A Passion For Field Guides: Updated

Posted by: Loren Coleman on February 23rd, 2008

Look, to be honest, I love field guides.

I don’t merely have a shelf of field guides. I literally have a bookcase full of them, over a hundred different titles. With more in storage. I have such a passion for them, I wrote a couple and am planning on more.

But what do we do with all of them?

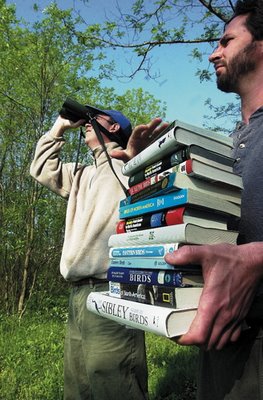

I recently saw this amusing photo on a bird books digest forum, with that birdwatcher out in the field with an armful of field guides. It is a paradox, indeed. You want to take field guides with you into the bush, but they can’t become a barrier to your pursuit of the wildlife.

Have you every heard of the University of Illinois’ unique online location, the International Field Guides, which is a searchable website?

The site merges the book A Guide to Field Guides: Identifying the Natural History of North America by Diane Schmidt, Biology Librarian at the University of Illinois, and its companion Web site International Field Guides. After the publisher returned copyright to the book to Diane Schmidt, she decided to combine the two products and create a searchable database of field guides for plants, animals, and other objects in North America and around the world. Except where noted on her site, all guides listed there were personally examined by Ms. Schmidt.

In general, in the larger world of field guides, you have to make choices. So let’s take a quick journey of various published field guides.

Field guides can be very specific or extremely generic.

The choices are amazing out there. Some are very unique.

I tend to like mammal guide books because I enjoy studying mammals.

But, of course, bird guide books seem to the most numerous, with some narrower and narrower focussed populations.

Mostly, the track and traces field guides are best for fieldwork, and the rest are great for reading at home and being selective about what to take with you.

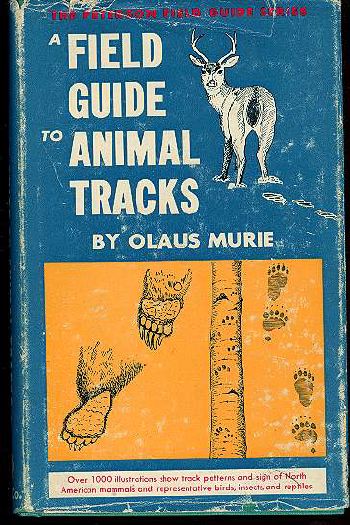

One of my favorites of all my field guides is Murie’s on animal tracks. My field-weary copy is not as clean and brand-new-appearing, as say, my field guide on lemurs (which I read in the quiet of my small book room) – for obvious reasons.

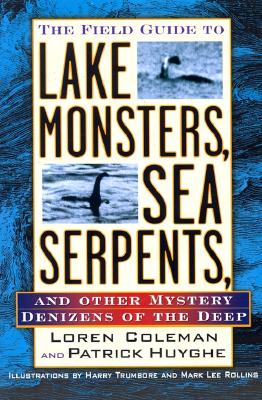

Within cryptozoology, there are only a limited number of choices, so there’s less a chance to be overburden with field guides. It makes me happy every time I hear that someone has actually used one of my field guides on an expedition. When I update the field guides, I list all the places that specific guide has been taken afield. And by whom. (Tell me of any such uses you know about, please.)

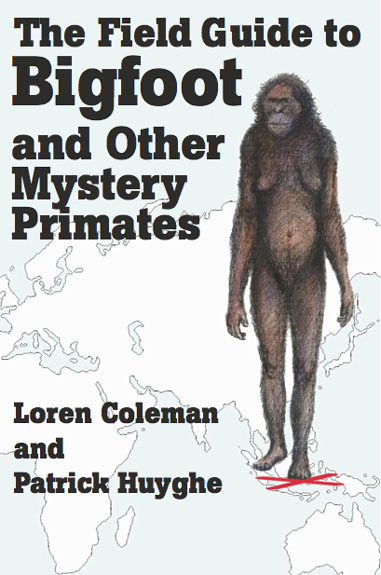

So far, my and Patrick Huyghe’s The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates has gone the most places ~ throughout North America and into the rainforests of Africa and Oceania ~ often being employed by researchers as a visual aid for use with indigenous peoples.

This info has been rewarding to learn.

What are your favorite non-cz field guides?

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

I’ll be looking forward to your new field guides when they come out!

Ah, I spot the venerable Peterson guide! That brings back some memories!

Know the flora and fauna and spoor of the area of your field research very well, so that if something is out of place, it will pop out at you. Have a reliable (non-hoax-oriented) rural local with you, who has such good environmental awareness, that they can tell as soon as something has changed in the vicinity.

Be very quiet and low impact concerning scents, sounds and lights.

Dusk and dawn are the times when animals are on the move, both diurnal and nocturnal. Those are the prime times to look, not midnight. Full moons are ok, too. Deer can be on the move then.

Call-blasting always sounds wrong because you can hear the effect of the loudspeaker on the sound. If Napes exist and are smart, they will be wary of such sounds. Not to mention that the loudness is unnatural.

In the case of Orang Pendek and the presumed area of activity on that one volcano, the search party should surround the base and work its way up (or surround it with camera traps that cover each other) so the troop won’t simply melt away into the forest ahead of you, so that you never see them.

I have a late-’90’s edition of The Peterson Field Guide to North American Mammals, and it is absolutely invaluable for identifying different mammals AND their tracks. When I was a kid, my grandmother had some field guides to insects and reptiles, but I don’t remember if they were Peterson’s or not. Good article, Loren.

For bird ID, I swear by the Sibley guide, but the Peterson and the National Geographic books are also excellent. For herps, my favorite is the Peterson (Eastern region), and I also have the Audubon Society guide, the Alabama guide by Robert H. Mount, and “Florida’s Snakes” by Bartlett and Bartlett. I also have the Peterson and Princeton mammal guides, the Peterson and Audubon butterfly guides, several fish guides including two huge volumes of Alabama freshwater fish (these are too big to really be considered field guides, however), and the Princeton guides to dragonflies and caterpillars. Oh, and last but not least, “The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates”!

I updated this entry with more info on the searchable University of Illinois-based website, International Field Guides.

Loren,

Thanks for the article. You just sold one copy of the Exotic Animal Field Guide off Amazon to me. Hadn’t heard of it before. Looks really interesting. Thanks again.

In my opinion the Peterson guides are the best general guides around. Much better then Audubon. I compare the two because they are both popular and cover a range of subjects. The Audubon guides don’t cover all species. I realized this when comparing their guides to freshwater fishes. Audubon doesn’t have nearly as many species while the Peterson covers all the species in North America (north of Mexico). Audubon also neglects to cover differences between juveniles and adults and non-breeding versus breeding adults. I noticed this also when trying to ID waterfowl with my Audubon that they don’t cover all the various stages of molting or what have you. And some of the photographs don’t help you identify squat. As for other guides the Sibley guides are good, I have their guide to marine mammals and it covers all known species. If you can get them state specific guides are great. I cannot imagine not having my “Inland Fishes of NY State”.

As for cyptozoology guides they aren’t something I carry into the woods with me. If I see a sasquatch I don’t think I’ll need a book to figure out what it is! I do enjoy reading them though and have Loren’s mystery primate guide. I’m really looking forward to getting the lake monsters and sea serpents guide.

The Sibley Guide to Birds is the preeminent bird guide. I’ve never seen anything close. All the info, one page, with great illustrations and easy lookup. Now it’s a bit huge.

But I’ve found that I don’t carry guides into the field with me much anyway. With birds at least, I think it’s better to burn the image of the bird into your brain, scanning for anything that looks like a unique identifier, then look it up when you get home. Too often, before doing this, I went…it’s grey…[fumbles for guide]…it’s smalll…[flipflipflip]…it’s….gone….

I’m not a track person, not as a specialty, but the Olaus Murie track guide in the Peterson series, seen up there, is not only comprehensive but a lyrical read, with evocative illustrations of the trackmakers.

And, while I won’t be taking it with me in the woods for the same reason maslo63 cited here, Gordon’s “Field Guide to the Sasquatch” is a very good, albeit quick, read.

Well, if you are interested in reptiles or amphibians, and you ever plan on being out in the field in Japan, you can’t really go wrong with the “Field Guide to Japanese Reptiles and Amphibians” by Richard C Goris. It’s an English language guide and provides the Japanese (written in Romaji, or the roman alphabet, for those of you who can’t read Japanese) as well as the English names for the myriad species to be found throughout the Japanese islands, many of the species being endemic and found nowhere else on Earth. If you’ve ever been interested in seeing just how remarkably diverse the reptiles and amphibians are over here in Japan, I’d recommend giving it a look.

Maybe someone should start converting all these valuable fieldguides into a digital format, so researchers can carry all the info inside PDAs or laptops. Imagine having you Ipod touch filled with all the images and info of a 1000-page book!

Hey Loren

I put a plug in for your field guides in my recent LiveScience column.

I was trying to help you out, though the LiveSci editors– not me– wrote the headlines and subheads, so it wasn’t me who mentioned the word “fake.” As you know from our discussions, I have long disputed the utility of a “field guide” to creatures not known to exist, but I wouldn’t call any guide to cryptids as “fake.”

Thank you, Ben.