Prominent Pennsylvania Puma Seeker Dies

Posted by: Loren Coleman on February 19th, 2006

Cryptomundo Exclusive Obituary

On Saturday, February 18, 2006, at 6:05 AM, in Pennsylvania, one of the country’s best-kept-secrets, a modest but renowned behind-the-scenes eastern cougar hunter passed away. Roger Cowburn, 77, of Potter County, Pennsylvania, died.

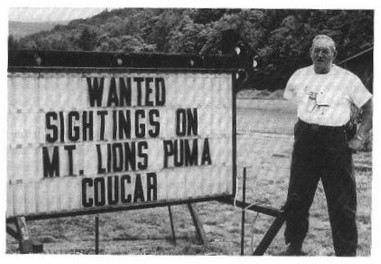

Roger Cowburn of Galeton, Pennslyvania, is a member of the Eastern Puma Research Network, a group actively searching for evidence that eastern panthers are still found in parts of eastern North America. (G. Parker)

The Penn State’s Nittany Lions are nationally known, mostly as a football team. But the “Nittany Lions” didn’t pop out of the air as a name. Nittany is the mountain where, legend has it, Pennsylvania’s last puma was shot.

But Roger Cowburn knew the last mountain lion of Pennsylvania was not really dead. Whether you call it one of its hundreds of names, a cougar, painter, panther, puma, mountain lion, Puma concolor, or Felis concolor, Cowburn had found proof that convinced him the large, long-tailed cats still lived in the state.

Cowburn understood the forests and fields, and appreciated what animals were in them. As The Valley Independent city editor and outsdoor sports reporter Bob Frye wrote a few years ago:

Roger Cowburn grew up in the woods. By 1940, at the age of 12, he was a hunter and by 1955 he was guiding “flatlanders” – what he and his neighbors around Galeton, Potter County, used to call hunters from New York and southern Pennsylvania – when they came up to hunt. Things went well enough – he was getting $10 per hunter per day – that by 1966 he bought and opened a hunting lodge that employed eight and slept 56.

Cowburn’s lodge was often filled with deer hunters who had come to Pennsylvania, and he was as good a guide as there was around for knowing where to go to find the animals. “I could take you [to special locations] at night and you could see 500 deer in one field,” he told Frye.

Cowburn was one of the first to see the deer population was exploding in Pennsylvania, beyond what the state’s game commission could do to manage the increase. The deer population was getting out of control, causing widespread crop damage and devastating the very forests they live in. Cowburn surprised many of his family and friends by being an early advocate of an open doe season.

Frye recalled:

“Guys like my dad and my uncle used to go around to sportsmen’s clubs and buy all of the doe tags and then not hunt. They wanted to make sure nobody killed the doe. They’d buy them up and burn them up,” Cowburn had remembered a few years back.

Cowburn, who succeeded his dad and uncle as president of the Ulysses Conservation Club, tried to convince them they were wrong. The overabundance of deer was killing farmers, he told them, and destroying the deer’s own habitat. He couldn’t reach them, though. “My dad used to fight me something awful over the doe.”

“That generation is gone,” he says. “They were good hunters, and good sportsmen, but they missed the boat on doe. I think at least some people today are starting to realize that, and it has to be. It has to be.”

Something else was happening with an increased deer population. The surviving mountain lions tucked away in wilderness pockets in Pennsylvania was coming back too, even though few in the Pennsylvania Game Commission believed it, or even believe it today.

Cowburn thought otherwise. For years he’d interviewed witnesses who had seen the big cats in the state. And he had collected material evidence that people had a hard time denying too. In one meeting, State Sen. Roger A. Madigan, R-Towanda, and state Game Commission officials viewed such evidence presented by retired Mansfield University professor Dennis Wydra that Wydra believed confirmed the existence of mountain lions in the wilds of central Pennsylvania. The closed-door meeting at Madigan’s Williamsport office had a bigger impact because of the physical evidence there.

Wydra displayed plaster footcasts of bear, wolf and mountain lion tracks “taken by Roger Cowburn of Ulysses,” as one media account mentioned, in almost a footnote whisper, at the Lick Run area on State Game Lands. Wydra also showed a shirt that supposedly had been found with mountain lion fecal matter and large claw marks on it. Behind-the-scenes, but important, that was the way Cowburn liked it.

One author, who will remain unnameless, perhaps not even having talked to Roger Cowburn, had quoted Cowburn as saying that the Pennsylvania Game Commission “was no more trustworthy than the KGB.” Maybe it is merely an allegorical tale told among the media and puma seekers in Pennsylvania, but even if he didn’t say it, Cowburn probably felt it. He knew the mountain lions were leaving tracks in the state, and he’d seen the proof, no matter what any official at any agency had said.

Roger Cowburn had many true friends among the three organizations gathering eastern cougar sighting information and data, and they’ll all miss him. But this isn’t about them; it’s about Cowburn and his achievements, because for a long time his was a name you didn’t hear. But he was there, in the woods, in the field, in the background, tracking, talking, and teaching about the pumas still in his state.

It doesn’t matter any longer to Roger Cowburn. He won’t be searching for them tomorrow.

Cowburn knew the big cats were still out there. That was enough for him.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

The source for the origin of “Nittany Lion” being due to the last puma killed on the mountain named Nittany (at the end of Nittany Valley) is the Philadephia Inquirer, January 24, 2006. This was repeated in other news dispatches due to three new mountain lion cubs from South Dakota being placed at the Philadelphia Zoo.

Perhaps the media was creating a new urban myth, or that’s what someone at PSU wanted to see in print, but that’s the “Nittany Lion” story given there.

Other websites have other stories, of course.

The Inquirer seems to be full of crap on this. “Nittany” was around before Penn State, but it’s certainly been used by the school (and half of the local businesses within 20 miles) for years. If anything today, Nittany is least a powerful brand for Penn State.

Here’s a little bit on the popular local legend on the etymology of the word.

PSU offers this quick study on Nittany.

As a side note (or back to the real point, anyway), Pennsylvania has a real, two-fold, deer problem. The first part is that there are too many deer. The second part is that many (but certainly not all) hunters refuse to recognize this problem. Gary Alt, the former Game Commission director, was basically driven out because he wanted to decrease the state’s deer herd. Hopefully hunters will come to their senses, because there are a lot of dead deer on the side of the road in Pa.

Thanks for this article. I have found four great sites for those interested in the Eastern Cougar or my favorites: the panther or catamount.

Here’s the sites:

The Panther Project

The cougar

Eastern Puma Research

Cougar Network

Claims have been made that the last lion was killed on Penns Creek Mt. in Snyder County, PA. I feel that it was premature for the Game Commission to declare the lion population extinct in PA. Such a secrative animal could easily survive undetected, especially in the northern regions of the state. Livestock predation would not be an issue. Freshyill is quite right, PA is loaded with deer. You have to understand that many in Pennsylvania regard the PA Game Commission as a joke. Several years ago, rumours were running that the Game Commission were importing Mountain Lion into the state to control deer population. They denied this but there have been a lot of sightings since then.

I complained about this for two reasons. One, you do not release a dangerous animal into state parks without warning the public. Two, western lions will contaminate the gene pool of eastern lions. Your chances of finding an Eastern Cougar and proving it to be a separate species genetically decrease every year.

Thank you Loren for such an excellent obit on Roger. He would have been very proud of this article.

Roger was one of the best of the best. He will be greatly missed, especially by us (Eastern Puma Research Network), as he was PA Chief Field Researcher.

He gave us data on where a cougar may have been killed. This weekend, special search parties are seeking it.

Loren:

Thank you for such a fitting tribute to our close friend Roger Cowburn who’s search for wild cougar evidence in northern Penns Woods lasted from the 1960s thru late 2005. He was one of the last true dedicated researchers and a excellant tracker who found the necessary data to prove cougars & black panthers continue to survive in northern Pennsylvania.