May 17, 2014

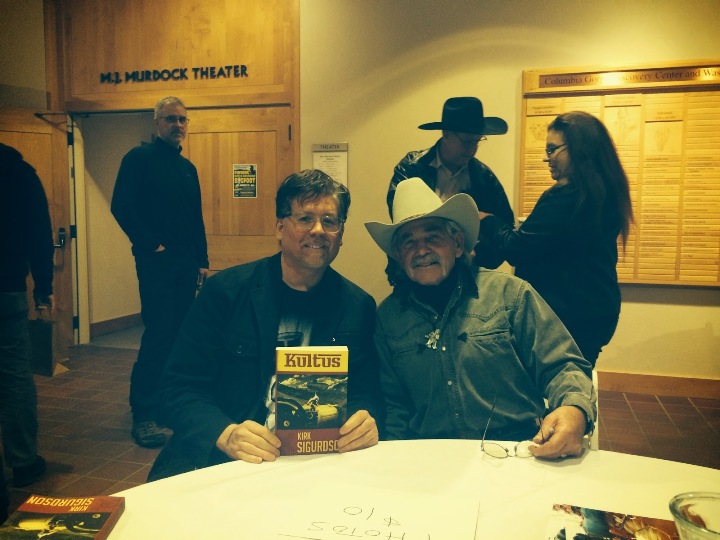

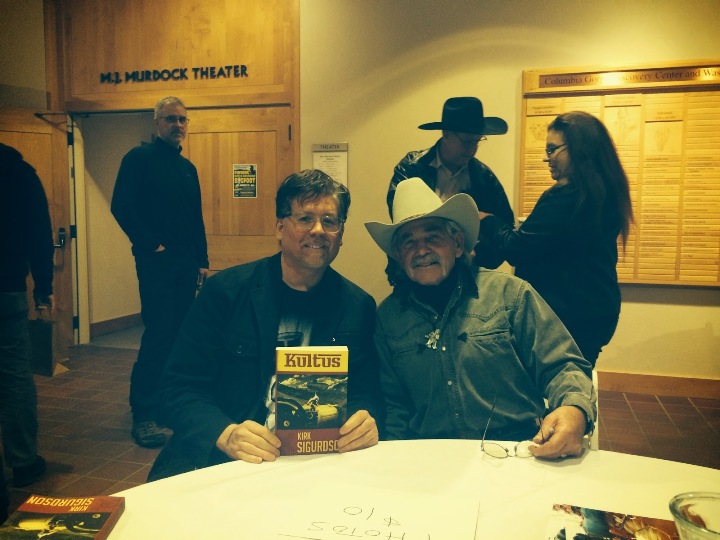

Bob Gimlin is wise, as well as kind. Every time I hang out with the dude, I appreciate him even more. Here I am (above) at the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center with Bob in early 2014, where he gave a brilliant account of his experience with Roger Patterson at the time the famous bigfoot footage of “Patty” was taken.

I’ve had the chance to chat one-on-one at length with Bob at parties and backyard BBQ’s several times. He is quite the conversationalist, and his refreshingly down-to-earth “cowboy perspective” is much appreciated. I, myself, worked on a cattle ranch in Wyoming as a teenager. I also grew up with horses out in the country near Independence, Oregon.

Horses were a joy to ride (and a chore to clean up after) when I was a kid. My weekly duties from 4-12 years of age included caring for my own pony–a Shetland named “Misty,” that had enough of a temper to make her a challenge to ride. Still, despite her difficult temperament, which included biting and kicking (she nearly broke my leg once), I loved her all the same. Eventually, my parents, exasperated with Misty’s foul temperament, sold her to a breeder.

Up until my teens, I’d kept Misty’s saddle in apple pie condition, combing her diligently, feeding her, and making sure she was comfortable. After Misty was gone, I found that I had a lot more free time. I soon took up percussion as a hobby, as well as reading voluminously. A few years later, I began working in a nearby wine vineyard to save up enough money to buy my first drum set.

Bob laughed pretty hard when I told him about Misty, and he had some good advice to offer if I ever got it in my head to buy another Shetland. He absolutely loves horses (and ponies). They’re in his blood and he brings them up every time I see him. Bob is quite naturally in touch with the land.

There’s nothing more natural than riding a horse through the remote wilderness. For me, it’s even better than backpacking because the heavy pack always seems to provide a distraction. Up atop a horse, free of the burden of a heavy pack, you can really get a feel for the land for days on end of travel, without the exhaustion of backpacking. Bob has quite a repertoire of stories about horses and camping.

He, of course, was covering Roger Patterson (from horseback) with his rifle in October of 1967 when the famous Patterson-Gimlin film footage was taken. This footage is still the best ever taken of a sasquatch, and most people have only seen third and fourth generation (somewhat blurry) copies of the original (surprisingly clear and focused) film.

One thing’s for sure: Patty is no “blob-squatch.” Her image has become a cultural icon. Frame 352 (above) is instantly recognizable to young and old alike, from New York to Tokyo to Bejing. It’s interesting to note that this frame records the image of a nervous Patty who had turned to regard Bob Gimlin on his horse.

At the time, the sights on Bob’s rifle was pointed at Patty’s head, and his finger was on the trigger. Very few actually know this fact, but people seem to instinctively recognize Patty’s humanity. The picture shows a sasquatch literally confronting the threat of humanity; her concerned expression symbolically registers the danger our species poses to the well-being of the planet as a whole. In this way, the Patterson-Gimlin footage is more than simply iconic: it’s downright profound. At the time the footage was taken, a 750-pound Patty ambles off into the woods with her famous long-armed gait, and the telling “no-neck” turn of the head.

Believe it or not, I’m no stranger to spending time around sasquatches. I know the smell of them, the calls and sounds they utter, the way they break branches to mean different things. I know the difference between a squatch footprint (or a knuckle print) and that of a bear or an elk. In short, I’ve dedicated a tremendous amount of time and energy to familiarize myself with their calling cards, as well as their behavior.

Be this as it may, I’ve only had one distinctive sighing after one hundred-odd trips to hot spots (remote locales where sasquatch activity is high, often with a history of contact that predates European settlers) over the past twenty years. When the sighting took place, a friend stood at my side. His loaded rifle was resting on the front seat of my Jeep.

After the tension of living through that dramatic sighting, I certainly recognize the importance of Bob covering Roger, who was risking a great deal running across the rocky stream with a Kodak K-100 camera pressed up tight against his face. Both men were quite brave that day, as well as being intrepid enough to ride up into some very remote and rugged forestland at a time when very few people knew that sasquatches even existed, much less had the foresight to go looking for them.

Precise location of my bigfoot sighting, near Spirit Mountain, Oregon

Having a big bore Marlin nearby, during a “Class A” bigfoot sighting in the early autumn of 2008, certainly helped me to enjoy the experience, which lasted about twenty minutes in a stare-down match. The huge sasquatch was perched atop a rock quarry near Spirit Mountain, which is located on an Indian reservation.

Needless to say, the fella was none too pleased about a recent clear cut that could not have been more than a week old. The freshly cut Douglas fir and hemlock trees were still fragrant enough to smell. He announced his presence with a deep moan. In fact, if he hadn’t done that, my friend and I would never have seen him.

Read the rest of the article on my website here.

Kultus is now available at Amazon.com.

About Kirk Sigurdson

Kirk Edward Sigurdson attended New York University, where he earned a Master's degree in English literature. His master's thesis entitled "A Gothic Approach to HP Lovecraft's Sense of Outsideness" was published in Lovecraft Studies Journal.

After writing three novels while living in Manhattan's East Village, Sigurdson returned to his native state of Oregon. It wasn’t long before he began work on a fresh new novel that drew upon his knowledge of the sasquatch phenomenon.

As research, he ventured dozens of times into sasquatch "hot spots" for overnighters, often with friends who shared some very unique experiences. He also drew upon childhood exposure to sasquatch calls and knocking that occurred during family camping trips to Horseshoe Lake in the Cascades mountains.

Kirk Sigurdson is currently a Professor of Writing and English literature at Portland Community College.

Filed under Bigfoot, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Kultus, Men in Cryptozoology, Sasquatch