Pleistocene Extinction Expert Dies

Posted by: Loren Coleman on October 4th, 2010

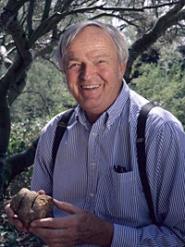

Paul S. Martin

The man who challenged paleoanthropology with a radical theory for the cause of the Pleistocene extinctions of megafauna has died. Belated word of this passing has reached Cryptomundo, and this news is worthy of our attention. Paul S. Martin took an active interest in the overlap between cryptozoology and megafauna.

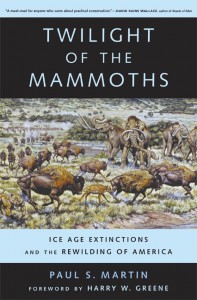

Martin was well aware of cryptozoology. In his 2007 book, Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America, Paul S. Martin discussed the topics that mutually interest you, me, and him. On pages 98-99 of that tome, Martin penned a subsection entitled “Cryptozoology, Ground Sloths, and Mapinguari National Park,” in which he addressed the interest of cryptozoologists (he calls us “cryptos”) in Pleistocene megafauna.

Photo of Paul S. Martin by Ceal Smith.

Martin especially looked at the well-funded serious search conducted by Harvard-trained ornithologist David Oren for the mapinguari in the Amazon rainforest. Martin mentioned that Oren was repeating the pursuit of living ground sloths that took place a century earlier in Tierra del Feugo. Martin also noted that ground sloths survived into the Holocene in the West Indies (a fact little noted by cryptozoologists, even).

David Oren was using a Bullyland Megatherium, shown below, when gathering ethnoknown material. (The kind of replica that Oren employed has been discontinued, but it can sometimes be found at online auctions. This model is on display at the International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland, Maine.)

The special appeal of the Bullyland Megatherium, at 6.25″ tall, is its upright stance and a generally active appearance. The locals in Brazil responded positively to David Oren’s use of this replica during his Amazon rainforest interviews.

Martin also noted his conversations with his “astute cryptozoological friend” the late Richard Greenwell (they were both at the University of Arizona). Greenwell reminded Martin of the discoveries of the coelacanth and recent large new quadruped ungulates found in Vietnam-Laos.

While Martin felt there was little chance of finding the ground sloth alive today, he did write that “Would I love to be proved wrong? Yes, indeed! One side of me is whole heartedly rooting for David Oren. What a thrill it would be for me to see a living, breathing ground sloth in the flesh. More than that, their discovery in the Amazon would fuel the initiative needed to set aside one or more large reserves of the world’s largest rain forest. The ongoing global destruction of rain forest is one of the unspeakable tragedies of our time.”

Here is an adaption of his university’s press release on his death:

Paul S. Martin, 82, the University of Arizona geoscientist who developed the idea that overhunting drove North America’s large Ice Age mammals extinct, died September 13, 2010, at his home in Tucson, Arizona.

“More than 40 years ago, Paul framed a scientific question: What was the role of humans in Pleistocene extinctions? It’s the greatest “whodunit” in science,” said Karl W. Flessa, a UA paleontologist and a long-time colleague of Martin’s.

Martin insisted that early humans had hunted North America’s Ice Age big game, including ground sloths, camels, mammoths and mastodons, to extinction.

“The issue has engaged generations of scientists, students and the general public ever since,” said Flessa, professor and head of the UA department of geosciences. “Paul warmly welcomed both supporters and dissenters. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. It wasn’t just a matter of disarming his opponents with kindness. Paul really wanted to see things the way his opponents saw them, in order to understand even more about his favorite topic–Pleistocene extinctions.”

Vance Haynes, a UA professor emeritus of anthropology and geosciences, reiterated Martin’s desire to learn from people with different viewpoints and his thirst for knowledge: “Unlike so many people who get infatuated with their own theories, he spent his professional career inviting criticism. He put together two critical conferences about Pleistocene extinctions, and the volumes that came out of those were pace-setting.”

Martin’s wide-ranging interests made him an interdisciplinary researcher before interdisciplinary was a buzzword. Martin’s work bridged ecology, anthropology, geosciences and paleontology in a way that had not been done before.

A native of Allentown, Pennsylvania, Martin earned a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Cornell University in 1951. He earned his master’s degree and doctorate in zoology from the University of Michigan in 1953 and 1956, respectively. He was a postdoctoral researcher in biogeography at Yale University from 1955-56 and at the University of Montreal from 1956-57. He joined the UA as a research associate in the Geochronology Laboratories in 1957. He became an assistant professor in 1961 and rose through the ranks, becoming a professor of geosciences in 1968. He retired from the University as an emeritus professor of geosciences in 1989.

In addition to his studies of Pleistocene extinctions, Martin is also known worldwide for his and his students’ research on the long-term ecological and climatic records contained in packrat middens. He and his students also studied paleoecology and paleoclimate using other natural records, including pollen, tree rings and the vegetation preserved in fossilized ground sloth dung. The center of those studies was the UA’s The Desert Laboratory, three buildings perched atop Tumamoc Hill, then just outside of Tucson and surrounded by desert.

The interdisciplinary nature of Martin’s own research fueled a spirit of collaboration and creativity in the students from zoology, botany, geology and anthropology who gathered and conducted research on “The Hill,” as people called it.

Former graduate student David W. Steadman said, “There were graduate students with highly varied backgrounds who did lots of fieldwork together and ate lunch together. … All of us up there truly appreciated what we had. Nobody had to tell us that we had something special going.”

The importance of going into the field to study the natural world was a crucial component of Martin’s approach to research. His wife, Mary Kay O’Rourke, said, “A thing that is most remarkable about Paul’s life is his vast array of field experience. … He was all about the field work.”

Martin’s field trips were legendary because he inspired people to explore, enjoy and study the natural world. Steadman said, “I look back on those days with euphoria. He knew the best places to go, the neatest regions to explore. … He made everybody, no matter what your background or your educational level or expertise, feel welcome and that they could contribute.”

Martin’s interest in the natural world started in childhood and was encouraged by his parents, Steadman said. Martin attended Cornell University to study zoology and fell in love with Mexico while on a bird-collecting field trip.

The trip began Martin’s life-long interest in Mexico and in how tropical flora and fauna came to be. “He was smitten by the lifestyle of rural Mexicans and by the Mexican countryside,” said Steadman, now associate director for collections and research at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainesville. “There was something about Paul that put him in a really special good mood once he was south of the border.”

Martin’s devotion to field work and love of remote places was particularly notable because he had contracted polio in the early 1950s and often needed a cane or crutches to get around.

Once Martin and his wife visited Steadman at a remote field camp in the Galapagos accessible only by boat. Camp was a two-mile hike over lava and up a cliff.

“I questioned whether Paul could make it,” Steadman said. “He said, ‘I’m going to make it, don’t wait for me.’ … After I don’t know how many hours, here shows up Paul. Bloody – there wasn’t a place that wasn’t cut. Bloody, sweaty and grinning from ear-to-ear.”

Haynes said, “He was a remarkable person, and I thank my lucky stars that I was associated with him. He’s going to leave a big hole in the profession.”

Martin is survived by his wife, Mary Kay O’Rourke, an associate professor of public health at the UA; his sons Andrew, Neil and Thomas; two nieces and four nephews; and two granddaughters.

From a press release authored by Mari N. Jensen of the College of Science, University of Arizona.

For another remembrance of Dr. Martin, see here.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Sad news. I always enjoyed reading his perspectives which brought the distant past into context. Whether his theories are proved to be accurate or whether some other process took place to drive that tragic extinction event, the importance of thinking in the long term was made poignant by Dr Martin’s work and his legacy has resulted in a more comprehensive understanding of the world around us now.

Read the current issue of National Geographic, in which Martin’s name and work are prominently featured in an article on Australian megafaunal extinctions.

RIP.