountains,” he said.

“I guess it’s all right to protect wildcats or whatever, but I’d also like them to protect people,” he said, adding that most of his neighbors lived on pensions. He was expressing an opinion often heard in his neighborhood on the island’s northern coast.

The old-timers’ ambivalence, and sometimes outright antipathy, toward the wildcats can be traced to a visit by a German feline expert shortly after the discovery of the wildcats in 1967. To save the wildcat, the German suggested forcing all humans off Iriomote.

The more recent tourist boom has exposed fresh tensions. Longtime residents tend to be farmers and have little interest in the wildcat. Newcomers operate tourist-related businesses that depend in part on the wildcat’s survival but may also threaten it.

As an indication of the fragility of the balance, a male wildcat crossing the island’s main road was hit and killed by a car on a rainy evening a few days after the interview with Ms. Okamura. The center had tracked the wildcat for three years and named him Googoo.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Classic Animals of Discovery, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Mystery Cats, Replica Cryptia