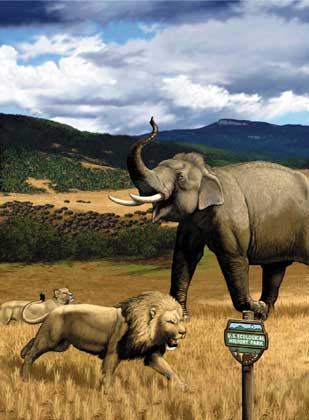

Bring Back The Mammoth?

Posted by: Loren Coleman on November 26th, 2008

DNA scientists have sequenced 70% of the mammoth’s genome. Photo: Stephen Schuster

It sounds like we are getting closer to cloning a mammoth.

Do you think the mammoth should be cloned and brought back to life?

“I think it’s impossible basically,” said Dr. Austin, deputy director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA. “And even if you did bring back mammoths, there’s nowhere … they could live.”

Apparently, Austin is badly out-of-the-loop, regarding the rather detailed talk of creating just such habitats for mammoths and more.

Should Paleo-Parks full of Pleistocene animals, with some cloned animals, exist?

Should some be retro-recovered through breeding, and some attractive Pleistocene survivors, depending on the location, species like musk oxen, pronghorns, wisents, and saigas, be brought together?

Should such parks be opened as active conservation reservations, for tourists and scientists?

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Ann Unknown- I can’t argue with that! We would most certainly be the biggest problem. We HAVE been the biggest problem. I think you are pretty spot on when you say that we are going to have to re-wild ourselves before any project like this could stand a chance.

This a well thought out debate here and I appreciate the civility. The incidental re-wilding of the horse 500 years ago brought about significant changes, namely in terms of bison and human ecology. Indians of the plains were essentially in a predator/prey relationship with the bison. Estimates of bison numbers range from 20 to 60 million. That is a very wide range. Prior to the horse, bison were stalked on foot. Suddenly, a new vehicle arrives and now the bison can be hunted very effectively. Now a band of 40 people grows to 100 due to the increased food supply. Consequently, the horse population grows as well-and eating the same food as the bison but at a 25% greater rate (horse Animal unit/month=1.25). You can see the feedback loop occurring here, sort of like cars competing for corn with the biofuels debacle. Despite the horse being a native species in North America at one time, it was part of the ecology when humans were not. This is ecology in a nutshell because each component depends upon all the other components. Putting together a former ecosystem on a scale of the Pleistocene Re-wilding proposal is an impossible task due to the infinite number of variables that are available.

Thanks for that input there, Ann Unknown. As far as the turtles being a far cry from a reintroduced mammoth, perhaps you’re right mystery man (I fully appreciate and recognize your insight on this), but we could easily test it out using Asian Elephants for which these is already a need as zoos and circuses begin to “retire” them. As for the horse introduction, the problem from the perspective of their overgrazing and competition was that we didn’t also re-introduce african lions and cheetahs whose ancestors in North America’s pleistocene landscape were no doubt a balancing factor.

I do appreciate mystery man’s careful and balanced perspective and don’t advocate just “rushing in” without a plan, but I swear the paralysis of analysis when it comes to this kind of strategy, coming surprisingly from the “environmental community” who for reasons that escape me are somehow worried that the character of the west will be harmed by it…really, the character of the western range is a degraded impoverished feed lot in far too many places with collapsed water tables and seas of uncontrolled and unwated (uneconomical) species. ..oh, and a touch of instinctive anxiety about children being eaten by cheetahs or lions thrown in for flavor despite the statistican near impossibilty of it happening.

Anyhow, I’ve enjoyed this discussion immensely. Here’s to more of it. cheers.

I believe the field of genetics is the future of Cryptozoology.

Eventually even the diehards will allow logic to creep into their bigfoot hopes and will need something to fill the void.

There will be rogue(and legitimate) individuals that create new life forms in much the same way people currently create computer programs AND viruses.

Soooooo……eventually there will be Mammoths(that actually used to exist) and others will have their ‘bigfoot’.

Re-wilding large animals will probably come down to semantics. The simple idea of having large, dangerous animals will never fly. Look at the reaction of the public with the introduction of native 120 lb gray wolves that rarely interact with humans. A 400lb lion just isn’t gonna go over well. However, elephants may be possible if it is pitched right. Shrub invasion into grasslands is a problem throughout the West, and elephants or rhinos are well suited to deal with this problem. If these large tree and shrub eaters could be used as a restoration tool, then it may stand a chance. Using these animals to perform a specific ecosystem function, such as woody plant removal, is a valid and very pragmatic use for re-wilding.

As far as Bolson tortoises are concerned, I don’t think that the re-introduction of them into their former range has done a great deal to modify the habitat to any great degree, after all there are only 25 of them that roam in a 17 acre enclosed space. The low metabolism, energy requirement and home range of a tortoise (the largest one weighing about 30lbs), and which spends 90% of it’s time underground, pales in comparison to even one cow when it comes to modifying a landscape. One aspect of Bolson tortoise restoration that is rarely discussed is the fact that it’s occurrence in the Southwest was prior to the Holocene. During the Pleistocene much of the former range of the tortoise was pinyon, juniper grassland and was not Chihuahuan Desert as it is now. The same goes for the Desert tortoise which has only existed in the desert for less than 0.1% of 1% of it’s evolutionary history. Being ectotherms, tortoise distribution is shaped by climate more than any other factor, specifically critical minimum temperatures that penetrate deep enough into burrows for extended periods of time. The climate of Bolson de Mapimi (the current wild range of the Bolson), is very different than the re-introduction site near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. To deem the Bolson tortoise re-wilding a success after only two years in the cold northern Chihuahuan Desert is like “W” declaring “Mission Accomplished” a few months after invading Iraq. Will a self sustaining population of tortoises be able to persist in a climate that is much colder than it’s current limited range? The premise of the Bolson’s re-wilding was that it was a victim of human overkill 11,000 years ago. However, climate change should not be ruled out, for it was very real and altered conditions in that part of the world dramatically. I feel as though the Bolson tortoise, being a living relict and survivor from the Pleistocene, may hold some of the clues to the ongoing climate change versus overkill debate.

Dogu4- Thanks, I have enjoyed this discussion very much too. It is very nice to be able to come together here with other well informed, thoughtful people with the same interests and discuss these things. Your input is much appreciated.

Flavomarginatus- I don’t know if you read all my comments above, but you seem to have the same concerns and a similar way of thinking as me. Thank you for your input. Just to add some thoughts to what you already said.

Yeah, the experiments with the Bolson tortoise are pretty small scale at this point in time. I tend to think this is how any such reintroduction effort should start, but indeed it won’t necessarily give us the full picture. Even if things seem Ok under the current conditions, some of the proposed animals have huge ranges, and with small scale experiments it might be hard to gage just how their movements and interactions with the larger environment will effect the overall plan and ecology.

There is also the relatively small number of test animals. I’m not so sure we can make any predictions on the success of the program from studying such a limited test population.

It is very hard to try and create a mini ecology and emulate every single subtlety. Like we have both mentioned here, ecology is a very complex thing with many variables. The composition of plant and animal assemblages in the habitat as a whole also can’t be fully taken into account with these small scale tests, nor can problems that may arise over long stretches of time. When the animals are released into the wild, there are bound to be unforeseen effects. It is an interesting program, but it might be a bit premature to call anything a success until more time has passed and wide range studies are done.

Another thing is that even if the tortoise currently interacts well with the ecology of the area they are currently in, I’m not sure that it necessarily means they are going to interact well with all of the animals from a range of trophic levels that are being considered for reintroduction. Some of these species have had their ancestors absent from the tortoise’s habitat for thousands of years and I’ve gone into the inherit problems of trying to use proxy species to fill in the blanks.

Even so, as I explained before, using extant species reintroduced into their historical range (like the tortoise) isn’t foolproof, but likely less problematic than using clones, descendants from long extinct species, or proxy species. I’m curious to see what further studies will turn up on the overall ecological effects of animals such as the Bolson tortoise, or other indigenous Pleistocene survivors like the puma and others being gradually returned to their previous geological ranges.

I am hopeful for some such reintroductions. Some reintroduction efforts have been successful, and they can be often be a sound conservation plan, but they all have to be thought out, especially ones on the scale of the proposed Pleistocene re-wilding. I’d say I agree with you that rather than trying to recreate a whole ecosystem, we can perhaps use animals that fulfill a particular ecological need or fill a long absent niche, for example the Yellowstone wolves mentioned earlier.

Anyway, this has been a great discussion from all sides. Many things to think about and consider, presented in a civil, respectful way. This is one of the reasons I love this site.

Actually, we already have a surviving check on the horses – the puma. (Incidentally, two years ago, a single puma took all 8 foals, produced by my neighbor’s Quarter Horse brood band, in one week.) I think the problem would more likely be foal survival than overpopulation, if we rethink predator control, as it is now practiced. And I doubt that most finely bred horses could fit the rewilding bill. My suggestion would be the old time Spanish mustangs , with 500-years of adaptation, just on this continent alone. (Mustangs with 500 years of adaptation, are far more rare, than most people would believe. I am told that there only as few as 4 herds. And even those are under the constant threat of being compromised by modern breed releases. Most BLM herds are composed of unwanted first, or second, generation abandoned livestock; the ugly equivalent of dumping out pets, when they outlive their appeal, IMHO. 🙁 )

As for the trees, shrubs, and the resulting falling water table: I believe the continent’s missing equines were as much a control on this, as was the mammoth. (Just ask any grandparent, who’s grandchild’s pony was introduced to their impeccably landscaped back yard – my own personal experience!)

And then, there are areas where even elephants/mammoths would have problems (the ecosystem changes since their extinction, mysteryman spoke of?). Case in point: the salt ceder invasives on the Gila River, in Arizona. Recently, a control program was implemented employing domestic goats. One of the major problems, as I understand it, was the intensive manpower necessary to “herd” the goats, in order to avoid salt toxicity. Equines, in fact, need salt, and are immune to this hazard. From what I have read, in some parts of Siberia this same plant species constitutes the greater part of their winter forage. Instinctively adjusting their water intake to compensate for the high salt levels, they require no human management. They could at least be of some value, reclaiming an area, preceding elephant/mammoth reintroduction.

Now flavomarginatus, I understand from my Texan friends, that they find me, a hole lot easier on the eyes, than ol’ Dubya. 😉

But I still think that 25 tortoises on 17 acres, constitutes a HUGE success – compared to 0 tortoises, on 0 acres, just a few short years ago. Guess I am regarding it as being relative to how turtle slow those tortoises reproduce.

Yes, a highly satisfying discussion. 😀

Mystery Man- Thanks for the feedback. The Pleistocene Re-Wilding gang, more than anything, have inspired a lot of discussion about ecology, policy, endangered species, exotic species, but not necessarily in that order. In fact, the weakest aspect of the proposal has been concerning the on the ground herbivory aspects, i.e. range management. Even native herbivore restoration, like bison, can be fraught with problems such as overgrazing. What many fail to take into account is the spatial and temporal aspect of herbivore movements. For example, the historic range of bison ranges from the Northwest Territories of Canada to southern Coahuila and possibly Zacatecas. Quite often the lines on maps empower people to assume that it is feasible to place bison on one piece of land for an very extended period of time, when in actuality the movements of these great herds followed the flush of green following good rainfall or fire. Therefore, there were periods when no grazers were present on a large tracts of land for a long time. I guess we need a whole continent to really do this thing right!

Flavomarginatus- Yes, that’s pretty much spot on. I’ve mentioned here earlier the problems that can be inherit even in reintroducing animals to their historical ranges. Herbivores especially can alter the dynamics of plant life in an area, and their movements are exactly like you said, wide ranging and difficult to predict. Also, overgrazing can have devastating effects on a grassland ecosystem. Just like I mentioned earlier, I think we really do need an adequately large area (maybe not a WHOLE continent 🙂 ) to get any sort of real sense of how things are likely to work out. There have been successful herbivore reintroduction projects, equids in particular have had some nice successes in some areas, so any such plan is not doomed to disaster. But it does need a lot of study and consideration.

To me, even even indigenous ones returned to native geological ranges are absolutely going to pose potential problems. However, I’m more worried about importing exotic herbivore species, or species from any trophic level for that matter, as proxies. That is something that should be approached with caution and I am not comfortable with the assumptions some have made in such debates that this could go smoothly in any way.

The whole Pleistocene renewal debate is fascinating to me because it hits on some of my main areas of professional interest, which are ecology and the effects of introduced species on Native ecosystems (for all intents and purposes the same essential situation that could cause problems with these re-wilding plans). The debate is opening up all kinds of great discussions on the areas you mention, and I would encourage this to continue before any plan is pushed forward.

Ann Unknown, Flavomarginatus- I tend to agree with what Ann Unknown said that perhaps starting small is better than nothing at all. There are actually many successful cases where such reintroductions were started on a small scale and gradually expanded.

If I remember correctly, the Przewalski’s horse of China and Mongolia was one such case. In the late 1960s, it was considered extinct in the wild and by 1979 there were fewer than 400 surviving individuals in captivity. They were reintroduced in two limited areas and one population increased by around 50%, therefore encouraging further reintroduction in their historic range based on the positive overall results of the first attempts. While it may be too early to tell the long term effects, it seems that the program is a success so far. So here we have a large grazer that was reintroduced to its historic habitat without major problems.

Anyway, successes are certainly not guaranteed, and one could argue that these experiments use time, money, and effort that may be better spent elsewhere on other conservation measures.

Going back to indigenous versus exotic grazers, I tent to feel that cases involving indigenous extant animals, like the Przewalski’s horse in Asia, or expanding the range of the bison in North America, tend to hold more of a chance of working out in general. Of course these large herbivores can possibly overgraze, and differences in species compositions since the animal’s absence have to be considered, but I am more optimistic with these species than with using exotic grazers. Exotic feral horses, for example, have drastically altered plant ecology in marsh lands and grasslands in some areas where they were introduced, which can cause a ripple effect throughout the ecology. There’s not always a sure fire way to tell what they will choose to eat either, and they could decide that they like rare plants or plants that another species prefers, putting them in direct competition and resulting in culmanitive overgrazing.

In order for large herbivores to have a chance of successfully being reintroduced, there has to be a healthy overall ecosystem put in place. There need to be predators. This is likely where public opinion is going to hold sway, as conservation efforts tend to reach more opposition with reintroductions of predators. No matter how remote the proposed area, there is always a chance of escape, and many people are not comfortable with the idea of having wolves or pumas released. I can’t imagine that any such plan will not meet some opposition, no matter how unfounded those fears may be. I can imagine that species commonly seen as somewhat more benign, such as elephants or even camels may have similar effect of public perception.

So this comes around to what Flavomarginatus touched on concerning policy and public opinion. In order to make sure that herbivore species of a Pleistocene re-wilding are operating at a healthy level and not negatively impacting the plant ecology, all of the pieces of the bigger picture have to be in place, such as predators. But to do this, the project will need public support.

So we have an interesting mix of ecological concerns, logistics, economics, biology, policy, and public opinion here with trying to recreate Pleistocene ecological models.