Yeti Coneheads, Scalps, and Skullcaps

Posted by: Loren Coleman on April 11th, 2012

Our Snowman buddy Henry Stokes over at “I Love The Yeti,” asks the universally, frequently-heard question: “Why are there so many Yetis with cone-heads?”

Then, immediately, he answers that inquiry with this: “It’s all because a scalp thought to be from a Yeti was discovered in a Buddhist monastery in Pangboche, Nepal in 1954. It was pointy.”

That answer rings true today, due in large part to the midcentury Western discoveries that caused an immediate cultural sensation, up-to-a-point (every pun intended).

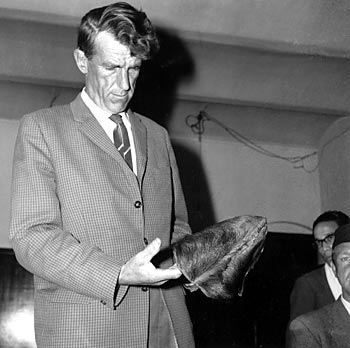

The Pangboche “skullcap.” 1954 Daily Mail Expedition.

The Daily Mail‘s Snowman expedition of 1954 revealed that the Pangboche and Khumjung monasteries housed ritual objects “made in imitation” of the supposed skull structure of Abominable Snowmen or Yetis. Due to the Western and Japanese search parties that then went looking for the Yetis, especially from 1954 through 1960, the image of the Snowmen began to conform in appearance.

The International Cryptozoology Museum displays a Jeff Meuse replica of the Pangboche skullcap, in tribute to these relics.

How were these relics employed, at the time, in reconstructions of what Yetis were thought to look like?

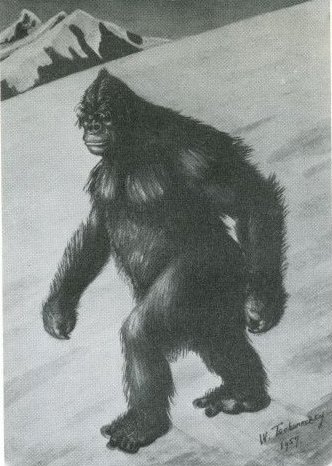

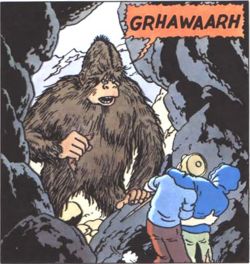

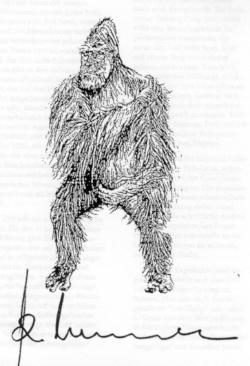

Wladimir Tchernezky in a 1957 drawing that appeared in books about the Yeti, from 1958 through 1961, reinforced the image of a giant Snowman with dark hair (as seen by the locals) having a pointed head (as sighted in life and shown in the imitation relics).

Tchernezky drew the head based on the “scalps,” as he indicated in his writings.

Then a World Book’s artist completed the same illustrative exercise leading up to the 1960 expedition.

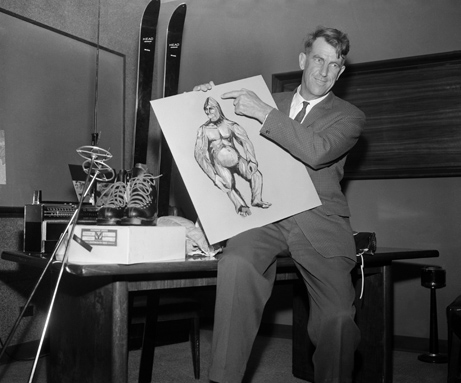

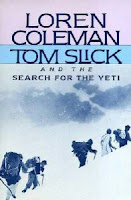

To prepare for their excursion to the Himalayas in search of the Yeti, Sir Edmund Hillary and Marlin Perkins of the Lincoln Park Zoo (later director of the St. Louis Zoo) quietly talked to such cryptozoological figures as Tom Slick and Bernard Heuvelmans. They based their press conference materials on the growing notion of what a giant Yeti looked like.

The illustration of the Abominable Snowman that Hillary used during his Chicago news conference closely matched the general version acknowledged by Heuvelmans and Ivan T. Sanderson. It was seen as nearest to the appearance of the man-sized Yeti, the Meh-Teh.

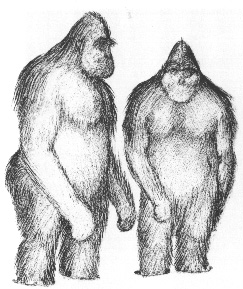

In Europe, Heuvelmans was using a version of the following Yeti drawing.

This continued after the expedition returned. Marlin Perkins was the host of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, a program that premiered after the Hillary-World Book-Perkins expedition came back from Nepal. The show soon broadcast an episode on the Abominable Snowman. Perkins is shown famously standing next to a full-scale cutout of the Yeti image similar to the one displayed above by Hillary. The drawings used by Hillary-Perkins merged with those of their contemporaries.

In late 1960, upon his return, Sir Edmund Hillary overtly ignored (to the media) what was already on the record regarding the “scalp” relics being copies of the real Yetis’ heads. He dramatically brought back the Khumjung “scalp” to “disprove” the legend of the Abominable Snowman. Of course, he knew what the results were going to be from the testing, as he was carrying around in an attache case a new “Yeti” skullcap he had had made from a serow skin before he left Nepal for Europe. But, nevermind, illusion is half the battle in media events. If you are using Yetis to coverup an intelligence-gathering mission observing rockets flying out of China, misinformation is the name of the game.

Next, Heuvelmans’ drawings and the Hillary expedition images influenced the artist Herge and his midcentury illustrations of the Yeti.

The classic detailed comic book Tintin in Tibet in 1960, for example, showed the pointed head of the Yeti, as found on those “skullcaps” discovered in the early 1950s by Western expeditions. These imitation-Yeti ritual artifacts, said to be 350 years old, were in the possession of the lamas of Nepal and, reportedly, in Tibet, as well. Expeditions in 1954, 1957, 1958, 1959, and 1960, talk the most about them.

After the early 1960s, Yeti sketches continued to evolve through the representations of recent artists who modeled their Yetis on the older images and history of sightings.

Harry Trumbore’s drawing of a Yeti, as it appeared in my 2006 field guide, echoes the 1960s’ image of the Abominable Snowman.

But wait, was this pointed head imagery there long before the 1950s and 1960s?

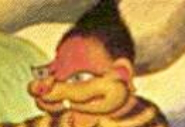

Let’s look a bit further back. Bhutanese and Nepalese imagery reflects the pointed or conical nature of the Yeti head in ancient art.

Bhutan’s modern stamps have published old art with the pointed head of the Yeti.

Nepal’s Kathmandu Temple art of the Chuti-Yeti shows a similar head.

Were heads like these seen in the surrounding mountains of Asia long ago?

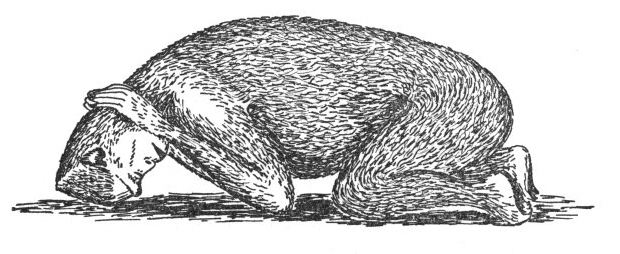

In 1913, a Moscow-based professor of comparative animal anatomy named V. A. Khakhlov submitted a full and detailed report on the East’s “Wild Men” from Dzungaria to the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. Researchers often recall it for this following drawing of a hairy hominoid’s sleeping position. But examine that head.

A drawing made by Prof. Khakhlov of the Almas-type of Abominable Snowman from native descriptions. From Ivan T. Sanderson’s book Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life.

Below, the inverted, upright look at the Khakhlov creature’s head and its pointed top, compared to Tchernezky’s drawing of the Yeti head.

The cover of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life uses the Shipton tracks to the extreme right, and on the spine of the book reproduces a mask that interested Ivan.

The strong imagery of this representation of an “Abominable Snowman,” for Sanderson was evidence of the peaked head of these creatures. Sanderson included a reconstruction of what this hairy hominoid might have looked like in life.

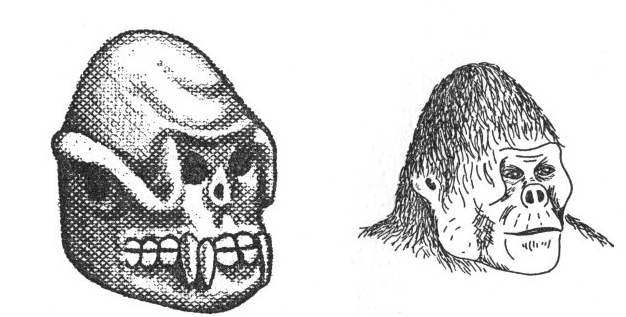

(Bottom, left) An ancient mask from the great Mongolian plateau. (Bottom, right) Reconstruction of head and face of the creature on the mask, drawn by Russian scientists.

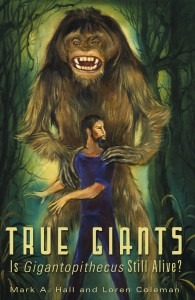

The drawing of the mask is used as a chapter icon throughout True Giants: Is Gigantopithecus Still Alive?, as, indeed, the mask may have been a significant representation of Gigantopithecus.

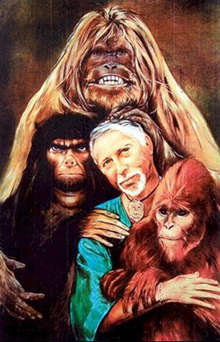

It is a full circle traveled, for in Bernard Heuvelmans’ thoughts on Gigantopithecus he sees it as the source of Yeti accounts. These then influenced his own sketches and those from Alika Lindbergh (below) of how these “friends” of Bernard’s would have appeared, right down to their pointed heads.

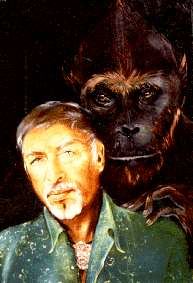

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Let’s play devil’s advocate here for a while, and speculate that the traditional representations of the Yeteh were inspired by religious iconography. Indeed, one can find many examples in which lamas are adorned with pointy hats, which give them a somewhat ‘Yeti-esque’ appearance.

[Art/graphics admin. modified due to size limitations in comments.]

Perhaps, since the Yetis were seen as an important element in the Nepalese traditional belief system, they (the Nepalese) felt the need to honor them by way of portraying them with a similar feature–although a natural one in their case.

Of course, I’m fully aware that this speculation can be reversed, and one could argue that it was the pointy skull of these creatures what inspired the people living in those areas to start wearing pointy hats in the first place.

Or maybe the Yetis come from France 😉

It might be worth noting this 1961 major release of The Abominable Snow Rabbit. The head is notably flatter…