Top Ten Cryptid Ungulates

Posted by: Loren Coleman on July 7th, 2010

Top Ten Cryptid Ungulates

© Loren Coleman

The poor brothers and sisters of cryptozoology are the hoofed animals, cryptids that don’t really scare anyone. They are four-legged unknowns that eat plants and, well, just aren’t sexy. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore them.

Here are some basics so we can all start out on the right hoof, I mean, foot.

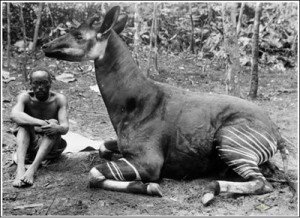

There are two groups of ungulates. The even-toed hoofed animals (Artiodactyla) include pigs, hippopotamus, camels, giraffes, okapis (one is shown above) and antelopes. The odd-toed ones (Perissodactyla) include the horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Obviously, a cryptid is something that only foggily can be identified, and even trying to classify them into a cryptid category is quicksand. But we try, because if cryptozoology is to be helpful, we need to organize around some generalities, which will influence where cryptozoologists look, what zoologists might wish to study, and which behaviors mammalogists may want to consider.

Success stories have come from the annals of new species discoveries of the hoofed animals, with the okapi being one of the most notable. Also worthy of mentioning is the pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis or Hexaprotodon liberiensis) found, cryptozoologically, by tracking down native tales and other signs.

Karl Hagenbeck, a famous German animal dealer, established a zoological garden near Hamburg, the prototype of the modern open-air zoo. In 1909 Hagenbeek sent German naturalist-explorer Hans Schomburgk to Liberia to check on rumors about the nigbwe, a “giant black pig.” After two years of jungle pursuit Schomburgk finally spotted the animal 30 feet in front of him. It was big, shiny, and black, but the animal clearly was related to the hippopotamus, not the pig. Unable to catch it, he went home to Hamburg empty-handed.

In 1912 Schomburgk returned to Liberia and, to the dismay of his critics, captured a pygmy hippopotamus on March 1, 1913, and then returned to Europe in August with five live pygmy hippos.

(A full-grown pygmy hippopotamus weighs only about 400 pounds, one-tenth the weight of the average adult hippopotamus.)

But all such discoveries among the hoofed animals do not become celebrities. Take, for example, the rather forgotten case of the Chacoan peccary.

This “rangy big pig,” as University of Connecticut biology professor Ralph M. Wetzel characterized his 1974 discovery, was a big surprise — a Pleistocene Epoch survivor of a species thought to have died out 10,000 years ago. The Chacoan peccary, a relative of pigs, boars, and warthogs, weighed in at more than 100 pounds, the largest and most unusual of the known peccaries. Wetzel found it in the wilds of Paraguay, South America, after interviewing the natives about a mysterious pig variously called tagua, pagua, or cure’-buro (“donkey-pig”).

Wetzel stated that it differed from other known peccaries by its larger size; longer ears, snout, and legs; and proportionately shorter tail. In 1975, Wetzel formally named the species Catagonus wagneri, the Chacoan peccary or tagua.

Karl Shuker in his The Lost Ark, adds an ironic twist to the story: “Following its ‘official’ return to the land of the living, news emerged that for a number of years prior to this, and wholly unbeknownst to science, its hide had routinely been used by New York furriers to trim hats and coats.”

Another more classic and well-known example is the giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni), ranging today from Liberia to Kenya, Africa. First reported by natives to Europeans back in the 1660s, the world’s largest pig was “discovered” by Western science, in East Africa in 1904, when Lt. Richard Meinertzhagen brought the first one out. The forest hog reaches seven feet in length and more than three feet at the shoulder.

At the other extreme, the pygmy hog (Sus salvanius), the world’s smallest pig (two feet long), was declared extinct in the 1960s. However, it was rediscovered by Dick Graves, in 1971, in the Indian state of Assam.

We thus jump in with both feet, and venture into the shadowy world of hoofed cryptids left neglected for too long on the lists of significant and interesting cryptids. I share some unknown animals with you, of which you have heard little.

My fellow associate and friend, British cryptozoologist Karl Shuker is famous for discussing cryptids other than the hairy hominoids and he’s been doing some outstanding work documenting for years these animals that he likes to call crypto-ungulates. This list of my own top ten favorites is dedicated to him.

1.

Quagga:

This horse, a variety of zebra actually, is an attractive and known animal that supposedly went extinct, but some 19th century authors and a few modern cryptozoologists feel it may still exist. Found in South Africa, it is distinctive because it most often had stripes over half its body, the back half. The rest of the body was yellowish or brownish, and the zebra-type stripes were a darker brown (but not black).

Cryptozoologists Bernard Heuvelmans wrote in 1986 of there being occasion Quagga sightings in the Namibian desert, despite the fact the last one in the wild went extinct around 1875. The last Quagga to die in captivity was one at the Amsterdam Zoo on August 12, 1883.

2.

Emela-ntouka:

Among several different kinds of alleged “dinosaurs” in Africa, one animal is called by locals the emela ntouka, or ‘killer of elephants.’ The semi-aquatic Emela-ntouka is described as more rhinoceros-like than the Mokele-mbembe, almost as large as an elephant, reddish-brown-gray, hair, with a single horn that protrudes from its head, and very uniquely, a large heavy tail. It roars.

The stories have been around for a long time. Explorer and animal collector Hans Schomburgk collected stories in 1913, from the Klao tribe of a small rhinoceros found in the mountains of Liberia. Reports of a forest rhino in the Republic of the Congo were heard at Kellé in 1950, and photos of 10-inch-wide three-toed tracks on a riverbank at Loubomo in 1966.

In 1981, Dr. Roy Mackal while searching the Congo for the Mokele-mbembe, collected accounts of these Emela-ntouka. The natives in the northwest region of the Likouala (M’boshi) swamp told him that this animal would gore elephants with its single horn. Mackal initially considered that Emela-ntouka might be a Centrosaurus (”pointed lizard”) of the Ceratopsian family (formerly the Monoclonius). But he also noted the pygmies did not report a neck frill, which he would have expected on a ceratopsian.

I have long speculated, in agreement with early 20th century wildlife officials in the area (especially Lucien Blancou), that the Emela-ntouka there might be an unknown new subspecies or species of aquatic rhinoceros in the Cameroon-Congo area, captured in the folklore of the Emela-ntouka.

3.

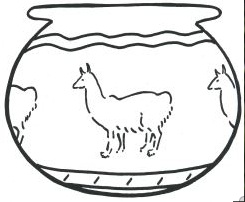

Five-toed llama:

Llamas are usually two-toed, but in the 1920s, evidence began to surface that a five-toed llama co-existed in Peru with humans. Pottery fragments from the Paracas near Pisca, Ica, Peru, set at between 600 B.C. and 200 A.D., collected by Julio César Tello, showed painted depictions of a llama with five toes. He also found bones he believed were from the five-toed llama. While no modern sighting exists, it is an intriguing thought that humans may have known a completely unknown llama.

4.

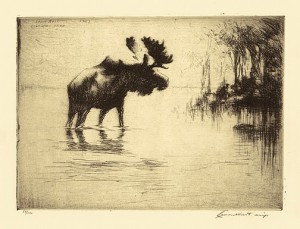

Mystery Moose

Is there a larger than normal variety of Moose in New England, North America?

See here, for more on the Mystery Moose.

5.

Noyon Uul Musk Ox

The Musk Ox is known today only from Greenland and northern North America, although formerly they lived around the crown of the globe. Was or is there a survival of the Musk Ox in Asia, specifically in the mountains of Mongolia and north-central Siberia? Could these large huge hairy beasts still be in remote corners of Mongolia?

In 1924, two silver plaques dug from tombs from the 1st century in the Noyon Uul Mountains, Mongolia, show clear carvings of a Musk Ox. How could this be? They supposedly had died out in Asia 8000 years ago. But then, in 1948, Musk Ox skulls from 1800–900 B.C. were discovered on the Taymyr Peninsula, Siberia, as well as sub fossil skull in 1984 near the same site. The 1948 skulls had holes in them, as if drilled by humans.

6.

Pukau

Said to look like a cross between a pig and a deer, it has been seen running around the slopes of Mount Madalong, in Sabah state, Borneo, Malaysia. Strangely, it is described with a “sharp tongue.” It is mostly reported among the Saiap Dusuns natives.

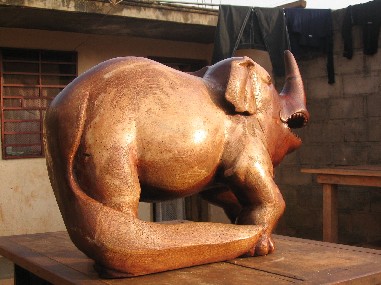

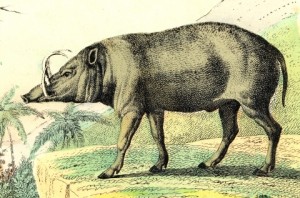

Cryptozoologist Karl Shuker wonders if it is the babirusa (“deer-pig”) ~ shown above ~, a known wild pig, whose curved tusks might be described as a sharp tongue and found only on Sulawesi, Buru, and neighboring islands, might be the Pukau. Did an ancient land bridge population these islands with similar wild pigs, including the Pukau in Borneo?

7.

Schomburgk’s deer

Supposedly extinct in the wild of Thailand since September1932, there could be some relicts of this form of deer in Laos. A surviving population of this deer appears to have been reported in Laos. It has been presumed extinct in Thailand since 1940, when an intoxicated villager killed the last captive specimen at a temple.

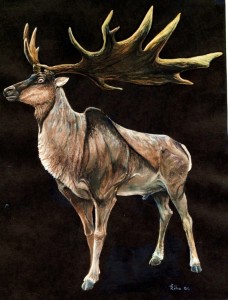

A beautiful chocolate-brown deer with antlers that sometimes hold up to 33 points, it can be six feet long and between 3-4 feet high at the shoulders. In 1991, a rack of antlers from an animal killed in 1990 were discovered by agronomist Laurent Chazée in a Laotian medicine shop Present status:

8.

Schelch.

The German word for this cryptid (which is sometimes called Shelk) is said to be a Central European Giant Deer of Austria reported mostly in the Middle Ages, or the Irish Elk in Ireland.

The Giant Deer are found on Upper Paleolithic (25,000–12,000 years ago) cave art in France and Spain, and 6th century Black Sea Scythian artifacts that seem to show these animals.

In a related sense, the giant black deer, often called the Irish Elk, seems to have survived to be known by ancient Irish peoples who used their skins for clothing, milk, and the body for meat. Human bodies found in bogs in Ireland have Irish Elk hair on them.

9.

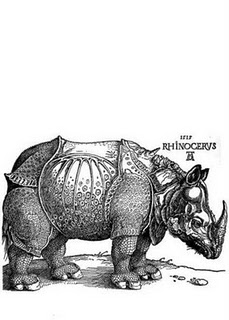

One-horned African Rhinoceros

This unique rhinoceros are reported in East and South Africa. The rhinos in Asia have one or two horns, depending on species. All of the known African rhinos have two horns. What is this one-horned rhino doing in Africa?

Apparently, with records in Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Chad, northern Mozambique, and northern South Africa, the One-horned African Rhino is widespread but unverified. Cryptozoological archivist George Eberhart reported that a small, gold-plated artifact – dating from the 12th century – depicting a rhinoceros with a single horn was discovered at the Mapungubwe archaeological site, Northern Province, South Africa. Sightings of this One-horned rhino took place in the first half of the 19th century in sub-Saharan Africa.

Eberhart observed in his encyclopedia Mysterious Creatures: “The two extant species of African rhinos have two horns. The Black rhinoceros lingers tenuously in widely scattered pockets of East, Central, and South Africa; the White rhinoceros is now limited to KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa, and the borderlands of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, and Uganda. For the most part, rumors of a one-horned species exist in areas that are no longer part of either species’ range.”

10.

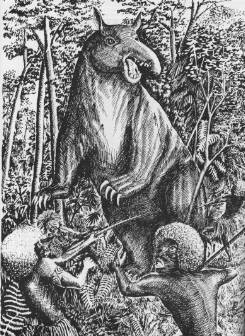

Gazeka

Looking pig-like, this unknown animal seen in the Owen Stanley Range, Papua New Guinea may actually be a new type of tapir. It has patterned marking on a dark skin, but is big for a jungle pig at five feet. It reportedly has a horse-like tail, long snout, and cloven hooves.

Explorers on the northeast coast found fecal material the size left by rhinos in the 1870s, and eyewitnesses saw this creature on Mount Albert Edward in May 1906. Finally, a remarkable stone figure was found in 1962 in Papua’s Ambun Valley, which appears to show these cryptids, complete with long snouts.

Which cryptid ungulate will be found first?

+++++++++

Keep the Quest Alive!!

Please, if you can, do…

Thank you, and come visit the museum at 661 Congress Street, Portland, Maine 04101.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Loren, I love the website and I am really interested in this article.

Really excellent article on the ‘less sexy’ cryptids. It’s good for all of us to step back from the Bigfoot/Sea serpent circus once in a while and realize all over again that there is truly more in the world than we can ever dream. Thank you.

This is a great article. I’d forgotten some of these.

I was surprised, though, at two that were not here. John MacKinnon, on the same expedition that led to the discovery of the saola, found in a museum in Hanoi the horns of two unknown species of deer, known locally as the “black deer” and the “slow-running deer.” So we have two ungulates for which hard evidence is in hand, but no one seems to be looking for them. I’d think they’d be at the top of any crypto expedition’s wanted list.

IDK about you guys but that 5 toed Llama is sexy as hell! I hope that one is found first.

Wasn’t there an effort to revive the quagga with DNA taken from a specimen and using a horse or zebra to incubate the fertilized egg? It was quite a while ago, and apparently never made it. Then there was also the man who tried to breed zebras back to their original ancestral animal, which was an ordinary dun-colored animal with no distinctive markings.

Matt makes a good point. Certainly the most likely new ungulate to be discovered will occur in south-weast Asia. Of the ones listed, the rediscovery of Schomburgk’s deer would seem to be the best bet.

Can predict the least likely to be rediscovered on the list, the Irish Elk. For a variety of zoological, botaniacal and geographic reasons, that animal is extinct…forever.

Love that photograph of a “giant” okapi.

Loren, I second the appreciation of a post like this about what some may consider the more mundane cryptids. This is great.

Least likely to be found? Well, I see your point on the Irish elk, but the Magnificent Mystery MegaMoose doesn’t seem too likely either. Unfortunately.

I’m surprised the kouprey isn’t in this list.

It is real; it exists. Or did. No one knows; the last photographic record from the wild is from 1981 (and that is one of the few records there is).

Some compelling sighting reports have come in since. But no one knows whether this very real animal is still here or not.