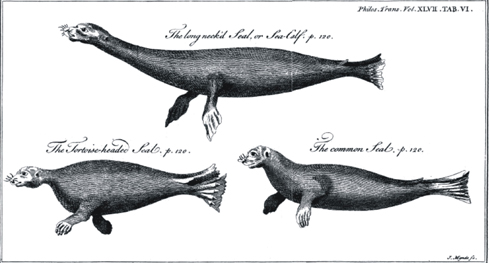

Long Necked Pinniped, Parsons 1751

Posted by: Loren Coleman on September 26th, 2008

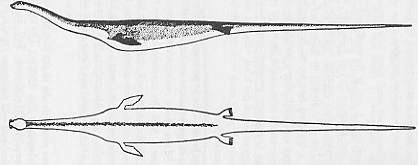

Before there was Bernard Heuvelmans’ long-necked Megalotaria longicollis, or my and Patrick Huyghe’s ideas, C. A. Oudemans proposed in 1892, in his masterwork The Great Sea Serpent, the species Megophias megophias, an immense long-necked, long-tailed pinniped. Oudemans’s reconstruction of Megophias is above. (Oudemans also extended this long-necked pinniped theory to what he felt were living in Loch Ness, in his next book – a small pamphlet, actually.)

Images of Sea Serpents appeared often, during the 1700s and 1800s, to reinforce the learned thoughts on this cryptid.

Now comes a remarkable discovery.

With congratulations, I applaud Darren Naish, who brings to our attention that…

…a Long-necked seal was described in the literature long prior to the work of Heuvelmans or even Oudemans. Reporting the observations of a Dr Grew on the Long-necked seal observed ‘in diverse countries’, James Parsons (1751) included an illustration [shown above] and description of this pinniped. He described how it was ‘[M]uch slenderer than either of the former [two other pinnipeds were described earlier in the manuscript]; but that, wherein he principally differs, is the length of his neck; for from his nose-end to his fore-feet, and from thence to his tail, are the same measure; as also in that, instead of his fore-feet, he hath rather fins; not having any claws thereon, as have the other kinds. The head and neck of this species are exactly like those of an otter. One of those, which is also now in our musaeum [sic], taken notice of by the same author, has an head shaped like that of a tortoise; less in proportion than that of every other species, with a narrowness of stricture round the neck: the fore-feet of these are five-finger’d, with nails, like the common seal. Their size, as to the utmost growth of an adult, is also very different. That before described, was 7 feet and an half in length; and, being very young, had scarce any teeth at all’ (Parsons 1751, p. 111).

Quite how a pinniped said at first to have a very long neck is then said to have a head and neck ‘exactly like those of an otter’ I’m not sure, and of course it’s not possible to determine whether this ‘long-necked seal’ has anything to do with Heuvelmans’s hypothetical animal of the same name. It’s tempting to assume that it was a confused description of a sea lion but, given that Parsons described a specimen 2.3 m long as a juvenile, it still sounds like an interesting animal that we’d like to know more about. To confuse things further, Parsons also mentioned a specimen which ‘is but 3 feet long, is very thick in proportion, and has a well-grown set of teeth’ (Parsons 1751, p. 112)….

The tantalising possibility remains that the larger specimen would have been significant in zoological terms, but given that we lack data on the provenance and fate of the specimens that were described by Parsons, any further comments would be entirely speculative. James Parsons, 1705-1770, was a British physician who studied medicine in Paris and later worked under James Douglas in London. As yet I haven’t done any research on the specimens he studied or wrote about, but this obviously should be done. What happened to his long-necked seal, and what was it?

Original source cited by Naish: Parsons, J. 1751. A dissertation upon the Class of the Phocae Marinae. Philosophical Transactions 47, 109-122.

Read all of Naish’s blog posting on this here.

Please note, while Darren is to be highlighted for his article, he also writes those who showed him the way: “I first heard of the article from Ben Speers-Roesch back when we were on the editorial board of the now defunct The Cryptozoology Review, and Ben in turn had heard about it from Scott Mardis.”

(Throughout this page, I have sprinkled various old wood carvings and other illustrations that may show alignments to or variations on Parsons’ long-necked pinniped.)

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Very interesting and compelling, but would they grow big enough to support the length reported in many sea and lake serpent sightings?

And why haven’t we found any recent remains? For that matter, seals aren’t exactly known for being reclusive animals. Wouldn’t they have been found long before now?

Could be an otter.

They also could have been open sea manatees or dugongs with the longer neck. They have been known to be a little shy. I have always wondered if any of the sea monsters were more mammal than reptile. I especially love the description of the ones living in North American lakes around Utah (I believe their description location starts at the Rocky Mountains and moves west). Basically they are suppose to have the face of a dog (ears included). That to me sounds more mammal. I wish I could go searching.

Playing with a little speculation here, maybe a long-necked pinniped would live only on the dark depths of the Arctic sea, using his neck to hunt for fish the same way plesiousaurs did. There’s of course the problem of coming to the surface for air; but maybe the glaciers have pockets of air trapped in holes that this animal could get to thanks again to the neck.

Who knows? Maybe with the Arctic ice melting down and more boats using it as a trade route, we’ll have more reports of long-necked cryptids in the coming years 😉

This is more circumstantial evidence that Heuvelmans was correct in his basic assumption–that almost all sea serpent sightings could be explained by unknown species of marine mammals, chief among them, a long-necked seal.

Sadly, one wonders if the thing hasn’t already gone extinct, seeing how sea-serpent sightings have dropped precipitiously in number over the years. Still, while I’m not up on recent ones (if any) I know there were a few tantalizing sightings from the sixties and seventies… though, again, one couldn’t be sure that the animals involved haven’t died off since then.

Would the existence of such an animal explain some of the lake monsters around the world? Eh. Maybe. Still, how a gregarious mammal could live in a confined body of water–or migrate back and forth between it and the sea–without making itself better known… I just don’t know. It seems very problematic to me.

I’m more interested, therefore, in the sea serpent phenomenon (rather than the lake monster one) from this angle. Surely, as Heuvelmans maintained, all these fairly similar sightings can’t be mere misidentifications, illusions, and hoaxes. To me this is the most exciting of all cryptozoological creatures, because it seems to most likely to actually exist. Bigfoot is a lot more sensational, but in the end he defies logic and reason on many levels (not that this means he can’t exist). But a long-necked pinniped—imagine centuries of mockery directed at the sea serpent being swept away by the discovery of such a pinniped; it would lend a great swell of legitimacy to this half-science we’re all so enamored of–and even though that doesn’t really matter so much, it would nevertheless be satisfying and would magnify the reputations of men like Bernard Heuvelmans and others like him—who deserve it, one feels.

A point here and there:

The accounts I’ve read of lake monsters in Utah do not impress – the Bear Lake creature in particular was a subject of really tall tales.

Bruce Champagne’s analysis of 358 sea cryptid sightings he thought impressive (out of 1247 he reviewed) produced the result that only 7% concerned longnecks.

That figure could be considerably off in either direction, though.

On the one hand, a few of those seven percent are very hard to dismiss: the SS Umfuli and HMS Fly cases come to mind (I am here presuming the Daedalus case to be either a giant squid (known type) or giant eel (unknown type) and the Valhalla case to be a giant eel, swimming as congers occasionally do with the head and forebody out of water. Just my opinions.)

On the other hand, it’s also possible that some humped or many-humped sightings could concern a longnecked animal that did not have its head raised at the time.

If the animal is in the habit of poking just its head out to breathe, it would not be seen often even when a ship is in the right position. Why it would have evolved that habit is a bit puzzling: its likely predators don’t generally hunt by using above-water vision.

It continues to bother me that I would expect an air-breathing animal to have suffered a few lethal encounters with whaling ships, or at least to be the subject of good sightings by whalers. There seem to be very few sightings and no kills or even harpoonings. (The Monongahela case sounds like a hoax. The captain’s speech about how the honor of American whaling men was at stake seems silly for any captain and ridiculous for a New England Yankee, for whom “Kill it” would have been a long speech.)

I will always wonder just what Dr. Parsons was looking at when he said he had access to a 7-foot juvenile specimen of a long-necked seal.

Concerning lack of sightings…I can’t remember who was the first to say it, but someone clever pointed out that most shipping that goes on these days in the oceans are along designated shipping lanes, so as to take the least amount of time.

Back in the 1800’s and earlier, when people were still exploring, ships covered a lot more ocean. Whether ships came across territorial areas where sea serpents frequented, or whether they crossed paths with sea serpents, who is to say.

But in the present, where so many ships follow shipping lanes, there are vast spaces where all kinds of critters may be that we are not.

In reference to MattBille’s question about sea serpents coming across whaling ships, there are actually a few odd encounters. I will try to find the reference, but I believe it was the mid 1850’s there was a ship’s log of a whaling captain who took down a serpent and brought it on board. I believe the captain reported that it began to stink, had very little usable material and was bothering the crew, and they ended up throwing it overboard, though I think the captain made sketches and took measurements of the critter. I don’t own the particular book, but it was a more obscure book on sea serpents which I checked out from our university library.

I think it also has to be kept in mind that we could be dealing with extremely rare animals here. There are some species of ocean going mammals that are known by only a single specimen. There are species of animal in the world that are so rare that they were not even ethnoknown before being discovered. Perhaps these creatures were even on the decline even way back in the 18th century. If these creatures were incredibly rare, this could maybe explain the lack of more sightings by whalers and why they have not been found yet.

I tend to think that most “sea serpent” sightings cannot be attributed to any one species. Sightings descriptions can vary substantially, as can the areas in which they were seen. For example, you get sightings in cold Northern waters as well as in the tropics. To me, this suggests that there are likely more than one unknown species responsible for sea monster sightings. Perhaps some were long necked seals, but I would guess not all. I do think that mammals are a good candidate as they are adaptable to a wide range of environments, and marine mammals have managed to fill many niches, but there could be large unknown reptiles or fish causing some of the sightings as well. I think there’s a chance that long necked seals are merely one among several species causing these types of sightings.

I also think many sea serpent sightings are perhaps caused by a mix of misidentifications, tall tales, and real sightings of a range of different known species as well. For instance, some sightings may be caused by unusual species such as oarfish or giant squid, or maybe out of place animals such as an anaconda or salt water crocodile far from shore or an animal outside of its usual range.

In the end, I think sea serpent sightings probably comprise a healthy mix of misidentification, hoaxes, illusion, as well as probably more than one type of unknown animal. In the instances where it is an unknown species, they could be members of a very rare species, which when combined with the unexplored vastness of the oceans, would explain their ability to evade detection and more numerous accounts.

One thing that has always facinated me about some eye witness accounts of the Loch Ness Monster, is the various ‘on land’ sightings. Some have described a creature that moves in a waddling fashion in a very similar way that a seal or an otter does when they are on land. Could Nessie be a long necked seal? If it’s not a plesiosaur, which is unlikely, then it’s more likely to be mammalian. The only two mammals that bare any resemblance to eye witness accounts are seals and otters. So who knows maybe a long necked seal or a dobhar-chu the giant otter.

Very interesting article. Well done to Darren Naish for digging up this new information.

It looks like there is a contest for who can make the longest post…haha.

“The head and neck of this species are exactly like those of an otter.”.

When I read that, I was very confused! it sounds like the author was writing about one species, and then immediately forgot was he was doing and began writing about another species! I don’t know what to think of this. The drawings don’t seem anatomically (the tails I noticed especially. Perhaps he is merely a poor artist, in which case, I CERTAINLY forgive him!) or proportionately accurate, either.

As expressed by previous commenters, this is an extremely interesting article. I find the notion of a “long-necked pinniped” to be compelling and refreshing in the face of the usual aquatic dinosaur/reptile theories. This is exactly the sort of research that makes cryptomundo such a great asset to the cryptozooligical community.

Lake/ocean cryptids are among my favorite, and I look forward to future postings.

Actually, Megophias megophias looks just like what I believe the Loch Ness Monster looks like! I believe that the Loch Ness Monster, if it isn’t a plesiosaur, is most likely to be a new species of long-necked, long-tailed pinniped, just like that drawing, above. Maybe it evolved to look like a plesiosaur, because of convergent evolution. And maybe it also evolved echolocation. In my opinion, echolocation would almost be a necessity, if an animal were to find its prey, in the black, murky, and peat-stained waters, of the loch. And, so, Megophias megophias appears to me to be the perfect candidate, for the Loch Ness Monster.

An oldie but goodie brought to your 2013 attention because of the current discussion of the thin theory of “giant salamanders” in Loch Ness.

You know what trips me out? Is that folks can believe in Nessie and not Bigfoot? It just is weird to know that people are all into Nessie and can NOT see a Bigfoot as relavant? Weird……

i did see these long sea otters in brazil? on a show…. they were pretty long but not like 10+ ft.

The other thing, if it needed to come up for air all the time, wouldn’t that in and of it self mean much more sightings?

my thinking, and this is just a normal person talking… is it could be an evolved whale of some sort…. like champlain, they found bones…. and they had echolocation… which would mean a dolphin/whale of some sort…. no?

this is all super fascinating…

If it were a pinneped it would be breaching the surface quit often to fill its lungs with air. Suggesting that the cryptids in the Loch/Champlain are pinnepeds is dubious since we would be seeing these creatures quite often coming up for air. Pinnepeds also give birth and raise their young on dry land so these creatures would have been observed multiple times. Pinnepeds also tend to be very curious creatures (I have had ones come right upside a boat while I am fishing) so I would think the sightings would be more numerous. My guess would be an aquatic reptile or eel….something with gills.

Additionally, if it were a pinniped, that was not a permanent resident of the loch, thus no rookeries, the only connection to the sea is River Ness.

The river is about 8 miles long and goes through the center of Inverness, a city of some 60,000 people. In Inverness, the river is about 60 meters wide. At one point near the Infirmary Bridge, the river is about 30 to 100 centimeters deep, though it does rise considerably after heavy rains. Fisherman can walk across the river here. There are also the handful of weirs throughout its length that lie just below the surface.

Grey seals obviously get up the river into the loch, they are seen there, the grey seal bulls usually maxing at 11 ft. If an unknown pinniped that is twice the size or more, can accomplish the same, and not be seen by the residents of Inverness, is another question perhaps.

I still would think a good candidate would be a creature that does not need to spend a lot of time at the surface, and a salamander species does fall into that category.

There are certain aspects of many descriptions that are quite common and if we start with these and work backwards, we should at least narrow down reptile/amphibian or mammal.

From what I recall some common traits are: horse-like head (sometimes with mane and/or “horns”), smooth body, moves up and down on the water as opposed to side to side, solid coloring (no striping, spots, mottling, etc.).

Is there anything in the fossil record that shows any long-necked pinnipeds or other sea mammals? What are the advantages of having long slender bodies, necks, and tails? If pinnipeds are indeed what’s living in places like Loch Ness, I think there would be a lot more land sightings of a few lying out on the shore, no?

I admit, I know virtually nothing about pinnipeds, so I’m going from a layman’s viewpoint.

That is a good point bobzilla, what having an elongated might be a disadvantage to a pinniped, their shorter bodies are good for retaining body heat in the cold water that they live in. Being longer would increase body heat loss I’d imagine, unless they were also more equally more massive to account for it.

I suggest that the best chance of solving this mystery lies not in tracking down the cryptid in the wild, but tracking down the specimen in the museum.

Museums, especially British ones, are famous for not throwing anything out. In fact, the older the specimen gets, the greater the chance it will be retained.

Somewhere, the type specimen is probably sitting in a dark storeroom or basement, covered in dust, awaiting discovery.

There are problems with both the “Giant Salamander” and “Long-necked Seal” explainations for Loch Ness sightings.

“Giant Salamander”

1. Most if not all aquatic salamanders live in shallow water evirons.

2. All aquatic salamanders lay an egg mass in shallow water which should have been seen and known to locals.

3. The many larva salamanders would stay in very shallow water to avoid predacious fish and eels and should have been seen and known to locals

4. Extant Giant Salamanders – Cryptobranchidae – can be caught and are often hooked by fishing lines. This would have hapened in Loch Ness by now and be know to locals.

5. 3-4 species of salamander…more properly newts, are found in Scotland and live at and around Loch Ness. They all go through an eft stage and spend time on land.

They are all known to locals and present no mystery.

“Long-necked Seals or Pinnipeds”

1. Old zoological misidentifications aside, no long-necked pinipeds have been found…alive or extinct.

2. All pinnipeds are air breathers and would be a common sight at the surface.

3. The great majority of pinnipeds are marine animals. Two species of fresh water pinnipeds exist but they are well known and present no mysteries to locals.

4. Pinnipeds have their young in rookeries and many live as groups for life.

5. Pinnipeds as a group are both social and gregarious and would be seen and well known to locals. There are occasional visiting seals in the Loch and they are known to locals…pinnipeds also make a wide range of loud vocalizations, well known to locals but unknown at Loch Ness.

These problems aside, either explantion is possible as opposed to being impossible but are highly unlikely, as the terms of their life-styles would make both options well known to the locals.

By the way…check out the skeletal image for a Sea Lion on Google. They do have a surprisingly long neck after removing the blubber layer. Perhaps the “long-necked”

specimen described in olden days was from a deceased and dissicated example. It would certainly appear very different in those days…

Pardon my correction; I meant dessicated not dissicated…my spelling dyslexia striking again.

I’ve always been a fan of the long necked pinniped. If Nature is good at anything and has proven anything, it’s that animals will evolve to fit a niche. The ocean offers rich examples of really odd critters that are very specialized and varying in size. Look at the whale populations in terms of size. It’s not a stretch of the imagination (or the neck) that a long necked seal of larger size would be possible.

The ocean is the one environment that allows for larger critters which are often only stinted in size by food, predators and population. As was pointed out, it could be that such critters have become extinct or are on their way there.

On the other hand, as I said up there somewhere, the number of sightings of sea serpents may indeed be misleading because of shipping lanes–most ships take the shortest point to destination or follow present shipping lanes and creatures are smart enough to figure out that the best way to avoid big objects moving through the water is to avoid those areas if travel is consistent.

Obviously over fishing could have an impact on larger creatures too.

Interesting that this subject popped up as I just saw an amazing photo online the other day of a leopard seal extending its neck to devour a penguin.

http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/technology/2013/01/leopard-seal-nabs-penguin-in-the-antarctic/

But a seal with a significantly longer neck? Hmm…Never say never with nature!