July 30, 2008

You remember the scene from the end of the first Indiana Jones movie? Recall the endless rows of boxes in storage in that secret warehouse?

Of course, the reality is that most large museums around the world actually do have such storage areas.

The “outfront” exhibits at most museums are impressive. But, for example, I was reminded quickly in Alberta, once again, that less than 10% of the holdings of a museum are what the public sees.

The Columbian mammoth is on exhibit in Alberta with other Pleistocene mammals.

When I visited the Royal Alberta Museum, the director of Communications, Marketing & Education Chris Robinson and museum director Bruce McGillivray gave me a behind-the-scenes tour of the mysterious Room N008.

One of the first things that hits you when you come into this oversized, bright, clean room is the shelves upon shelves of specimens – fossils, skulls, mounted heads, and taxidermy mounts. There’s enough in there for a few museums. But that’s the point, right?

Part of the mission of any museum is study and research. So, for example, while the rows of bison skulls – fossil and contemporary – hardly would make for a good exhibit, they have a storehouse of information for researchers, especially those interested in Pleistocene bison and current wood bison.

I also noticed, immediately, besides regional specimens one might find in Alberta, the museum housed a lot of exotic mounts. I asked Chris Robinson to fill me in.

He informed me that the bulk of the natural history specimens in N008 were donated to the province by Eric Lafferty Harvie (1892-1975), a prominent Alberta oilman and lawyer. The 63,000 item-strong collection is named the Riveredge Foundation Collection.

Eric Harvie formed the Glenbow Foundation in 1955. Spurred by a strong interest in collecting material relating to the history of western Canada, Harvie collected books, art, documents, records, manuscripts, and objects that traced the material history of early settlers and Aboriginal peoples in Alberta.

Harvie’s collection, however, expanded beyond Alberta’s borders to include the art and culture of the world. In 1966 his collection became the Glenbow-Alberta Institute. The Government of Alberta built the Glenbow Museum in 1976. Eventually, with the evolution of the institutions, through the provincial museum to the royal museum, the collection ended up in N008.

It was clear from what I could see in my overview that the holdings were incredible.

Walls were covered with trophy heads and taxidermy items were on several rows of shelves.

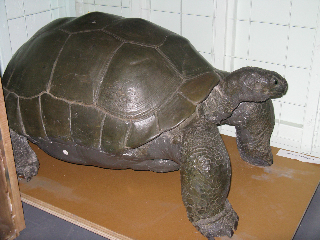

Over in the corner, one might find a huge Galapagos tortoise.

Turn around, look under a sheet of plastic, and there’s a baby musk ox.

Meanwhile, back in the general public spaces, I saw what happened to some of the Room N008 residents.

A few back area specimens find their way, now and then, upfront. For instance, the majestic wood bison, above, is unassumingly presented in a public corner. This wood bison is notable as it is on display, uncelebrated for the great mammal it is, being re-discovered only in 1959. It is before a wall that was to have a habitat painting on it but the money ran out. You will note that a cowbird is on its back; a detail I found to be very cool. (Plans are afoot to bring the wood bison more into the fore, in the future renewal of the museum.)

Back in N008, there appears to be the hint of hidden treasures. Dr. Jim Butler told me that only recently, when a giant ground sloth specialist visited the museum he found three fossil bones of the ground sloth kicking around in a collection of uncatalogued Alberta fossil bones.

The room contains many items that have been brought up from local Pleistocene digs.

What’s this skull? (Answer at the bottom.)

Over in the corner, director McGillivray pointed out an old mount, which he jokingly said might be seen by some as an unknown cryptid, because the taxidermy showed such a scary presentation. He extracted it from the wall, and we used it as an example of what we could find out about any one object.

It certainly looked frightening, although, of course, we all knew it was hardly a “great mystery canid.” Still, we probed further into its background.

Chris Robinson recorded the exact notes on “the mounted fox head,” which was sitting next to the Galapagos tortoise. It had the following notation on it:

ACC#450 – FOX

R100 603

Atherstone

Swain’s Park

Wednesday, November 13, 1895.

Chris Robinson then forwarded this to me: “I’ll see if our collection manager can dig up anything further. I think the fox perhaps looks stranger that he should, given the peeling paint in the mouth and the chipped teeth, and 113 years on a board in a basement likely didn’t help his complexion any either.”

Robinson soon emailed back with this:

“It was part of the Riveredge Foundation accession that was acquired in 1979. Most of these types of old European trophy mounts originated from the Duke of Bedford collection, which Harvie likely acquired through auction. Atherstone is the town and Swain’s Park is probably the named wood near there.”

I researched this further, and did find there is a tradition called the “Atherstone Hunt,” even with its own special “button,” (shown below).

I learned that the Atherstone fox hunt extends 24 miles north to south and 18 miles east to west, covering parts of Leicestershire and Warwickshire and small areas of Staffordshire and Derbyshire.

The hunt dates from 1804, during the Mastership of Squire Osbaldeston (1815-1817) the present country of the Atherstone was defined. Between 1930 and 1950 the hunt was divided.

The Master and hunt staff wear distinctive red jackets with white collars and blue collars for lady members, the evening dress jacket is red with gorge de pigeon (grey facings).

So, while some mysteries may exist in various museum storage rooms like N008 around the globe, a lot of the bizarre looking mounts in the back room could merely hide some mundane human activity, like a fox hunt.

Meanwhile, I’m not done with the Royal Alberta Museum. There’s some separate bird stories I learned there that I want to share at another time. After all, museum director Bruce McGillivray is, first and foremost, an internationally-recognized birder (he authored the following book) and more tales are to be told.

++++

Answer to the mystery skull: Darren Naish says, “It’s definitely a mylodontid sloth, and it looks like it could be Paramylodon (specimens of which are often labelled as Glossotherium).”

Wikipedia has this to add about the ground sloths: “Cryptozoologists often identify the mapinguari, a mythical forest creature of the upper Amazon basin, with a surviving tropical ground sloth or folk memory of these animals.” 🙂

Harlan’s Ground Sloth (Paramylodon harlani), a mylodontid, skeleton shown.

Paramylodon reconstruction.

Meanwhile, don’t forget the International Cryptozoology Museum….

Please join these over 150 people, and support the museum today. Know you may directly send a check, money order, or, if outside the USA, an international postal money order made out to

International Cryptozoology Museum

c/o Loren Coleman

PO Box 360

Portland, ME 04112

Or use PayPal to lcoleman@maine.rr.com

Since July 3th, donations are coming in at only less than $100 a week. There is some way to go to reach the goal of $15,000 by September 1st.

Please “Save The Museum”!

Easy-to-use donation buttons are now available here or merely by clicking the blank button below (which you can use without being a member of PayPal).

Thank you, everyone!

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Artifacts, Breaking News, Classic Animals of Discovery, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Fossil Finds, Megafauna, Men in Cryptozoology, Museums, Photos