February 8, 2007

Ben Radford, managing editor of Skeptical Inquirer and resident skeptic of all things cryptozoological in nature, has given me permission to repost his article entitled Bigfoot at 50 here on Cryptomundo.

It is a lengthy article, so I have posted excerpts here. The article can read in its entirety at the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry website.

Evaluating a Half-Century of Bigfoot Evidence

The question of Bigfoot’s existence comes down to the claim that “Where there’s smoke there’s fire.” The evidence suggests that there are enough sources of error that there does not have to be a hidden creature lurking amid the unsubstantiated cases.

Benjamin Radford

Though sightings of the North American Bigfoot date back to the 1830s (Bord 1982), interest in Bigfoot grew rapidly during the second half of the twentieth century. This was spurred on by many magazine articles of the time, most seminally a December 1959 True magazine article describing the discovery of large, mysterious footprints the year before in Bluff Creek, California.

A half century later, the question of Bigfoot’s existence remains open. Bigfoot is still sought, the pursuit kept alive by a steady stream of sightings, occasional photos or footprint finds, and sporadic media coverage. But what evidence has been gathered over the course of fifty years? And what conclusions can we draw from that evidence?

Most Bigfoot investigators favor one theory of Bigfoot’s origin or existence and stake their reputations on it, sniping at others who don’t share their views. Many times, what one investigator sees as clear evidence of Bigfoot another will dismiss out of hand. In July 2000, curious tracks were found on the Lower Hoh Indian Reservation in Washington state. Bigfoot tracker Cliff Crook claimed that the footprints were “for sure a Bigfoot,” though Jeffrey Meldrum, an associate professor of biological sciences at Idaho State University (and member of the Bigfoot Field Research Organization, BFRO) decided that there was not enough evidence to pursue the matter (Big Disagreement Afoot 2000). A set of tracks found in Oregon’s Blue Mountains have also been the source of controversy within the community. Grover Krantz maintains that they constitute among the best evidence for Bigfoot, yet longtime researcher Rene Dahinden claimed that “any village idiot can see [they] are fake, one hundred percent fake” (Dennett 1994).

And while many Bigfoot researchers stand by the famous 16 mm Patterson film (showing a large manlike creature crossing a clearing) as genuine (including Dahinden, who shared the film’s copyright), others including Crook join skeptics in calling it a hoax. In 1999, Crook found what he claims is evidence in the film of a bell-shaped fastener on the hip of the alleged Bigfoot, evidence that he suggests may be holding the ape costume in place (Dahinden claimed the object is matted feces) (Hubbell 1999).

Regardless of which theories researchers subscribe to, the question of Bigfoot’s existence comes down to evidence- and there is plenty of it. Indeed, there are reams of documents about Bigfoot-filing cabinets overflowing with thousands of sighting reports, analyses, and theories. Photographs have been taken of everything from the alleged creature to odd tracks left in snow to twisted branches. Collections exist of dozens or hundreds of footprint casts from all over North America. There is indeed no shortage of evidence.

The important criterion, however, is not the quantity of the evidence, but the quality of it. Lots of poor quality evidence does not add up to strong evidence, just as many cups of weak coffee cannot be combined into a strong cup of coffee.

Bigfoot evidence can be broken down into four general types: eyewitness sightings, footprints, recordings, and somatic samples (hair, blood, etc.). Some researchers (notably Loren Coleman 1999) also place substantial emphasis on folklore and indigenous legends. The theories and controversies within each category are too complex and detailed to go into here. I present merely a brief overview and short discussion of each; anyone interested in the details is encouraged to look further.

1. Eyewitness Accounts

Eyewitness accounts and anecdotes comprise the bulk of Bigfoot evidence. This sort of evidence is also the weakest. Lawyers, judges, and psychologists are well aware that eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable. As Ben Roesch, editor of The Cryptozoological Review, noted in an article in Fortean Times, “Cryptozoology is based largely on anecdotal evidence… [W]hile physical phenomena can be tested and systematically evaluated by science, anecdotes cannot, as they are neither physical nor regulated in content or form. Because of this, anecdotes are not reproducible, and are thus untestable; since they cannot be tested, they are not falsifiable and are not part of the scientific process… Also, reports usually take place in uncontrolled settings and are made by untrained, varied observers. People are generally poor eyewitnesses, and can mistake known animals for supposed cryptids [unknown animals] or poorly recall details of their sighting… Simply put, eyewitness testimony is poor evidence” (Roesch 2001).

Bigfoot investigators acknowledge that lay eyewitnesses can be mistaken, but counter that expert testimony should be given much more weight. Consider Coleman’s (1999) passage reflecting on expert eyewitness testimony: “[E]ven those scientists who have seen the creatures with their own eyes have been reluctant to come to terms with their observations in a scientific manner.” As an example he gives the account of “mycologist Gary Samuels” and his brief sighting of a large primate in the forest of Guyana. The implication is that this exacting man of science accurately observed, recalled, and reported his experience. And he may have. But Samuels is a scientific expert on tiny fungi that grow on wood. His expertise is botany, not identifying large primates in poor conditions. Anyone, degreed or not, can be mistaken.

2. Footprints

Bigfoot tracks are the most recognizable evidence; of course, the animal’s very name came from the size of the footprints it leaves behind. Unlike sightings, they are physical evidence: something (known animal, Bigfoot, or man) left the tracks. The real question is what the tracks are evidence of. In many cases, the answer is clear: they are evidence of hoaxing.

Contrary to many Bigfoot enthusiasts’ claims, Bigfoot tracks are not particularly consistent and show a wide range of variation (Dennett 1996). Some tracks have toes that are aligned, others show splayed toes. Most alleged Bigfoot tracks have five toes, but some casts show creatures with two, three, four, or even six toes. Surely all these tracks can’t come from the same unknown creature, or even species of creatures.

3. Recordings

The Patterson Film

The most famous recording of an alleged Bigfoot is the short 16 mm film taken in 1967 by Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin. Shot in Bluff Creek, California, it shows a Bigfoot striding through a clearing. In many ways the veracity of the Patterson film is crucial, because the casts made from those tracks are as close to a gold standard as one finds in cryptozoology. Many in the Bigfoot community are adamant that the film is not-and, more important-cannot be a hoax. The question of whether the film is in fact a hoax or not is still open, but the claim that the film could not have been faked is demonstrably false.

Grover Krantz, for example, admits that the size of the creature in the film is well within human limits, but argues that the chest width is impossibly large to be human. “I can confidently state that no man of that stature is built that broadly,” he claims (Krantz 1992, 118). This assertion was examined by two anthropologists, David Daegling and Daniel Schmitt (1999), who cite anthropometric literature showing the “impossibly wide” chest is in fact within normal human variation. They also disprove claims that the Patterson creature walks in a manner impossible for a person to duplicate.

The film is suspect for a number of reasons. First, Patterson told people he was going out with the express purpose of capturing a Bigfoot on camera. In the intervening thirty-five years (and despite dramatic advances in technology and wide distribution of handheld camcorders), thousands of people have gone in search of Bigfoot and come back empty-handed (or with little but fuzzy photos). Second, a known Bigfoot track hoaxer claimed to have told Patterson exactly where to go to see the Bigfoot on that day (Dennett 1996). Third, Patterson made quite a profit from the film, including publicity for a book he had written on the subject and an organization he had started.

4. Somatic Samples

Hair and blood samples have been recovered from alleged Bigfoot encounters. As with all the other evidence, the results are remarkable for their inconclusiveness. When a definite conclusion has been reached, the samples have invariably turned out to have prosaic sources-“Bigfoot hair” turns out to be elk, bear, or cow hair, for example, or suspected “Bigfoot blood” is revealed to be transmission fluid. Even advances in genetic technology have proven fruitless. Contrary to popular belief, DNA cannot be derived from hair samples alone; the root (or some blood) must be available.

Hoaxes, the Gold Standard, and the Problem of Experts

Such hoaxes have permanently and irreparably contaminated Bigfoot research. Skeptics have long pointed this out, and many Bigfoot researchers freely admit that their field is rife with fraud. This highlights a basic problem underlying all Bigfoot research: the lack of a standard measure. For example, we know what a bear track looks like; if we find a track that we suspect was left by a bear, we can compare it to one we know was left by a bear. But there are no undisputed Bigfoot specimens by which to compare new evidence. New Bigfoot tracks that don’t look like older samples are generally not taken as proof that one (or both) sets are fakes, but instead that the new tracks are simply from a different Bigfoot, or from a different species or family. This unscientific lack of falsifiability plagues other areas of Bigfoot research as well.

Bigfoot print hoaxing is a time-honored cottage industry. Dozens of people have admitted making Bigfoot prints. One man, Rant Mullens, revealed in 1982 that he and friends had carved giant Bigfoot tracks and used them to fake footprints as far back as 1930 (Dennett 1996). In modern times it is easier to get Bigfoot tracks. With the advent of the World Wide Web and online auctions, anyone in the world can buy a cast of an alleged Bigfoot print and presumably make tracks that would very closely match tracks accepted by some as authentic.

What we have, then, are new tracks, hairs, and other evidence being compared to known hoaxed tracks, hairs, etc. as well as possibly hoaxed tracks, hairs, etc. With sparse hard evidence to go on and no good standard by which to judge new evidence, it is little wonder that the field is in disarray and has trouble proving its theories. In one case, Krantz claimed as one of the gold standards of Bigfoot tracks a print that “passed all my criteria, published and private, that distinguishes sasquatch tracks from human tracks and from fakes” (Krantz 1992). He further agreed that it had all the signs of a living foot, and that no human foot could have made the imprint. Michael R. Dennett, investigating for the Skeptical Inquirer, tracked down the anonymous construction worker who supplied the Bigfoot print. The man admitted faking the tracks himself to see if Krantz could really detect a fake (Dennett 1994).

Smoke and Fire

Bigfoot researchers readily admit that many sightings are misidentifications of normal animals, while others are downright hoaxes. Diane Stocking, a curator for the BFRO, concedes that about 70 percent of sightings turn out to be hoaxes or mistakes (Jasper 2000); Loren Coleman puts the figure even higher, at at least 80 percent (Klosterman 1999). The remaining sightings, that small portion of reports that can’t be explained away, intrigue researchers and keep the pursuit active. The issue is then essentially turned into the claim that “Where there’s smoke there’s fire.”

But is that really true? Does the dictum genuinely hold that, given the mountains of claims and evidence, there must be some validity to the claims? I propose not; the evidence suggests that there are enough sources of error (bad data, flawed methodological assumptions, mistaken identifications, poor memory recall, hoaxing, etc.) that there does not have to be (nor is likely to be) a hidden creature lurking amid the unsubstantiated cases.

The claim also has several inherent assumptions, including the notion that the unsolved claims (or sightings) are qualitatively different from the solved ones. But paranormal research and cryptozoology are littered with cases that were deemed irrefutable evidence of the paranormal, only to fall apart upon further investigation or hoaxer confessions. There will always be cases in which there simply is not enough evidence to prove something one way or the other. To use an analogy borrowed from investigator Joe Nickell, just because a small percentage of homicides remain unsolved doesn’t mean that we invoke a “homicide gremlin”-appearing out of thin air to take victims’ lives-to explain the unsolved crimes. It is not that such cases are unexplainable using known science, just that not enough (naturalistic) information is available to make a final determination.

A lack of information (or negative evidence) cannot be used as positive evidence for a claim. To do so is to engage in the logical fallacy of arguing from ignorance: We don’t know what left the tracks or what the witnesses saw, therefore it must have been Bigfoot. Many Bigfoot sightings report “something big, dark, and hairy.” But Bigfoot is not the only (alleged) creature that matches that vague description.

The Future for Bigfoot

Ultimately, the biggest problem with the argument for the existence of Bigfoot is that no bones or bodies have been discovered. This is really the 800-pound Bigfoot on the researchers’ backs, and no matter how they explain away the lack of other types of evidence, the simple fact remains that, unlike nearly every other serious “scientific” pursuit, they can’t point to a live or dead sample of what they’re studying. If the Bigfoot creatures across the United States are really out there, then each passing day should be one day closer to their discovery. The story we’re being asked to believe is that thousands of giant, hairy, mysterious creatures are constantly eluding capture and discovery and have for a century or more. At some point, a Bigfoot’s luck must run out: one out of the thousands must wander onto a freeway and get killed by a car, or get shot by a hunter, or die of natural causes and be discovered by a hiker. Each passing week and month and year and decade that go by without definite proof of the existence of Bigfoot make its existence less and less likely.

On the other hand, if Bigfoot is instead a self-perpetuating phenomenon with no genuine creature at its core, the stories, sightings, and legends will likely continue unabated for centuries. In this case the believers will have all the evidence they need to keep searching-some of it provided by hoaxers, others perhaps by honest mistakes, all liberally basted with wishful thinking. Either way it’s a fascinating topic. If Bigfoot exist, then the mystery will be solved; if they don’t exist, the mystery will endure. So far it has endured for at least half a century.

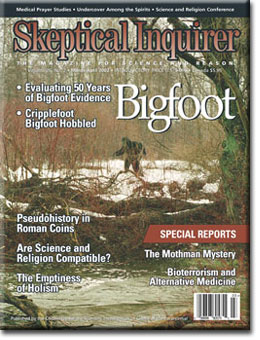

Cover image of Skeptical Inquirer

There are several other articles of cryptozoological interest in the same issue.

There is an article entitled Cripplefoot Hobbled by David J. Daegling.

Evidence for Bigfoot gains credibility when the possibility of human fabrication can be ruled out. The trackways of a crippled Sasquatch are said to provide such a compelling case, but examination of this claim suggests that hoaxing the footprints may have been a fairly manageable endeavor.

There is also the ‘Mothman’ Solved! article by Joe Nickell.

This may be more giant owl talk by Mr. Nickell.

The issue is available to order at Committee for Skeptical Inquiry website. Click on the cover image aboe to go to the website and purchase your very own copy.

About Craig Woolheater

Co-founder of Cryptomundo in 2005.

I have appeared in or contributed to the following TV programs, documentaries and films:

OLN's Mysterious Encounters: "Caddo Critter", Southern Fried Bigfoot, Travel Channel's Weird Travels: "Bigfoot", History Channel's MonsterQuest: "Swamp Stalker", The Wild Man of the Navidad, Destination America's Monsters and Mysteries in America: Texas Terror - Lake Worth Monster, Animal Planet's Finding Bigfoot: Return to Boggy Creek and Beast of the Bayou.

Filed under Artifacts, Bigfoot, Bigfoot Report, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Evidence, Eyewitness Accounts, Folklore, Forensic Science, Hoaxes, Mothman, Sasquatch