July 18, 2011

Tom Slick and O’Neil Ford. (Roy Stevens photo, Fortune, 1960)

Tom Slick, the great cryptozoological sponsor, seeker of the Abominable Snowmen of Nepal and the Sasquatch of the Pacific Northwest (for more details, please see Tom Slick: True Life Encounters in Cryptozoology), has left behind a legacy still able to be seen in San Antonio, Texas. Of course, well-known is Slick’s creation, the Southwest Research Institute.

Craig Woolheater and Loren Coleman are pictured at the entrance of one of Tom Slick’s SWRI sites in San Antonio.

Additionally, there remains today Tom Slick’s house in San Antonio, designed by a famed architect.

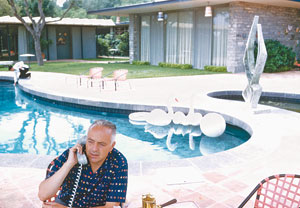

Tom Slick, poolside at his O’Neil Ford home, with Barbara Hepworth’s “Cantate Domino” in the background. (Roy Stevens photo, Fortune, 1960)

In 2009, at the McNay Art Museum, an art exhibition was held entitled “Tom Slick: International Art Collector.” In part of the description of the exhibition, there was a discussion of the architect behind Slick’s San Antonio house:

“In the late 1950s, [Tom Slick] worked with famed San Antonio architect O’Neil Ford on the design of an ultra-contemporary house that was constructed using the Youtz-Slick Lift-Slab method, a quick and inexpensive way to erect low-rise slab buildings Slick helped develop, which Ford also used in the construction of the Trinity University campus. Slick spent the last few years of his life filling the house with some of the best art of his time, including works by Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Isamu Noguchi, Georgia O’Keeffe and Pablo Picasso,” wrote Dan R. Goddard for Glasstire.

The Youtz-Slick Lift-Slab method was partially Tom Slick’s invention, and with great fanfare, when his home’s roof slab was lifted, Slick had a celebratory cocktail party on the slab as it was raised into place. For more details, please see Tom Slick: True Life Encounters in Cryptozoology.

Clemson University’s Johnstone Hall is one of the few places in the USA where the Youtz-Slick Lift-Slab is still visible. Erected in 1954, the Johnstone Hall complex design became a model for college dormitories, implementing a new raise-slab construction method, a practice which was featured in many architectural magazines at that time. This method – the Youtz-Slick “lift-slab” method – lifted reinforced concrete slabs onto columns with hydraulic jacks. These slabs weighed 224 tons and were nine inches thick, 122 feet long and 43 feet wide. Johnstone Hall was the largest building complex erected using this method. Johnstone was one of only three construction sites ever built (not including private homes) using this technique, and was the last one condemned, though there is one remaining that had not been demolished as of the spring of 2010.

Johnstone Hall, Clemson University.

The lift-slab construction was also used at The L’Ambiance Plaza in Connecticut, and the collapse of that structure was one of the worst disasters in modern Connecticut history. L’Ambiance Plaza was a 16-story residential project under construction in Bridgeport, Connecticut at the corner of Washington Avenue and Coleman Street. Its partially erect frame completely collapsed on April 23, 1987, killing 28 construction workers. Failure was possibly due to high concrete stresses on the floor slabs by the placement process resulting in cracking ending in a type of punch through failure. There was a school of thought that this accident was preventable and highlighted the deficiencies of the lift slab construction technique. This accident prompted a major nationwide federal investigation into this construction technique as well as a temporary moratorium of its use in Connecticut. Few architects will use the lift-slab method today, although this may have been an over-reaction to the L’Ambiance Plaza event.

In the 1950s, the design of Tom Slick’s private house was the responsibility of architect O’Neil Ford. O’Neil Ford (1905–1982) was a major regional architect of the mid-20th century in Texas and a leading architect of the American Southwest. He is considered one of the nation’s best unknown architects, and his designs merged the modernism of Europe with the indigenous qualities of early Texas architecture.

O’Neil was born in Pink Hill, Texas in 1905 but moved to Denton in 1917 after the death of his father. He enrolled in North Texas State Teachers College for two years, but financial burdens forced him to abandon his efforts of a formal education. Instead, he earned an architectural certificate by mail from the International Correspondence Schools of Scranton, Pennsylvania.

In 1926, he began a long partnership with regional architects and was first mentored by architect David R. Williams. Together they produced a number of fine regional houses of native brick, wood, and stone in north central Texas. He entered into private practice in 1934 and worked with a series of partners within the state of Texas beginning in 1936.

Ford was influenced by the tradition of the English Arts and Crafts Movement and the attempt to combine architecture and visual arts. As a strong preservationist, he helped launch Texas architecture on a new path by showing that its roots were deep and often beautiful. His well-crafted structures were composed of bricks, glass, wood, and were intimately tied to its setting. He enlisted his brother Lynn, a master carver and sculptor, to create custom doors, screens, and louvered grates.

Ford was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1960. He was appointed to the National Council on the Arts by President Lyndon B. Johnson, and in 1974 Ford himself was designated a National Historic Landmark by the Council (the only human to ever be given that title).

He resided in San Antonio until his death in 1982 at age 76. In 2001 Drawings were donated by his widow, Wanda Graham Ford, to the Alexander Architectural Archive at The University of Texas at Austin. The gift included 5,540 original architectural drawings, 5,484 prints, 40 presentation drawings, 39 presentation sketches, and 63 sheets of photographic materials.

O’Neil Ford designed several buildings in Denton, among them the Little Chapel in the Woods, renovations at the Emily Fowler Public Library, the Denton Civic Center, Denton’s City Hall and several buildings at The Selwyn School. Because his designs form much of Denton’s identity, a Texas historical marker honoring Ford was dedicated at the Emily Fowler Library in 2009.

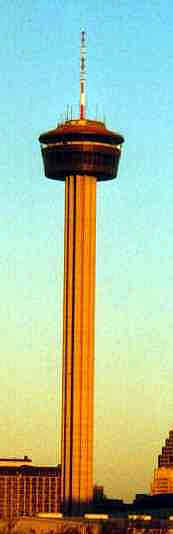

Later based in San Antonio, many of Ford’s works are found in that city (including the Tom Slick house). Some of them include the renovation of La Villita, the campus of Trinity University, the University of Texas at San Antonio campus, and the Tower of the Americas (shown above).

“Ford made preservation a cornerstone of his developments, even when it cost him business. Because of his stubborn opposition in the ’60s and ’70s to the North Expressway development, Ford’s firm never received another city contract while he was alive. His efforts to save the historic homes within the HemisFair ’68 grounds cost him his job as lead architect, although he was allowed to finish the Tower of the Americas,” wrote Elaine Wolff.

Other significant works include buildings at Skidmore College (shown above) and several facilities around the world designed for Texas Instruments. Shortly before his death, he completed the design of the building of the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville in the Texas Hill Country.

But Ford’s work with Tom Slick is remembered most by those interested in the cryptozoological legacy of the San Antonio explorer and seeker of new horizons in zoology.

Tom Slick Jr. at his O’Neil Ford home, with one of his Picasso items. (Roy Stevens photo, Fortune, 1960)

Tom Slick and friends at his home, with another Barbara Hepworth sculpture. (Roy Stevens photo, Fortune, 1960)

One of the additions to the new, larger International Cryptozoology Museum will be the enhancing of our exhibitions as they relate to the architecture and art related to Tom Slick and his times. Slick was ultra-contemporary, modernist, futurist, and radical, whether it was in his innovative ideas about cryptozoology and inventions or his concepts for business and world peace. This will soon be more directly reflected at the museum, when we are able to expand in the coming months.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Abominable Snowman, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Men in Cryptozoology, Pop Culture, Tom Slick, Yeti