Great Auk

Posted by: Loren Coleman on February 2nd, 2007

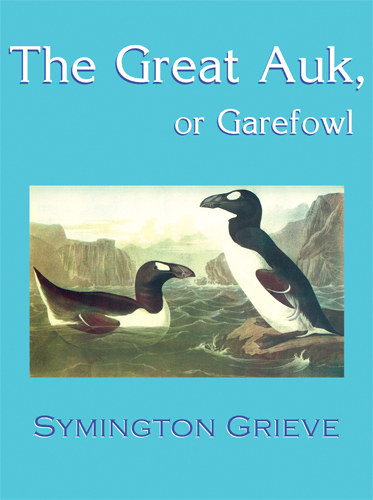

Chad Arment’s Coachwhip Publications has announced the release of The Great Auk, or Garefowl. Below is Arment’s overview of the contents.

Grieve’s classic text on the Great Auk provides a wealth of information on early knowledge of this extinct bird: records of specimens (birds and eggs), lists of former breeding-grounds, and stories from sailors and explorers who had first-hand sightings of the auks before they disappeared. Discussion ranges from archaeology to etymology: where the garefowl got its name. (And, are they the true “penguins”?) First published in 1885, this scarce reprint brings back to light the detailed scholarship of one who could only look to the past as his era’s scientific community realized the passing of a fascinating creature.

This is a non-facsimile reprint. It includes a black-and-white printing, over several pages, of the original large color fold-out map of the great auk’s known range.

The Great Auk, or Garefowl

Symington Grieve

ISBN 1-930585-35-7

Retail $14.95 (USD)

192 pp. / Paperback (8.25 x 11)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

For illustrative purposes, below please find some images of paintings of the Great Auk. (Please note: not known to be found in The Great Auk, or Garefowl).

The Great Auk, painting by Johannes Gerardus Keulemans, via Wikipedia.

The Great Auk, painting by J. G. Wood, via Wikipedia.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Truly a fascinating species and a tragic tale of its demise. Is it absolultey impossible that none could still survive somewhere? I hope that science will clone this animal someday!

Another example of man’s greed evidently causing a species’ demise. Not unlike the dodo, or some species of the Galapagos tortoise, or even the passenger pigeon. There was little real need for the great auk to have been slaughtered to extinction, and what a tragedy it’s most likely gone for all time.

It was my understanding that the Great Auk was the first bird to which the name ‘Penguin’ was attached. Or at least that is what has been put in books.

Ceroill, I think you’re right on that. Supposedly from the old Welsh words for white and head.

Looks like a good read on a fascinating subject. For those interested in a surprisingly informative book on the history of the auks and many other previously extant species encountered in the old world’s expansion into the new world, I highly recommend Farley Mowat’s “Sea of Slaughter”. It provides great insight into the undiminished wildlife the fist europeans discovered when they took to boats and crossed the seas to where technology had not previously been much seen. It created incredible wealth at an inconceivable price.

For more on extinct species (Including many of cryptozoological interest), I would suggest “A Gap In Nature” by Flannery & Schouten. Just don’t expect to come away from reading the book feeling very cheery about the human race (Although, in all fairness, one particular species was entirely wiped out by a single housecat).

It is worth noting that collectors, those who clearly recognized that the Great Auk was dying out, helped hasten their collective demise in their pursuit of specimens. The last 2 Great Auks ever seen were clubbed to death by sailors hired by a collector. After their slaughter, they discovered a single egg, which had been inadvertently trampled upon in the fracas.

If I recall correctly, there may have been a few unsubstantiated reports of post-1844 sightings, but even they stopped after just a few decades, and nothing more has ever been seen of them. Despite the scarceness of people in the region of the North Atlantic, the breeding site requirements of the Great Auk were well-known, post-1844 expeditions were carried out to find them, and it is hard to imagine that they could still exist unseen somewhere. We’re not talking about a giant ape dwarfed by the forest of trees around him hiding away in caves and underbrush somewhere, but a black and white, man-sized bird breeding on flat, featureless stretches of rocky coast. I would love for one to be found, but face it, they are almost certainly no more.

I agree, that is an excellent book!

I saw either a Great Auk or razorbill one evening just in a national wildlife refuge just south of Sandbridge beach, Virginia in the spring of 1977. It was a clear full moon evening. I was startled by a large heavy bird nesting in a shallow circular nest in the sand approximately 10 yards from the high tide mark. It jumped up at me spreading its short wings. and hopped to the water using both its wings and feet to hop. Each hop covered about 6 to 10 feet. When it reached the water, it started using its wings to swim, dove under the breakers, came up and dove again. The bill was right for either of the two birds but the plumage did not have much black at all. I went back every night for a week without another sighting. At the time, I thought it was the weidest looking pelican I had ever seen.

Not that I doubt your encounter, Dburke, but based on the information you provided, I would doubt that it was a Great Auk. They were never the most agile of birds on land, at best waddling rather than leaping about as you say your mystery bird did, and they nested in rocky areas, not sand, but then, the same is true for Razorbills. Anyone else have a guess?