Fossil Dwarf Buffalo Discovered

Posted by: Loren Coleman on October 17th, 2006

Public release date: 17-Oct-2006

New dwarf buffalo discovered by chance in the Philippines

First new fossil mammal from the Philippines in 50 years

CHICAGO–Almost 50 years ago, Michael Armas, a mining engineer from the central Philippines, discovered some fossils in a tunnel he was excavating while exploring for phosphate. Forty years later, Dr. Hamilcar Intengan, a friend of his who now lives in Chicago, recognized the importance of the bones and donated them to The Field Museum.

If not for the attention and foresight of these two individuals, science might never have documented what has turned out to be an extremely unusual species of dwarf water buffalo, now extinct.

The new species, described in the October issue of the Journal of Mammalogy, has been named Bubalus cebuensis (BOO-buh-luhs seh-boo-EN-sis) after the Philippine island of Cebu, where it was found. Its most distinctive feature is its small size. While large domestic water buffalo stand six feet at the shoulder and can weigh up to 2,000 pounds, B. cebuensis would have stood only two-and-one-half feet and weighed about 350 pounds.

B. cebuensis, which evolved from a large-sized continental ancestor to dwarf size in the oceanic Philippines, is the first well-supported example of "island dwarfing" among cattle and their relatives.

"Natural selection can produce dramatic body-size changes. On islands where there is limited food and a small population, large mammals often evolve to much smaller size," said Darin Croft, lead author of the study and a professor of anatomy at Case Western Reserve University.

Significant finding on several levels

Water buffalo are members of the cattle family and are placed in the genus Bubalus, which includes four living species. Two species, Bubalus bubalis and B. mindorensis are closely related, and the new fossil species appears to be a close relative of this pair.

B. bubalis is the well-known domestic water buffalo. B. mindorensis, popularly known as a tamaraw, is also a dwarf, although at about three feet tall at the shoulder and 500 pounds it is considerably larger than the newly discovered species. The highly endangered tamaraw lives only on the Philippine island of Mindoro. Two poorly known species of the genus Bubalus from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, known as anoas, are more distantly related.

The new species, B. cebuensis, teaches scientists a great deal about the entire buffalo genus. Its discovery on Cebu–in combination with the occurrence of the rare tamaraw on Mindoro and a report of fossil teeth potentially referable to Bubalus on Luzon–indicates that this genus might have once lived throughout the Philippines, most of which is an oceanic archipelago, never connected to any continental land mass.

"Documenting past mammal diversity in the Philippines, an area of extremely high conservation priority, is vital for understanding the evolutionary development of the modern Philippine flora and fauna and how to preserve it," said Larry Heaney, a co-author of the study and curator of mammals at The Field Museum. "The concentration of unique mammal species there is among the very highest in the world, but so is the number of threatened species."

B. cebuensis also can help scientists to better understand "island dwarfing," whereby some large mammals confined to an island shrink in response to evolutionary factors. This may occur due to a lack of predators (the animal no longer needs to be large to avoid being eaten) and/or limited food (smaller animals require less food).

The research could provide insights into debates on the evolution of small-bodied species elsewhere in the tropics such as the proposed new hominid, Homo floresiensis, found on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2003. "Whether or not Homo floresiensis ultimately is shown to be a new dwarf hominid species, discovery of this new fossil water buffalo provides additional evidence that dwarf species can evolve quickly in isolation," said John Flynn, a co-author of the study, and chairman and Frick Curator in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History. "Other fossil dwarf mammal species likely remain to be discovered in the poorly explored island systems of tropical Southeast Asia."

The discovery of B. cebuensis supports the hypothesis that the tamaraw evolved to a small size due to its island habitat. Further, the fact that B. cebuensis lived on a smaller island than the tamaraw and evolved into a smaller size than the tamaraw supports the hypothesis that the size of an island plays a role in island dwarfing: the smaller the island, the smaller the dwarf.

The new discovery also shows that dwarfing can affect different parts of the body differently. For example, B. cebuensis had relatively large teeth, which is typical of island dwarfs, but also relatively large feet, which are usually reduced in dwarfing.

Scientists were able to determine the size and features of the new species based on a partial skeleton consisting of two teeth, two vertebrae, two upper arm bones, a foot bone, and two hoof bones. The fossil could not be dated with certainty, but the authors estimate that it probably lived during the Pleistocene ("Ice Age"), probably between 10,000 and 100,000 years ago, but it is possible that it is younger.

The discovery demonstrates that there are fossils to be found in the Philippines, which rarely produces fossils due to its hot, wet conditions, which are not conducive to fossil preservation. Only a few fossils of elephants, rhinos, pig, and deer have been found previously, according to Dr. Angel Bautista, a co-author of the study and curator of anthropology at the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila. "Finding this new species is a great event in the Philippines," he said. "We have wonderful living biodiversity, but we have known very little about our extinct species from long ago. Finding this new fossil species will spur us to new efforts to document the prehistory of our island nation."

The Philippines include more than 7,000 islands. During the last glacial maximum about 20,000 years ago, much of the water in the oceans was frozen in glaciers, resulting in much lower sea levels–about 400 feet lower. Because of this, some groups of current islands within the Philippines became connected by land. Some of the mammals, including water buffalo, probably migrated to the Philippines during these periods by swimming short distances between islands. Once the glaciers melted and sea levels rose, these mammals became isolated on their respective islands. Over the years, they evolved into the unique species found there today.

According to Heaney, about 200 native mammal species currently live in the Philippines, and nearly two-thirds of them are endemic (only found there). Only Madagascar has a higher percentage of endemic mammals.

"This discovery highlights the importance of making fossils available for scientific study," Croft said. "If not for the generosity of Mr. Armas and Dr. Intengan, we probably never would have known about this extinct species."

###

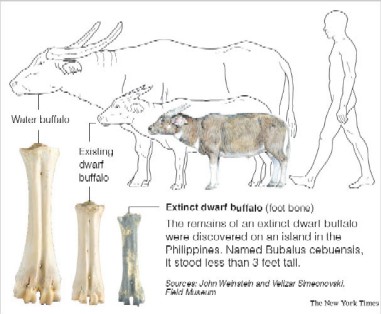

Color drawing of newly discovered species of buffalo. Click on drawing for full-size version.

The Field Museum commissioned a color reconstruction of what Bubalus cebuensis probably looked like. This drawing shows the extinct dwarf water buffalo in proportion to the tamaraw (a dwarf water buffalo that lives on the Philippine island of Mindoro); a full-sized water buffalo; and a human being. B. cebuensis, which once lived on the Philippine island of Cebu, shrunk due to "island dwarfing," whereby some larg

e mammals confined to an island shrink over time in response to evolutionary factors, such as a limited food supply and a lack of predators.

Illustration by Velizar Simeonovski, Courtesy of The Field Museum Field Museum mammalogist examines fossil

Lawrence Heaney, curator of mammals at The Field Museum and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Mammalogy, holds the fossil humerus of B. cebuensis, a newly discovered species of dwarf water buffalo, and a humerus of the domestic water buffalo. The extinct species was described based on a fossilized partial skeleton consisting of two teeth, two vertebrae, two upper arm bones, a foot bone, and two hoof bones. Photo by John Weinstein, Courtesy of The Field Museum (GN90881_32d)

Discoverer of B. cebuensis shows site where he found fossil

Michael Armas stands by the entrance to the tunnel where he found the fossilized bones of an unusual dwarf water buffalo, now extinct. He collected the bones and kept them safe for four decades until a friend suggested that they might be scientifically important. Armas donated the fossil to The Field Museum in 1995.

Photo by Lawrence Heaney, Courtesy of The Field Museum

The unlikely discoverer of B. cebuensis holds fossil

Michael Armas poses with the fossil bones he found on the Philippine island of Cebu and 40 years later donated to the Field Museum for study. Had it not been for his attention and foresight, science might never have documented what has turned out to be an extremely unusual species of dwarf water buffalo, now extinct.

Photo by Lawrence Heaney, Courtesy of The Field Museum

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Every time some scientist says “That animal could not have those features because … (fill in the blank)”, some new find turns up and proves that statement wrong.

You’d think they’d learn to never say never.

Perhaps the Species is still living on one of the Thousand Islands of the Philipines. I hope so!.

I think the thing that strikes me the most about this story is the fact that the fossil record is not complete. Which, in my opinion, tends to negate the argument that BF does not exist because there is no fossil record for them. Please correct if I am wrong, but I seem to recall that all they have for proof of Giganto is some teeth ? No fossils, no bones, just teeth.

How many other species are out there that leave only scant remains behind ?

I think giganto ate the dwarf buffalos. They were easier to catch.

skunkape_hunter,

Interesting observation. I’ve often wondered about that myself, the fact that “real” scientists will infer amazing things from a single jaw bone or tooth or ankle, but discount cryptids for a “lack of evidence”.

In defense of paleontologists, there is much that can be inferred by a trained, experienced scientist, from a single tooth or scrap of bone. Many prehistoric animals are known, at least at first, from such meager finds alone. Sometimes the initial conclusions drawn from such fossils are later proven wrong after more fossils of the same type come to light. Often the fossils are fought over for years by scientists whose viewpoints differ.

The difference in those fossil animals and cryptids is that the fossils are available and they are known to be fossils of an animal that actually existed… hard physical evidence, no matter what its interpretation by experts, for further study. The material is unquestionably (in most cases) a fossil of SOMETHING.

For most cryptids, the evidence may be there in sometimes almost overwhelming quantity, but the quality of the evidence still leaves much to be desired. There are a lot of sightings and other anecdotal accounts, but most of the physical evidence has not held up to close scrutiny, or else it is so ambiguous in nature that it cannot be used to conclusively say, “This is definite evidence that this creature exists”.

All animals, cryptids included, leave their mark on the environment, of course, and sooner or later those traces will come to light. It’s true also that evidence left by animals can go unrecognized in some cases. I beleve that there is a strong possibility that many currently cryptid species will be proven to exist beyond a shadow of a doubt.

If a creature doesn’t exist, it just doesn’t exist, and no amount of wishing will change that. But it’s a mistake to say that a creature does not exist just because the evidence for its existence is flimsy. The next spectacular find may be right around the corner.

kittenz, what you said may be true, the only problem I have is that those first guesses get taught in school as fact and then by the time that more info can be found the scientists that find it are students of the original idea (as fact) and few are willing to go against the flow, as it were. I’m just glad to see there are some who are willing to at least look, question and study what they can. Without those few, the discoveries of the last few years would not have happened. Now if we could only find the funding for some of us to do the searching here at home. This story also shows something that normally happens as well. 50 years ago the fossils are found and a friend donates them to those who make the discovery. I just wonder how many other fossils have been overlooked and just put away somewhere and forgotten.

I agree, shumway10973. There could be fossils languishing in a drawer somewhere, or sitting in someone’s bookshelf, that hold the key to our knowledge of some creature’s existence.

Almost half of the “new” finds in Paleontology in recent years have come from researchers rummaging through museum basements. Many field paleontologists, especially in previous centuries, were looking for that big, dramatic find, and so were liable to not spend much time on a scrap of what they thought was some small turtle, or deer, or whatnot. Other fossils, recieving only a cursory glance because more interesting things were present, have been mislabeled.

I beleive this is a very important find, my birth place has always been known for it’s high rate of endemism, plants and animals though it’s quite unfortunate that my ancestors have a very poor record in environment protection.