November 5, 2007

The Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts held their Twenty-First Annual Conference in Portland, Maine, on November 1-4, 2007. It was called SLSA ’07: CODE. The conference was intellectually stimulating and extremely academic.

One paper read told of ground-breaking implications for cryptozoology, as the term “cryptid” explodes beyond the boundaries of our field. But more of that later.

Professor Susan McHugh, from her university website.

I was humbled to be an invited guest of one of the conference organizers, the University of New England’s Susan McHugh, the author of Dog (Reaktion, 2004).

McHugh is someone well aware of cryptozoology and its place in the pursuits of a few of the people at the SLSA conference. Little did I know these borderlands were being acknowledged and academically realized, but I soon discovered much, based on the talks I attended.

The diversity of the people there and of the subjects covered was startling. I felt right at home.

The topics under discussion projected fundamental areas of inquiry that appealed to the attendees on many levels. I learned the jargon of the conference quickly, so I would not be such a stranger in a strange land. Their introductory material gives a hint of what I’m talking about:

Biological and algorithmic, protector of secrets and porthole to mysteries, universal and singular, code is an invitation to thought. Code can be “wet” (genetic, organic, human), “dry” (digital, mathematical, logical), something in-between, neither, or both (linguistic, symbolic, religious, moral, legal). Code is the meeting ground of strange bedfellows, the cipherer and decipherer, the domain of law and its subversion, communication and privacy. Code is about patterns, sequences, systems, translations, substitutions. It can bind, trick, and free. Modern technologies are affording us more and more keys to unlock nature’s code and more opportunities to manipulate it.SLSA ’07: CODE Program

SLSA ’07 featured two plenary sessions and twelve regular sessions with up to seven concurrent panels. I went to three different sessions and listened to ten papers. It felt like that enjoyable part of college, where as a student I picked all the electives I wanted and went to only the classes I wished to attend.

Thursday afternoon, for example, I went to listen to a panel of three papers so I could specifically hear Buena Vista University professor Jon Paulson’s presentation, “Cryptids, Cyborgs and the Malleability of Being.”

The Great Chain of Being, from Charles Bonnet, Œuvres d’histoire naturelle et de philosophie, 1779-83.

Here is Paulson’s abstract:

Using Jeremy Bentham’s notion of fictions and Kenneth Burke’s concepts of hierarchical mystery and perfection, this paper examines how the medieval concept of the Great Chain of Being, albeit in a new form, maintains a political structure used by humans to maintain dominance over animals. Specifically, the concepts of both Cyborgs and Cryptids are used to explore how science and folklore politicize the nature of Being in the contemporary world.

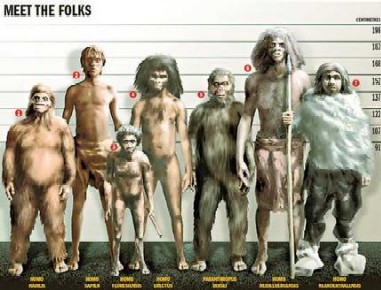

Viewed as discourse, the Great Chain of Being seeks to perfect the world. However, the epistemic rhetoric of the model does not always neatly match the ontological experience of the world. Therefore, humans have created beings, both “real” and fictional, to try to close the gaps, or provide “missing links.” Cryptids, especially quasi-humans or quasi-primates such as wodewoses or yeti, demonstrate how humans have used fictions to fill in the perceived gap between humans and animals. Cyborgs, conversely, use technology to either “complete” a human (through surgery or prosthesis) or elevate a “lower” animal to a more human like status (through genetics, as in the Onco-mouse; or through computers, as in some ape language studies). The paper concludes by addressing the political implications of such a linear and hierarchical model being used theoretically and ethically to articulate the nature of Being for human and non-human animals. – Jon Paulson

Professor Jon Paulson, from his university website.

Paulson’s was an interesting paper, and he talked of the new void that cryptids fill in the Great Chain of Being, in his view. I spoke up after his paper was read, in mild disagreement that he’d left out the “imperfection” in his thesis that the discovery of cryptids like the giant squid, mountain gorilla, okapi, or even the recent dwarf manatee disrupts the status of these cryptids only existing as never-found, wispy maybe creatures. He agreed.

The next day I had lunch with Paulson, whom I found to be down-to-earth and an enjoyable guy. We had a good wide-ranging discussion of Bigfoot, cryptids, and his novel work with interspecies communication with bonobos. Paulson shared with me a gem from his field, which I hope to write about someday, as soon as the Iowa-based developments are publicly released.

On Friday, I attended the SLSA conference to listen to the paper that got my most attention from the abstracts, the one by the University of Houston-Downtown’s Stephanie S. Turner.

Turner’s paper was given in the midst of the panel called “Cross-Breeding Freaks.” Her presentation was of special interest, needless to say, as it carried a simple and direct title, “Code-breaking Cryptids.”

Her abstract overviews where she went during her talk:

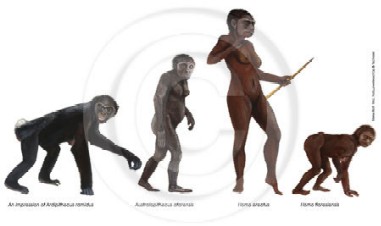

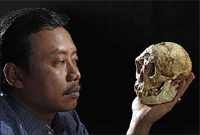

The broad category of hypothetically extant animals known as “cryptids” resists organization. In addition to mythic creatures like the Australian bunyip and the Tibetan Yeti, cryptids include species thought to be extinct though still ardently searched for, like the Tasmanian tiger and the North American ivory-billed woodpecker; and newly discovered, taxonomically uncertain fauna like the dwarf hominid designated “Flores Man” recently excavated in Indonesia. Despite the currency of the term predominantly among cryptozoologists, “cryptid” is also used in mainstream sciences to describe feral animals, animals outside their usual habitat, mutants, and hybrids.

This slippage of the term across fields of inquiry suggests the code-breaking characteristics of cryptids: cryptids defy taxonomies and disrupt evolutionary explanations, showing up everywhere. Whether monstrous, lost, found, gone wild, stray, or transformed, they elude human government of the natural world, reminding us of our limited power and knowledge. In this way, code-breaking cryptids also function as recognizable outposts of viability. Typified by an iconic association with place, cryptids are thus mappable, their expression in a variety of forms irresistible—though they remain, paradoxically, inscrutable.

Following Stephen Jay Gould’s advice that “we can best understand a natural object or category by probing to and beyond its limits of actual occurrence,” in this presentation I examine several instances of cryptid code-breaking in narrative and visual modes: science journalism’s speculative revisions of human evolution triggered by the Flores Man discovery; Tasmanian folklorist Col Bailey’s photographic presentation of the extinct thylacine; and artist Alexis Rockman’s refiguration of taxonomies to include all manner of cryptids. – Stephanie S. Turner

Turner’s brilliant and excellent paper captured sharply the expanding nature of the use of the word “cryptid” across many cultural and codification parameters. Her exploration of the uses of “cryptid” was a journey through the literary hybrid rainforest that mixes the sciences and humanities, zooanthropology and art, and establishment views and rogue taxidermy.

In her paper, Turner cites folklorist Peter Dendle, who has written that cryptozoology is “more important now than ever” (Turner, page 10 of her paper) because of a felt need to “repopulate liminal space with [the] potentially undiscovered creatures that have resisted human devasation,” (from Dendle, Peter, “Cryptozoology in the Medieval and Modern Worlds,” Folklore 117, August 2006, specifically page 198).

Professor Turner’s notion is that “we need to engage more ways of knowing that are ulterior from and exterior to establishment science in the everyday problem-solving mode.” (Turner, p. 10).

With her permission, I will quote fully Turner’s concluding paragraph, which nicely sums up the vast horizons she foresees for the use of the living word under discussion here:

It is time, then, for the term “cryptid” to take on a broader meaning. Referencing as it does the uncanniness of human-animal encounters, that familiar otherness about nonhuman species that so unnerves yet intrigues us, the term serves as a useful conceptualization in cultural studies of species – which is, finally, the ultimate work of natural science, cryptozoology, anthropology, and any creative representation of non-human others. – Stephanie S. Turner, “Code-breaking Cryptids,” SLSA ’07: CODE, November 2, 2007.

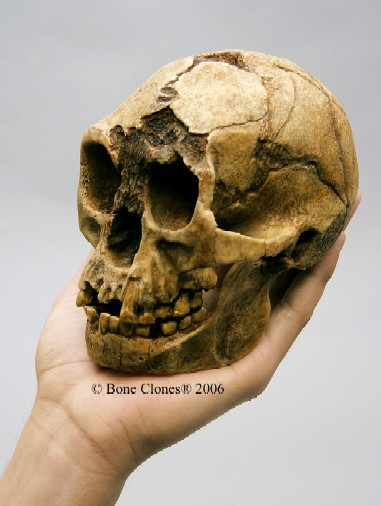

On Sunday, November 4, 2007, professors McHugh and Turner toured my International Cryptozoology Museum. I was delighted to show them various unique items that overlapped into their interest areas, such as the first BoneClones museum-quality replica of the Flores woman skull, the Adam Davies cast of an Orang Pendek track, Dick Klyver’s bronze of the Teh-lma, and the bust of the austropithecine Lucy.

Catching their eye, as well, were fake taxidermy items, such as the fur-bearing trout, Feejee Mermaid, and Jenny Haniver.

Professor Turner now has for her research library my very last extra copy of Cryptozoology Out of Time Place Scale by Mark Bessire and Raechell Smith, the companion volume to the Bates College exhibition. Both also took away autographed copies of Cryptozoology A to Z from our visit.

I’m happy the SLSA visited Portland, and I was able to listen to some of the significant (to me) talks. The presentations I attended demonstrated that much can be learned from how cryptozoology is now being viewed outside our field and how it fits into the scheme of things now and to come.

Professor Stephanie S. Turner’s final published paper is one that cryptozoologists, and those interested in cryptozoology will definitely want to read.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Filed under Abominable Snowman, Artifacts, Bigfoot, Books, Breaking News, Conferences, Conspiracies, Cryptid Canids, Cryptomundo Exclusive, Cryptotourism, CryptoZoo News, Cryptozoologists, Cryptozoology, Extinct, Folklore, Forensic Science, Fossil Finds, Hoaxes, Homo floresiensis, Media Appearances, Men in Cryptozoology, Museums, Out of Place, Photos, Pop Culture, Public Forum, Reviews, Sasquatch, Thylacine, Women in Cryptozoology, Yeti