September 21, 2007

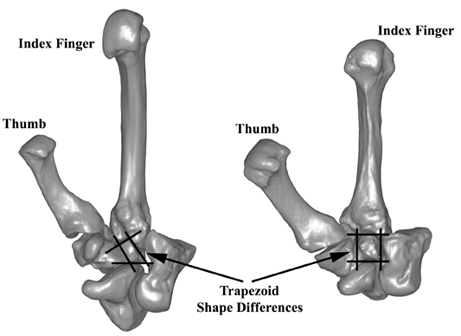

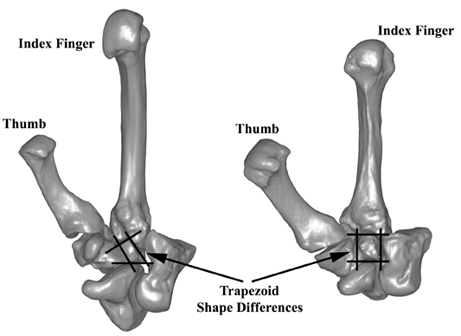

A comparison of wrist bones like those found in the “hobbit” human (left) and those of a modern human suggest that the diminutive hominin is a unique species, scientists say.

Image © Science

It is one of those busy news days, especially in terms of fossil updates.

The two big fossil discovery news items are primate and aves related, and of interest to Cryptomundo. One is the new Science report that a study of the wrist bones of Homo floresiensis confirms it is a new species, and not an abnormal human.

The other finding is that there were feathers on velociraptors.

Breaking fossil news on two fronts gives insights to the fact that all we know is merely part of yesterday’s unknowns.

The tiny, human-like creature living and using tools in Indonesia just 18,000 years ago really was a distinct species, not just a malformed modern human.

That is the clear implication of a new study of the so-called “hobbit”. It states that the creature had wrist bones almost identical to those found in early hominids and modern chimpanzees, and so must have diverged from the human lineage well before the origin of modern humans and Neanderthals.

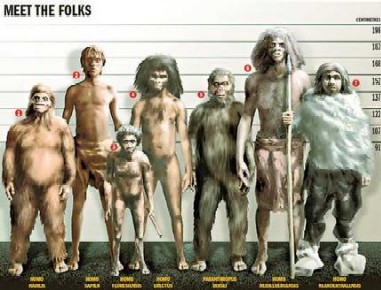

Palaeontologists have battled bitterly over the diminutive skeleton ever since its discoverers described it as a new species, Homo floresiensis, three years ago.

Its exceptionally tiny brain simply did not fit with the current understanding of human evolution, particularly since no other hominid fossils in the last 3 million years, and none outside of Africa, had such a small brain.

This dissonance led sceptics to argue that the hobbit must be merely a modern human with some form of microcephaly – a disorder which causes an abnormally small head and brain.

Most of the argument has centered on the skull, even though much of the rest of the skeleton was excavated at the same time. When Matthew Tocheri, a palaeoanthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, happened by chance to see casts of the specimen’s wrist bones, he knew they told an important story.

Ancient structure

Tocheri, an expert in the evolution of the human wrist, could see immediately that the hobbit’s wrist bones looked just like those of a chimpanzee, or an early hominid such as Australopithecus, and had none of the specialisations for grasping that are seen in the wrist bones of modern humans. A careful statistical comparison gave the same conclusion.

“The modern human wrist hasn’t looked like this for at least 800,000 years, and maybe much longer,” says Tocheri. “It was immediately apparent to me that the hobbit is the real deal.”

Developmental abnormalities such as microcephaly are unlikely to change the shape of the wrist bones, he adds, because the shape of these bones is laid down very early in development, long before the genes controlling growth rates become active.

Other soon-to-be-published studies of the hobbit’s foot bones, upper arm and shoulder also suggest that its anatomy differed from that of modern humans. “As you add these up, you do certainly get a picture of something distinct and not human,” says Chris Stringer, an authority on human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, UK.

However, Robert Martin, a primatologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, US, who is the leading advocate of the microcephaly explanation, remains unconvinced. No one has studied the wrist bones of microcephalic humans, he notes, so it is pure conjecture to say they would not look like the hobbit’s bones.Bob Holmes, Journal reference: Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1147143)

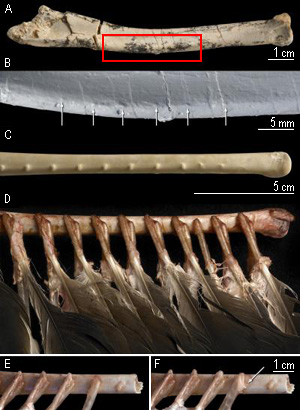

(A) View of right ulna of Velociraptor IGM 100/981; (B) Detail from cast of red box in (A), with arrows showing six evenly spaced feather quill knobs; (C) View of right ulna of a turkey vulture (Cathartes); (D) Same view of Cathartes as in (C) but with soft tissue dissected to reveal placement of the secondary feathers relative to the quill knobs; (E) Detail of Cathartes, with one quill completely removed to reveal quill knob; (F) Same view as in (E) but with quill moved to the left to show placement of quill, knob, and follicular ligament. Follicular ligament indicated with arrow. Photographs by Mick Ellison.

A recent museum exhibition of feathered dinosaurs gives one view of how they may have appeared.

A new look at some old bones have shown that velociraptor, the dinosaur made famous in the movie Jurassic Park, had feathers. A paper describing the discovery, made by palaeontologists at the American Museum of Natural History and the Field Museum of Natural History, appears in the 21 September issue of the journal Science.

Scientists have known for years that many dinosaurs had feathers. Now the presence of feathers has been documented in velociraptor, one of the most iconic of dinosaurs and a close relative of birds.

The fossil specimen that the group examined was a velociraptor forearm unearthed in Mongolia in 1998. They found on it clear indications of quill knobs — places where the quills of secondary feathers, the flight or wing feathers of modern birds, were anchored to the bone with ligaments. Quill knobs are also found in many living bird species and are most evident in birds that are strong flyers. Those that primarily soar or that have lost the ability to fly entirely, however, were shown in the study to typically lack signs of quill knobs.

‘A lack of quill knobs does not necessarily mean that a dinosaur did not have feathers,’ said Alan Turner, lead author on the study and a graduate student of palaeontology at the American Museum of Natural History and at Columbia University in New York. ‘Finding quill knobs on velociraptor, though, means that it definitely had feathers. This is something we’d long suspected, but no one had been able to prove.’

Previous signs of feathers on dinosaurs had been restricted to fossils found in a particular kind of lake sediment that favoured preservation of small-bodied animals.

The velociraptor in the current study stood about three feet tall, was about five feet long, and weighed about 30 pounds. Combined with its relatively short forelimbs compared to a modern bird, this indicated it lacked volant, or flight, abilities. The authors suggest that perhaps an ancestor of velociraptor lost the ability to fly, but retained its feathers. In velociraptor, the feathers may have been useful for display, to shield nests, for temperature control, or to help it maneuver while running.

‘The more that we learn about these animals the more we find that there is basically no difference between birds and their closely related dinosaur ancestors like velociraptor,’ said Mark Norell, a Curator in the Division of Palaeontology at the American Museum of Natural History and co-author on the study. ‘Both have wishbones, brooded their nests, possess hollow bones, and were covered in feathers. If animals like velociraptor were alive today our first impression would be that they were just very unusual looking birds.’

The research team also included Peter Makovicky from the Field Museum in Chicago. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the American Museum of Natural History.

The American Museum of Natural History is one of the world’s preeminent scientific, educational, and cultural institutions. Since its founding in 1869, the Museum has advanced its global mission to explore and interpret human cultures and the natural world through a wide-reaching program of scientific research, education, and exhibitions. The Museum accomplishes this ambitious goal through its extensive facilities and resources. The institution houses 46 permanent exhibition halls, state-of-the-art research laboratories, one of the largest natural history libraries in the Western Hemisphere, and a permanent collection of more than 30 million specimens and cultural artifacts. With a scientific staff of more than 200, the Museum supports research divisions in Anthropology, Palaeontology, Invertebrate and Vertebrate Zoology, and the Physical Sciences. The Museum shares its treasures and discoveries with approximately four million on-site visitors from around the world each year. AMNH-produced exhibitions and Space Shows can currently be seen on five continents in engagements that reach audiences of millions. Source: American Museum of Natural History.

Not a velociraptor but an illustration of another feathered dinosaur recently recreated. These new feathered discoveries are becoming more commonplace than once imagined.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Breaking News, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Evidence, Forensic Science, Fossil Finds, Homo floresiensis