Addax to Zebras: Mungall’s Exotic Animal Field Guide

Posted by: Loren Coleman on April 28th, 2008

Life works in strange ways. So does death. Good things can come from appreciating the moments that issue from both.

Cryptozoologist Scott Norman’s and then my crypto-supportive mother’s separate sudden deaths within a forty-day span gave me pause recently to slow down a bit.

Between the two events, I kept writing at a busy pace and conducted my “Pinkie” expedition to Florida. I also traveled to various locations to give cryptozoology talks, but I additionally wanted to take some quiet time for myself to visit animal parks and zoos.

I’ve always found such gems in the midst of human habitats to be mental and connective respites, allowing me to realign my zoological zen. This year already, I’ve taken side treks (while fulfilling other commitments) to tour the Central Park Zoo in New York City, and the Sanford Zoo and Gatorland in Florida. Most recently, I’ve visited the Stone Zoo outside of Boston and the Lupo Zoo in Ludlow, Massachusetts.

At the Lupo Zoo, my curiosity was aroused by one of the displays on the enclosure for the nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus). I knew this to be an antelope found on the Indian subcontinent, so I was taken aback somewhat by the distribution map shown. It clearly mapped the nilgai’s range in India, but also pointed out a widely dispersed “introduced” population in Texas, there since the 1970s. I understood some were on private ranch complexes down there, but what struck me was a shift in the paradigm for conceptualizing where they are living.

Of course, I thought to myself, that’s certainly another way to begin to think about such populations in North America. People have noted “introduced” birds for years, and English sparrows, starlings, and other birds are now in some field guides for this side of the ocean. In 1973, I did a massive survey of all the introduced and wild populations of primates in North America, highlighted by the rhesus monkeys of Silver Springs, Florida, but also keyed to various wild squirrel monkey groups in the United States and reports of feral baboons along the Trinity River in Texas. I presented that paper at the University of Illinois, but I’ve not seen any comprehensive effort to map these feral primates since then, as such.

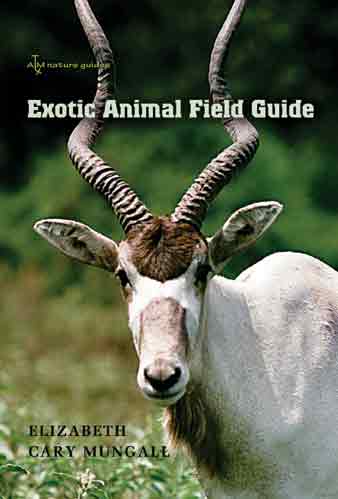

The nilgai map incident, however, set me to slow down, find, and take the time to read an important book recently published: Elizabeth Cary Mungall’s Exotic Animal Field Guide.

Mungall’s field guide does what any cryptozoologist should congratulate in a field guide of exotics, she has systematically overviewed a group of large mammals, many of which are free-ranging in America.

Specifically tied to nonnative hoofed mammals, Mungall in her new book captures in one place a great analysis of where to find, what to look for, and what viewed behaviors to expect from the 230,000 or more large foreign hoofed mammals that live in the United States. These animals are native to other locations from Africa to Asia, but today can be found in Texas, Florida, New Mexico, Maryland, California, New Hampshire, Hawaii, and other states on ranches, in wildlife preserves, at zoo-linked safari parks, or “just behind high fences or on a mountainside along the byroads of America.”

The book is filled with wonderful photographs, and for photographers, it is a handbook on how to take and what equipment to use to get outstanding images of these animals. “Photography Basics for Exotics” by Christian Mungall is a 20-page-mini-book within this book, and instructive for anyone considering taking good photos of animals or cryptids.

I found Elizabeth Mungall’s discussion of the historical background in her chapter on “Where to See Exotics” very insightful on the “whens” and “whys” of some of these species, which were re-located to the Americas. Oftentimes hunting was behind it, but sometimes other reasons were there for those that have liked to have exotics on their land. Today, a strong underlying theme is the conservation movement, with endangered species being bred here and used to restock depleted native lands.

The field guide section that profiles the species breaks down along the lines of what deer, antelopes, sheep/goats, cattle, and other animals are to be found in the USA today. The guide features eighty different kinds of hoofed mammals, from the common ones, such as blackbuck antelope and fallow deer, through the more uncommon kinds, like the scimitar-horned oryx and a few newer arrivals like defassa waterbuck.

The sections are hardly boring, and for example the “Cattle” subsection includes the African Cape buffalo, banteng, gaur, water buffalo, and yak, which are roaming in America’s open spaces. The “Other Animals” subdivision details various kinds of camels, giraffes, rhinos, and zebras, as well as llama and wild boar.

Each individual description of the species includes the native range maps and information about food habits, habitat, temperament, breeding and birth seasons, as well as fencing needs (oriented to those interested in keeping these animals). I especially liked reading the paragraphs on “species compatibility.” For example, I would speculate there are only a few other field guides that you have read where you can find sentences like this one (p. 159): “Nigali bull will kill eland bull.”

Or, when discussing the sable antelope (p. 173): “Male my injure or kill maturing males and even sable female strangers, plus other species (like greater kudu and waterbuck), including humans.”

Or about the breeding of sitatunga (p. 175): “Hybrids with many spiral-horned antelope (lesser and greater kudu, bongo, nyala, bushbuck, and eland – eland sire lethal.)

The field guide is broadly useful to those wanting to observe these animals, those thinking about keeping them, or merely the casually interested natural history buff. For individuals who wish to get more deeply involved, there are a list of exotics-related organizations and a reference section of other sources and books at the end.

Although I know exotics exist in the Americas in a wide-variety of sites, my one wish, regarding the individualized descriptions, is that the profiles would have been enhanced by including suggested locations for the best concentrations of where that one specific type of animal could be found. Location information is under Mungall’s subsection to “Where to See Exotics,” but it is diffuse and incomplete as far as individual species. If such locale-specific data could have been tied at the end of each of the 80 species’ profile to a few recommended ranches, wildlife parks, or preserves each that would have been outstanding.

But this a minor point, which does not distract from an enjoyable and thoroughly useful field guide that should be carried by every traveler and observer to such sites throughout the USA. It is an invaluable key to identifying sometimes confusing lookalikes among the hoofed mammals.

Mungall’s book is highly recommended for cryptozoologists who wish to be aware of what large exotics you may have in your area, and for anyone that enjoys zoologically interesting large mammals. Being a collector, reader, and author of field guides, I say, this one is a must-have for everyone intrigued by large out-of-place exotics and cryptids in North America.

+++++++++

Wildlife biologist Elizabeth Cary Mungall is an adjunct professor at Texas Woman’s University, Denton, and a wildlife research consultant for the Exotic Wildlife Association. She lives in Houston and teaches classes at the Houston Zoo.

Exotic Animal Field Guide: Nonnative Hoofed Mammals in the United States

978-1-58544-555-4

(1-58544-555-X)

flexbound with flaps

$23.00

LC 2006014549.

5 3/4×8 1/2. 312 pp.

234 color photos.

82 maps. 2 b&w illus.

4 tables. Bib. Index.

Natural Science.

First published: March 2007.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

For years there was a breeding population of markhors, a type of wild goat, that lived in the cliffs near Delbarton, WV (about 20 miles from my home).

I often saw them and they were local “celebrities.” I have not seen any in a long time. There was talk of destroying them since they were nonnative; I don’t know if that was done.

Sounds like a great field guide to have. A good friend of mine used to be a zookeeper of large mammals and hoof-stock at the Houston Zoo, I will be sure to pass along the information on the book to him.

Some friends of mine actually have some of the blackbuck antelope and fallow deer on their property out in Leaky (lay-kee), Texas. Beautiful animals.

There is also a “buffalo farm” of sorts out IH-10 west of Houston, the name escapes me; it also appears to have antelope, at least from what I can tell driving by at high speed. I have passed it several times and I hope to be able to stop by one of these days to take a closer look.

Thanks for the info on the book!

Yep, that’s what they looked like. The markhors, I mean. The males were really big, maybe the size of an average Shetland pony (though maybe not as heavy), and they had long, flowing beards and lots of shaggy hair in sort of a mane along their necks and bellies, and huge spiraling horns. I used to see a small flI think that they were imported by some coal baron about a century ago for sport hunting, at least that is the story, and then they either escaped or were abandoned and went wild. ock of them along US Rt 52 in the cliffs created by the road cut.

When the Hatfield-McCoy ATV trails were in the planning stage, some folks thought that the markhors should be destroyed since they are not native. I thought that was ridiculous, because they had naturalized and become established, and they were not invasive at all. They had lived there for so long that some people thought they were part of the native fauna. As I recall there was a lot of outcry against destroying them, even though they are not native, because they are endangered. There was talk of trying to capture and relocate them. I do not know what the final resolution was, and I can’t find anyone who does.

My guess is that they were killed. I have not seen any for about ten or fifteen years, and I’m over that way at least two or three times a month. I used to see them almost evey time I passed through there.

I also had a recent trauma (car accident – almost lost arm). While recovering I decided to go to the zoo (I am a animal person). The day turned out to be one of the most tranquil and life refocusing days in many many years.

I spent about one hour just sitting and watching the meercats watching me. I still look back to that day (a year ago) and plan to go again by myself again and not wait another 40 years.

Elizabeth Cary Mungall co-wrote with William J. Sheffield, copyright 1994, a more detailed work entitled Exotics on the Range: The Texas Example, along these same lines. It was published by the Texas A&M University Press.

Included are maps of Texas broken into counties showing the then-reported distribution of the exotic hoofed livestock. It is a large format book, 265 pages long, with some color pages illustrating the exotics as well as some black & white photos. It covers both the animals’ natural history, as well as other topics such as hybridization of exotic species (zebra species hybrids, for example) as well as hybrids between exotics and domestic livestock, the commercial hunting of these exotics and so forth. It is quite a book with lots of detailed information in it.