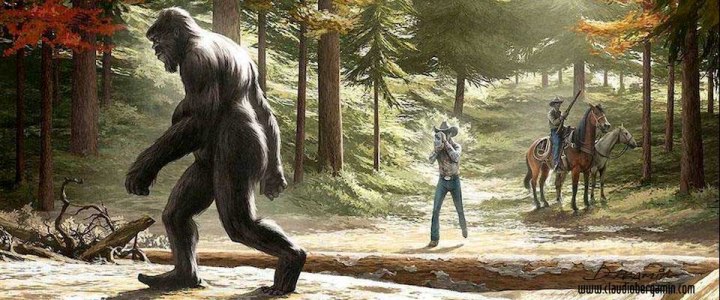

Illustration by Claudio Bergamin

July 3, 2018

Illustration by Claudio Bergamin

By Krissy Eliot

California Magazine

Last week, we published a two-part profile on UC Berkeley grad and anthropologist Grover Krantz, known to many as the original “Bigfoot scientist.” (You can find the first part of the profile here and the second half here.) Today, we examine the question of whether mythological creatures like Bigfoot are worthy of scientific analysis. The answers we discovered might surprise you.

It’s difficult to get respect when you work in a field that is referred to as pseudoscience.

Cryptozoology, the study of animals as yet undiscovered, relies heavily on folklore, citizen accounts, and amateur data collection to “prove” that legendary creatures like Bigfoot and Yeti actually exist. In the absence of empirical evidence—and of the skepticism intrinsic to scientific inquiry—such methods can be troubling if not irritating to mainstream scientists.

However, there appears to be some agreement among academics that creatures of folklore deserve scientific investigation. Why? Because cryptid studies have long led to discoveries.

“Through the history of time, there have been things that were once perceived outside of nature that were then brought into it and understood to be a part of nature,” said Cal grad and folklore professor Lynne McNeill, in an interview with Radio West. “I think that a lot of this interest in the science, or pseudoscience, of [creatures like] Bigfoot—is in crossing that bridge, bringing something unknown into the known.”

Take, for example, the giant squid.

Since Greek and Roman times (and probably before) people have been telling tales of a terrifying, tentacled sea monster of titanic size that could swamp small ships and sailboats, scaring sailors while providing fiction writers with a plethora of material. The giant squid was considered nothing but a fiction by the scientific community for centuries until 1857, when Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup managed to find a squid beak so enormous that it could only belong to a cephalopod of jumbo proportions. “From all evidences,” Steenstrup concluded, “the stranded animal must thus belong not only to the large but to the really gigantic cephalopods, whose existence has on the whole been doubted.”

Following this, bits and pieces of the giant squid were found by others—a batch of tentacles here, a head there, but no complete body. It wasn’t until the 1960s that marine biologist Frederick Aldrich would harness the power of folklore to transform myth into reality, dragging to science’s doorstep the first fully intact body of the KRAKEN.

Using the folktales from Memorial University of Newfoundland’s archives, Aldrich collected sailors’ descriptions of where and when they saw the creature, then predicted when the next sightings would occur. He put up WANTED, DEAD OR ALIVE posters featuring old black-and-white drawings of a giant squid flailing its monstrous tentacles, with the University of Newfoundland’s name at the top. “It’s a miracle he didn’t get fired,” McNeill said. Two weeks later, a sailor caught a giant squid, called Aldrich up and said, “Oh, hey. Here it is!”

“The people saying, ‘Here it is!’ are of course poor fisherman living on the coast of Newfoundland, who all along are the ones who were finding these pieces and body parts, saying the giant squid was real, and being totally discredited because they weren’t university professors,” McNeill said. “Of course, this is the sad story of people not being taken seriously until a university professor takes them seriously. But, better that than never, right?”

And the giant squid is not the only case.

The gorilla was thought to be fake until the 19th century, when naturalist and physician Thomas Savage happened upon gorilla bones in Liberia, finally proving that the species was real. It then took another 10 years for explorer Paul du Chaillu to actually see a gorilla, hunt it down, and send back the specimen. The platypus, okapi, Komodo dragon, manatee, plesiosaur, pelican, and the King of Saxony bird of paradise, among others, were only “officially declared real” by scientists after the 1700s, which means for the 18 centuries before that, they were considered to be mythical or hoaxes.

From these cases we can surmise that mysterious animals don’t reveal themselves only to scientists; they can in fact be pretty apathetic about what audience bears witness to their debut. And it is certainly consistent with scientific inquiry to believe that just because a creature is not known now doesn’t mean it never will be. Cryptozoologists often use this reasoning to justify paying heed to civilian accounts of Bigfoot sightings—an idea that even the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees, Jane Goodall, would seem to get behind.

“Does Sasquatch exist? There are countless people—especially indigenous people—in different parts of America who claim to have seen such a creature,” writes Goodall in her endorsement of Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science, a book by Idaho State University professor and anthropologist Jeffrey Meldrum. “And in many parts of the world I meet those who, in a matter-of-fact way, tell me of their encounters with large, bipedal, tail-less hominids. I think I have read every article and every book about these creatures, and while most scientists are not satisfied with existing evidence, I have an open mind.”

If the search for Sasquatch doesn’t result in finding a literal Bigfoot, studying cryptids has been shown to lead to discoveries of previously unidentified species. And recently, too.

In 2013, a documentary film company enlisted the help of Charlotte Lindqvist, a geneticist at the University at Buffalo in New York, to help determine whether the bone and fur samples they collected in the Himalayas were that of Bigfoot or Yeti. Though Lindqvist found that the samples were not from cryptids but were actually from multiple known species of bears, the samples allowed for scientific breakthrough of another kind: Lindqvist and her colleagues were able to, for the first time in history, fully sequence the mitochondrial genomes of a Himalayan brown bear and black bear. Not only that, but they were also able to deduce that over 650,000 years ago, glaciers forced a single population of bears apart, creating two isolated populations that, over time, became two distinct subspecies—the Himalayan brown bears and Tibetan brown bears that exist today.

In the same year, scientists from Oxford University and zoological museums in France and Germany put out a call asking people to send them evidence of “anomalous primates” like Sasquatch. When it was all said and done, they had 57 hair and fur samples, and almost all of them were from previously discovered mammals like black bears, dogs, cows, porcupines, and horses. However, two different samples from Bhutan and India matched a 40,000-year-old fossil of a polar bear found in Norway, though neither sample matched genetic markers in modern polar bears. Meaning that the search for cryptids led scientists to discover a species of bear that was previously unknown to science—a species that may have been in existence even before polar and brown bears diverged into different species.

So if history shows that science can potentially benefit from examining cryptozoological findings, why is that so many scientists are still adamantly against the practice? Berkeley graduate Grover Krantz, the first scientist to publicly dedicate his life and career to the search for Bigfoot (and whom we profile here and here) thought the problem for many of his colleagues is their hurt pride—they can’t bear the idea of having to admit a colossal creature like Sasquatch was right under their noses all this time.

“There’s a lot of pigheadedness about scientists,” Krantz told the Virginia Chronicle in a 1982 article about Bigfoot. “If science has missed an animal this big, science would look a little funny. So better not look for it.”

Another reason scientists don’t go public with their belief, Krantz said, is fear of being ostracized—something he knew about quite well. While working as a professor at Washington State, he was constantly turned down for grants and promotions and was almost fired multiple times for investigating and speaking openly about Sasquatch.

Krantz estimated that 10-20 percent of scientists actually do believe in Sasquatch, according to a 1978 story in the Desert Sun, but they’re afraid to come out as believers and risk their careers.

If you enjoyed this piece, check back in tomorrow, when we investigate why and how people come to believe in legendary animals like Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster. The reasons for their beliefs, Berkeley experts say, might even be rational.

Read the rest of the article here.

About Craig Woolheater

Co-founder of Cryptomundo in 2005.

I have appeared in or contributed to the following TV programs, documentaries and films:

OLN's Mysterious Encounters: "Caddo Critter", Southern Fried Bigfoot, Travel Channel's Weird Travels: "Bigfoot", History Channel's MonsterQuest: "Swamp Stalker", The Wild Man of the Navidad, Destination America's Monsters and Mysteries in America: Texas Terror - Lake Worth Monster, Animal Planet's Finding Bigfoot: Return to Boggy Creek and Beast of the Bayou.

Filed under Bigfoot, Bigfoot Report, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Evidence, Eyewitness Accounts, Sasquatch