Auroch (Bos primigenius).

September 29, 2010

Today, I introduce another guest blog from German cryptozoologist Markus Felix Bühler, the author of the cryptozoology book, Die Insel des Grauens…

Europe’s Lost Megafauna: Part I – The Ungulates

by Markus Felix Bühler

If people hear the word megafauna, they generally associate it with prehistoric animals, but even today true megafauna is existing. Some continents like Africa and Asia have maintained nearly all of their native species of large animals during the last millenia. Other continents like North America and especially South America lost most of their megafauna around 10,000 years ago, but there are still very large areas with low population and a comparably healthy nature. Australia already lost nearly all large animals some ten thousands of years ago. In Europe, many of the most impressive members of the megafauna like mammoths, wooly rhinos or cave lions became extinct during prehistoric times, but several huge-grown species survived into more historical times. But as a result of excessive hunting, deforestation and land reclamation for agriculture and settlement, even the last surviving members of the European Megafauna suffered more and more.

In this article I want to deal with these once common animals, not only to show non-European readers how diverse and fascinating the European fauna once was and in some regions still is, but also of course for European readers, who will possibly be surprised to learn what amazing animals were once common in their home land. I am mainly describing the situation in Central Europe, not only because I am living at Germany and most familiar with the wildlife situation here, but also because this region has especially drastically suffered from species extinction, more than most other regions. A main reason is the long history of this region, in which humans dramatically altered the landscape. Today it is also one of the most densely populated and most industrialized parts of the world, and only very little untouched nature remained.

There are several definitions for the term “Megafauna,” for example only animals of more than 45 kg. Other definitions are lesser rigorous, and also include smaller animals. I will use the term comparably loosely, to include also some smaller yet still noteworthy species. Of course it will not be possible to go too much into the details of the local or in some cases even global extinctions, historical notes and resettlements in modern times. I have to apologize that I won’t list every single species which could be noted, especially among those which are marine animals, but I tried to register at least the most important ones.

I will begin with the most impressive ones, the large ungulates. It is hard to imagine that in some regions of central Europe not even that long ago, several very large artiodactyls were living. The famous Nibelungen has a passage in which Sigurd’s kill of a hunt is listed. According to the rhymes he killed a wisent, a moose, four aurochs, several male red deers and hinds, a big wild boar and some other animal, which are not that easy to identify. One of them is the “halpsvuol,” which could be possibly a subadult wild boar or a pregnant sow. Among the killed animals also a lion is listed, but it seems that this was not the term of the original version, but a later replacement for a bear. The third mysterious animal, the “Schelch” has already gained some cryptozoological attention, and was even supposed to be a surviving Megaloceros. To say it mildly, this is highly unprobable. But I don’t want to deal with this more obscure creatures, but with those whose identity is clear.

Auroch (Bos primigenius).

Without doubt, the aurochs was one of the most impressive animals of Europe. This huge wild cattle surpassed most modern domestic breeds in size and strength. Bulls stood around 1.70-1.90 m at the shoulder and weighed up to 1000 kg. They had long limbs and were very well-muscled. Their heads were much longer than those of most modern cattle breeds, and they showed a significiant sexual dimophism in size and colour. Aurochs bulls had also very strong black-tiped horns, which were already among Germanics at Julius Ceasar’s time highly prized hunting trophies. The colour of the aurochs variated among its huge geographical range, but at Europe the bulls were in general of nearly black dark colour, with lighter markings arount the muzzle, the eyes, the front and the inside of the legs legs. A typical trait was the greyish dorsal stripe which did run down the whole back. The cows in contrast were of a dark reddish-brown colour, and the dorsal line was also more reddish-brown.

Auroch (Bos primigenius).

The Aurochs (Bos primigenius) was once distributed over a very large area, ranging from north to south Europe, Russia, the middle-East and even parts of Asia and North Africa, but it was exterminated in most of this regions during antique times. Some old depitctions like the wild bulls on the Ishtar gate, which is in cryptozoological literature mainly famous for its depictions of the dragon-like Sirrush, show a southern subspecies of the Aurochs. There are also old descriptions and depictions of aurochs-hunts from this region. Among all game animals it was always one of the most prized ones, and among the prefered game-animals of kings and aristocrats from the Assyric ruler Tiglatpileser I to Charlemagne. Already during early Medieval times, the aurochs was extinct in nearly all of its original habitats, except some parts of continental Europe and Russia. In Germany the last ones were killed in the second half of the 15th century, in Eastern Europe they survived some time longer. At the beginning of the 17th century there was only a small handfull of this magnificient animals left within the forest of Jactorow, where the last cow died in 1627.

Wisent (Bison bonasus).

But the Aurochs was not the only European bovine; there was also a second one, the wisent. The wisent (Bison bonasus) looks very similar to the bison (Bison bison) of the North American continent. In contrast to the bison which mainly lives at big herds on the open plains, the wisent inhabits mainly woods and lives in small herds of normally only 12-20 animals. Similar to the aurochs, the wisent was also hunted to extinction in most of its natural habitat, and its history had nearly gone a similarly tragical way. At the 16th century it was already extinct in central Europe, but survived in Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe and Russia. The last ones were protected game animals for the supreme aristocrats, otherwise they had surely disappeared completely. But as a result of poachery and epidemics, the remaining populations nearly vanished. Only as a result of intensive breeding the species was rescued. Today there are only very few regions in which wisents live again in small wild populations, and given the huge size and potential danger of this spezies, there are only very few regions left which would be still suitable for wild wisents.

Moose (Alces alces)

Besides aurochs and wisent, the moose was the next largest terrestrial animal. Today the moose is in Europe mainly associated with Scandinavia, and it is hard to imagine that its distribution was much wider in earlier times. It disappeared in middle-Europe during the early Middle Ages, but interestingly up until today the names of several villages and towns remind of the former existance of mooses. For example, the town Elchingen or Ellwangen (what translates in old-fashioned German as “moose-meadow”). The modern German word for moose is “Elch,” but in earlier times it was also called “Elen.” Today there are no more populations of moose in central Europe at all, only occasionally single individuals from Poland are found as vagrants in some regions, but it is very improbable that it will ever again establish populations in more western areas.

Without doubt the moose was the most impressive deer which lived during historical times at continental Europe, but there were also two other species of deer. One of them is the small roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), a species which is actually today more numerous than in earlier times. In contrast the big red deer (Cervus elephus) greatly suffered from overhunting, especially during the middle of the 19th century. But at least this impressive species managed to survive as the biggest remaining megafauna-species and became again common in some areas.

Another even-toed ungulate which was once very common in the alpine regions of Europe is the ibex (Capra ibex). In 1820, there were only 100 remaining specimens, but as a result of strict hunting restrictions and captive breeding, the species has recovered comparably well, and the complete population consits now of around 30,000-40,000 specimens at the European Alps. There is also another mainly alpine European ungulate, the chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), which also highly suffered from overhunting, but by far not to the same degree is the ibex, and the modern population counts around 500,000 specimens at Europe. So there is luckily not much more to say about this animal.

Wild boar (Sus scrofa).

In modern times the wild boars (Sus scrofa) are in many regions again a very common part of the Central-European wildlife, even if they are in general only very rarely seen. I often walk in the woods, but I have only once seen two wild boars in the wild, and only because they were running away from a hunt. Today the wild boars are so abundant in some regions that they are seen as a pest species, which can cause great damage to farmland. The absence of natural predators like wolves, additional sources of food from agriculture and especially warm winters has caused a massive increase of the wild boar populations, and they repopulated many regions in which they were formerly extinct. Given the fact how much wild boars there are today, it is hard to believe that only a century ago they were actually exterminated in many regions. But at the end, the wild boar was similar to the roe deer among the only successful survivors of the former megafauna.

Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalski).

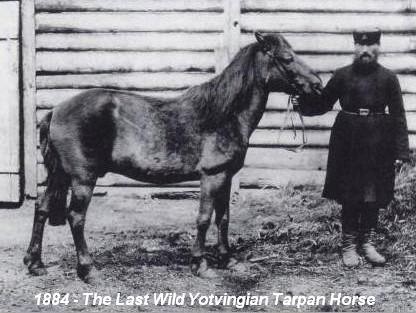

But there were many other species which had lesser luck. Besides the already mentioned even-toed ungulates, there were also odd-toed ungulates in Europe, the wild horses. Today there are many regions on the world where feral horses are living, for example the mustangs of the United States. But they are all descendants of domesticated horses. The only surviving true wild horse of the world is the Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalski) of Mongolia, which was almost on the brink of extinction. In contrast to the wild horses of Asia, the European wild horse is now completely extinct. This wild horse was called the tarpan, and existed in two different subspecies, the forest-dwelling wood tarpan (Equus ferus sylvaticus) of Central and Eastern Europe, and the steppe tarpan, which lived in the open steppes of southern Russia. The tarpan looked similar to the Przewalski horse, was rather small and sturdy, and had a greyish coat.

Tarpan.

Like most other large animals of Europe, the tarpan died out in many region comparably early, as a result of hunting and loss of natural habitat. The last remaining wild tarpans survived at some regions of Poland until the 18th century. The last ones were caught and lived in captivity up to the early 19th century, but in 1808 this last enclosure was shut for economical reasons and the remaining wild horses given to peasants. Today there are no more pure-breed tarpans, but it seems that in some local breeds genetic tarpan-heritage has survived, especially in the Polish konik-horse. This breed was also used in experiments in which it was tried to rebreed a tarpan-like horse.

Chamois.

Ibex.

Now we see that there was still a diverse and impressive ungulate fauna at postglacial Central Europe. There were aurochs and wisents, mooses, red deers, roe deers, ibex, chamois, wild boars and tarpans. Of course not all of this animals lived everywhere or always at the same regions. Today only wild boars and roe deers are still or again abundant, red deers are still locally extinct in many regions, but have well recovered in many other areas. Chamois and ibex are restricted to some alpines regions, but far away from being really nummerous. Compared to the ancient ungulate-fauna, this is only a very poor relic. In some regions there are also non-native species, for example fallow deer (Dama dama), which was already introduced in some regions at medieval times, as well as some later introduced species like the asian Sika deer (Cervus nippon) are only comparably locally common.

This was the first part about the lost Central European Megafauna, the next part will mainly focus on carnivores.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Cryptomundo Exclusive, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Fossil Finds, Guest Blog, Megafauna