January 4, 2013

I am saddened to hear the news that the world’s foremost Mongolian Death Worm researcher, Ivan Mackerle died on, apparently, January 3, 2013. The following is a rough translation from the Czech by Dmitry Pikulov):

+++

Zemřel Ivan Mackerle

03. 01. 2013 PAVEL MIŠKOVSKÝ ŽÁDNÉ KOMENTÁŘE

Po delší nemoci ve čtvrtek 3. ledna 2013 zemřel publicista a záhadolog Ivan Mackerle. Byl dobrodruhem a poctivým badatelem ze staré školy, o svých objevech napsal mnoho knih, článků a natočil několik dokumentů. V březnu by oslavil 71 let…

Pro řadu lidí v projektu Záře zůstane nezapomenutelným kamarádem a vzorem.

Ivane, ať tam nahoře vyřešíš každou záhadu…

+++++

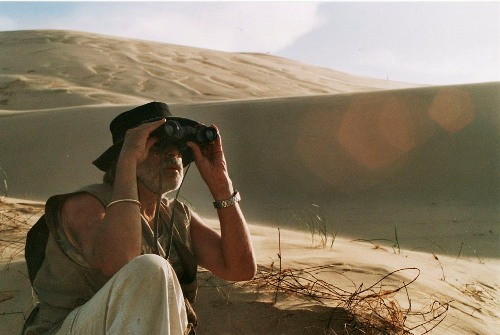

Photo courtesy of Ivan Mackerle and Prague Post

For the past 40 plus years, Ivan Mackerle, as a self-made cryptozoologist, traveled the world searching for creatures that defied documenting. Mackerle spent his life savings outfitting expeditions, from the deserts of Asia to Loch Ness, from Papua New Guinea as well as other locations.

Illustration by Jiri Zacek/courtesy of Ivan Mackerle

His three trips to the Gobi Desert failed to unearth any scientific proof of the death worm allghoi khorkhoi.

In 2007, this was written about the cryptozoologist:

Wherever and whenever it was, Ivan Mackerle, the noted Czech adventurer and seeker of apocryphal creatures, has finally found a sense of skepticism.

Maybe he found it in the Gobi desert as his explosives concussed beneath the dunes, sussing out a legendary worm. Or perhaps it was while hacking through the thick of Madagascar’s jungles in search of a man-eating death blossom, or scuba diving beneath the blue waters of a remote Micronesian island, sure he’d discover a mausoleum filled with platinum coffins.

Over the past 30 years, Mackerle, 65, and his small band of friends have traveled across the world in search of legendary animals — cryptozoology, the field is called — and occult sites, lost treasures and hidden kingdoms buried deep within the earth’s crust.

With the dedication of a child on an extended summer holiday, Mackerle has let nothing stand in the way of his journeys — not the former communist government, not social norms, limited resources, or, most perilously, the stubborn refusal of monsters to exist.

“I sacrifice everything for this,” he says while recounting his trips, leafing through the photos and maps that pepper a book he’s written on the subject. He’s dressed in the self-conscious clothing of a field man, all khaki with multi pocketed vest. His gray hair is tousled and his round sunglasses tinted red.

“Most people, when they’re adults, they marry and their lives begin,” he says, with a hint of wistfulness. “They have children and make money, they have their careers. But I wanted to stay in my dreams, with these adventures.”

Occupied thoughts

Those dreams began early, during his childhood in Plzenˇ, west Bohemia. Mackerle was 3 when the Americans liberated the city at the end of World War II. “When I was young in school they taught us that only the Russians liberated us,” he says. “I had trouble with that, I said. I have photos from when I was a little boy with American GIs and their jeeps.”

That’s when Mackerle began to wonder if explanations for dissonance in the world existed beyond the party line.

During his youth, Mackerle immersed himself in books on mysteries and exploration, such as those of the Russian paleontologist and sci-fi writer Ivan Yefremov or the American investigator of the unexplained, Charles Fort, whom the British writer Colin Wilson has described as the “patron saint of cranks.” (Fort’s work has inspired a whole cottage industry, 75 years after his death; his name has even become an adjective describing anomalous phenomena — Fortean.)

In this pulp from an earlier era, Mackerle found his life’s calling. And throughout his training as an automotive engineer — following his father’s footsteps — and a nascent career as a hydraulics designer, he never escaped his siren’s call.

“I didn’t only want to read about [mysteries],” he says “I wanted to search, to try and find out if it was true or only fiction.”

Saving up his money, in his early 20s Mackerle bought and refurbished a German amphibious jeep from World War II. “It was the ideal car for expeditions,” he says. “It has four-wheel drive; it can go in the water.” And with that, he and two friends were off on their first expedition outside the country, to Transylvania. They were going to find Dracula’s castle.

Using Bram Stoker’s book as their guide, they drove in the footsteps of the novel’s hero, Abraham van Helsing. They knew Stoker had never been to the region, but, given the book’s origins in local folklore, they held out the hope of discovery. They finally found some stones and walls. “We thought it was Dracula’s castle,” Mackerle says wryly, while acknowledging that many now believe that Vlad the Impaler, whose Bran Castle is on the other side of Transylvania, was the source of Stoker’s inspiration.

Still, the trip was enough of a success to launch a much larger expedition: Mackerle wanted to cross the Iron Curtain and go up into Scotland in search of the Loch Ness Monster. He was repeatedly frustrated in his petitions to cross the border, but his team finally got the go-ahead after Mackerle wrote an impassioned letter to the state about his research. It was 1977 and he was 25 years old.

Loch Ness changed everything. As with Mackerle’s future journeys, his team had no financial backing, so their survey required ingenuity ? they couldn’t afford a boat, and instead jury-rigged a raft out of a plastic pool, tractor tire tubes and a metallic frame. “In the floor were small windows where we could look through to the water,” he says. “But we didn’t see the monster.”

The team of young Czechs couldn’t stay long at Loch Ness — Mackerle only had three weeks’ vacation from work — but they were there long enough to meet Robert Rines, an American lawyer and inventor who had a fleet of specialized underwater photographic and ultrasound equipment searching for Nellie. Mackerle was impressed, and when he returned to the Czech Republic, he began to give presentations at clubs and schools on his adventure in the West and the marvelous investigations of Rines.

“It was very popular,” he says. “The government didn’t want me to speak about this mystery because it was not materialistic. … Because these lectures were so popular, I quit my job and started to freelance. It was very unusual at the time.”

The Czechoslovak state did not allow Mackerle to replicate his trip to Loch Ness, so he had to satisfy himself investigating domestic mysteries, like Prague’s golem. It was frustrating. Even fellow communist states, such as Mongolia, were cold to his entreaties. And Mongolia’s Gobi desert held particular fascination for Mackerle, as it was the rumored home of a legendary and deadly worm that had gripped his imagination since childhood: the Allghoi khorkhoi.

Explosions in the desert

Mackerle first read about the worm as a boy in the stories of Yefremov, the Russian paleontologist. Yefremov wrote that the worm, which resembled a bloody intestine, could grow to the length of a small man and could mysteriously kill people at great distance, possibly with poison or electricity. Poor Mongolian villagers could only cower in their yurts in fear.

“I thought it was only science fiction,” Mackerle says. “But when I was in university, we had a Mongolian student in our class. I asked him, ‘Do you know what this is, the Allghoi khorkhoi?’ I was waiting for him to start laughing, to say that’s nothing. But he leaned in, like he had a secret, and said, ‘I know it. It is a very strange creature.’”

After that, Mackerle knew he had to search for the elusive worm. But it wasn’t until the Velvet Revolution — he was a face in the crowd on Wenceslas Square — that the trip could happen. By the next year, 1990, Mackerle and his two loyal companions, Jirˇí Skupien and Jarda Prokopec, were in the southern Gobi desert.

In three trips to Mongolia (he returned in 1992 and 2004), Mackerle never found the Allghoi khorkhoi. But he traveled the whole of the Gobi, drinking fermented milk with herdsmen and swapping hearsay and dirty stories. Once, their guide said he knew of a young boy killed by the worm. On his last expedition to Mongolia, Mackerle brought an ultralight plane with a camera that scanned the dunes for signs of the Allghoi khorkhoi, which would be displaced by explosions set off beneath the sand. Still no luck.

Mongolia and Mackerle’s subsequent expeditions over the past 15 years to Australia, Micronesia, Madagascar, Siberia and elsewhere share one similarity: the pang of failing to unmask the mystery of a paranormal site or discover a new and fantastic species. But that does not mean creatures such as the Allghoi khorkhoi should be written off as tall tales, Mackerle says. After all, such stories led scientists to discover the Komodo dragon and mountain gorilla.

Until they’re documented, he says, about his legendary beasts, “Ordinary biologists and zoologists don’t believe they can exist. For them it’s not a science, it’s a pseudoscience.”

But some cryptozoologists are well respected, such as Roy P. Mackal, who hunts for the Loch Ness Monster, or Dr. Karl Shuker. “They are scientists, and they are looking for creatures. They think it is possible to find, somewhere out there, animals that aren’t yet known.”

That possibility is animating, and when you talk with Mackerle, it is infectious. He lives in a world of potential, of what still could be, the hope that everything hasn’t been explained. Mystery exists.

That’s not to say his enthusiasm hasn’t been tempered by experience. After three trips, he has no desire to go back to Mongolia. If there’s a death worm, someone else will have to find it.

“Today, I’m more skeptical about everything,” he says. “But I have had strange experiences that are hard to explain. So I’m open-minded, even if I’m not as enthusiastic after all I’ve seen.”

So why continue with his expeditions, with little hope of actual discovery?

“Mainly, it’s for love of adventure,” he says. “Naturally I’d like to make a discovery, but it’s very difficult to find something new. But still, it’s exciting to go through the countryside with machetes, to drive through the desert meeting people to talk about mysteries.”

Dinosaur calls

Mackerle continues to be self-employed, giving lectures and saving every penny made from his book, Cesty za prˇísˇerami a dobrodruzˇstvím (“Quests for Monsters and Adventure”), and his regular column investigating mysteries for Mladá fronta Plus, a weekly supplement to the daily newspaper. Most recently, he’s been exploring the possibility of premature burial — a fear enough people take seriously to fuel a small industry in modified coffins with phones and air supplies.

The column has sapped some of Mackerle’s time from planning his next expedition, but in this planning he has support: his son, Danny. (Mackerle has been married since his 20s, but his presumably patient wife has never joined the expeditions, which remain very much a boys’ club.) While Mackerle would seem a dream father for any boy, for a long time Danny was focused on anything but adventure travel. As a teen he was more interested in music. But ever since he joined Mackerle on the Madagascar trip, Danny, now 44, has become the driving force of the expeditions.

“He says, ‘Daddy, we must prepare another expedition,’ ” says Mackerle. And so, despite Mackerle’s desire to lengthen his breaks between adventures, another expedition is in the works for this fall, to Papua New Guinea.

Reports have surfaced of Amazonian cannibals there, he says. “Women walking naked through the jungle with spears.” In order to repopulate, Mackerle adds, “Sometimes they grab men from villages. … Then the men are ritually killed and eaten.”

A military officer from Jakarta has investigated the reports but failed to find any Amazons. It’s likely a myth, Mackerle says with a youthful snicker. “But it’s very good for the newspaper, a good story with all the sex and nudity.”

The Amazons are a pretext, anyway. There’s another reason Mackerle is going to Papua New Guinea: Unconfirmed reports of pterodactyls soaring through the jungle’s canopy. Their skin is fluorescent, they say; as the dinosaurs whisper through the air at night, they glow.By Paul Voosen, Staff Writer, The Prague Post, May 16, 2007.

Artist Rob Farrier’s Mongolian Death Worm illustration.

Born in March 1942 in Pilsen (Czech Republic). His father Juliuswas noted automotive constructor and so in the childhood Ivan changed residence as his father changed ocupation. At the age of three he moved to Prague, at his five to Koprivnice in Moravia and at sixteen back to Prague, where he lives untill this days. In his childhood he was influenced by the adventurous books by Jaroslav Foglar, and by magazines for dhildern “Vpred” and “Junak” which he had to borow secretly. These reading was illegal at that time. Communist regime at that time alllowed only “socialistic” books and magazines. Despite this he with his friends estabilished boyish club on the lines of the literaly boys “Fast arrows”, and searched boyish adventures.

Later he turned his interest to zoology and electronics but at the end he studied up CVUT University in Prague, faculty of mechanical engeneering, motorcar specialization. In his twenty he marryied Ivona Palickova and his son Danny was born. After finishing school he worked as a designer and then as a superviser in General directory of automotiv industry. In his spare time he push ahead an amaterous films and he shot adventurous movies, initially on 8 mm format, later on 16 mm format.

But mainly he has been passionately interested in learning about all sorts of mysterious and unrevealed phenomena dissclaimed by the official science. Initially he studyied and gathered them up only, later he started to investigate them himself. With his former colleague Michal Brumlik they verified the claims about strange phenomena and hauntings in the old castles including poltergeist cases, strictly concealed by former communistic regime. He became to be known to Czech public thanks to his lectures and audiovisual performances “Beautiful mysteries of our planet”, whitch performed with Brumlik all around Czech republic in period 1980 till 1990, and captured interest of public for still unsolved mysteries. After fall of the Totalitarian Communist regime in 1989 and with begining of freedom, he started to organise expeditions to diferent parts of the World in the search for monsters and mysteries. The range of his interest is wide from cryptozoology over forteana, historical mysteries to paranormal phenomena and parapsychology. He makes documentary films about his expeditions. In 1998 till 2000 he acted as consultant for TV series Záhady a mystéria (Enigmas and mysteries) in Television Prima. in the years1998 till 2002.

In the years 1998 till 2002 he has been a chairman of editorial council of Czech magazine “Fantastická fakta” (Fantastic Facts) writting about strange phenomena. Currently he is explorer and freelance publicist and writer about mysteries and forteana phenomena. He has written a number of books and is a longstanding contributor to many Czech magazines. Some of his articles was published also in FATE magazine or ForteanTimes magazine. Outside mysteries Ivan Mackerle´s interest include historical military vehicles and with his son Danny, driving their amphibious Volkswagen 166 (Schwimmwagen) from 2.World War.

Source: Ivan Mackerle

Deep appreciation to Karl Shuker, who shared the news of Ivan’s passing. Article and images used with the permission of Paul Voosen. Thank you, Paul! Appreciation to Rob Farrier too.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Megafauna, Men in Cryptozoology, Obituaries