Tajik Yetis

Posted by: Loren Coleman on July 25th, 2010

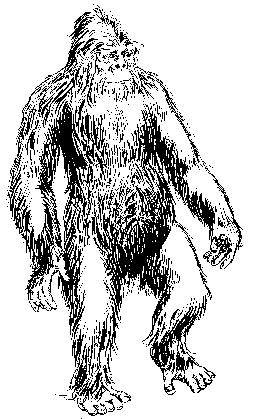

Yeti art from Guide Des Animaux Cachés by Philippe Coudray.

Has a new country opened up for future Yeti expeditions?

Have you ever heard of Tajikistan?

“Following independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Tajikistan developed a new flag on Nov. 24, 1992. The green stripe is for agriculture, while red is for sovereignty. White is for the main crop–cotton. The central crown contains seven stars representing unity among workers, peasants, intellectuals, and other social classes.” Source.

It apparently is a land of the Yetis.

In Standing Point Magazine (July/August 2010), Ben Judah travels to “Tajikistan: In Search of the Yeti.” In part, he writes:

In a valley of penury, 65km from Dushanbe, they have started to see monsters. Romit Valley curves towards the mountains, sprinkled with medieval hamlets and third-world townlets. They are not frightened of the mujahideen but they are scared of the Yeti.

The Tajik intellectual Mullojanov takes this matter seriously. “I have heard such rumours of a Yeti, or Khull as it is known in Farsi, since my childhood. There were even several expeditions dispatched by the Soviets to find it, including ones organised by the Soviet Academy of Sciences. There were many sighting by locals and Soviet soldiers, but never any actual proof. It is theoretically possible it could be a relic population of Neanderthals, outcasts, hermits or some unknown mountain monkey. Sightings of the Yeti rose dramatically during the civil war. People started shooting at him.”

I went in search of the Yeti in rustic Tajikistan.

My guide Surob dreams of supermarkets, wishing for a future where he is the head of a Tajik-style Tesco. He knows Romit Valley like the back of his hand. We begin the hunt after lunch. As Surob accelerates out of Dushanbe in a “borrowed” car, he breaks into a rapid running commentary in imperfect English made up of American slang off the TV: “Now we go eastside, find the mens who will tell us about Yeti.”

A devout Muslim who has studied in Iran, Surob is proud of his country and speaks fluent, eloquent Arabic. He rattles on. “Tajikistan we call small paradise, Tajikistan like the virgin girl, almost all is mountain, many supreme flowers, the herbals…” He has a beautifully maintained black moustache, a goatee he thinks is cool and boyish good looks. “Farsi man most beautiful in world, like me.”

Surob will stake his honour on the Yeti’s existence. “I saw his footprints, bigger than the man’s, in snow.”

The road slides upwards from Dushanbe and starts to disintegrate. Surob gestures towards a sad-looking town to our right. “That’s town where I was born, after collapse Soviet Union, people started banging, stealing, breaking everything, proving they themselves are the Yetis.” He bristles when I suggest the Yeti may be a peasant mirage. “They swear on the Koran. Why should they lie? They know nothing, they have nothing, they swear by Allah they have seen it.” I back down.

We pull up at a shack for a pit stop. This is where the valley begins. I am peckish. Soviet-style sweets are displayed in plastic bags. “What’s the best one?” I ask in Russian. The proprietor dashes to a side room and brings me a Snickers bar. My guide wants to hurry, but an old man with an unwashed beard and one strikingly yellow tooth asks for a ride up towards his village. Surob asks him if he is from here. “He from here. Now I will gather the informations.”

The peasant knows about the Yeti. “Ten years ago, I saw him. I was climbing a hill to gather firewood and I saw somebody. I go hey, hey, but then he started running towards me. It was the Yeti, covered in black wool, with breasts like the woman’s…”

I ask him to swear on the Koran that he saw the Yeti. Raising his hand to heaven the old man insists and gives me his Islamic word. “I don’t know about other people, but I saw it. It was shouting with anger, rarghh, I was shouting with fear, eeee, and I run.” The countryside changes dramatically as we talk. The road has become a dirt track. The car is swerving and sidling as it climbs up the barren gullies. The old man insists he saw the Yeti. Everyone knows somebody who has in the nearby villages. “When I got back to the village, my father started reading the Koran to me, as protection.”

Nature is starting to blossom in rich abundance. Cherry blossom hangs off the crags. Shoots of wild onions sprout out of the dark earth. “Look,” says Surob. “Look at the herbals, the Yeti is eating the herbals, this is why he lives here.” Coloured tips of wild flowers, blues, reds, purples, grow among the jagged browns, reds and greys of the mountains. Another curve. A stark, barren river valley. “Hey, they saw him too.” Surob stops the car and gives traditional greetings to two middle-aged men driving the traditional clapped-out Lada.

“Yeah, I had fight with him,” says the hunter. “He has wool, black wool, and these breasts…” And he wolf-whistles. His companion, a chubby man in a sizeable skullcap, butts in. “Oh yes, I was up in the glade, and he attacked my donkey. It was very frightening. He looked like a wild man — or a clever monkey.” The sightings occur in the same places. Regularly.

We continue to drive upwards. Snow-capped peaks shine luminously under the beating spring sun. “This is Yeti village.” The car enters the impoverished village of Tavish. Sheep block the small bridge. They are not cloud-white and fluffy like our sheep. They are yellow, ragged and small. Groups of little boys flit here and there. The car kicks up dust and swerves violently as we pass over a stone. The mud-brick houses have wooden roofs; electricity arrived three years ago and works for only an hour or two a night. The homes remind me of Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters. I am inside a rustic genre painting. A stench hangs in the air.

We get out and turn to the first man we see. Khikmotill’s clothes are dyed red from animal slaughter. He wears a thin, sky-blue smock and traditional striped cloth trousers. Tanned, eyes faintly Asiatic, he shakes my hand. “My cousin saw the Yeti, four days ago, with his younger brother out picking wild onions. He couldn’t speak for days he was so scared.” This unnerves me. Khikmotill summons him. Assodin is 15, has a small nose, spectacular mono-brow and a jet-black crew-cut. He wears a Reebok T-shirt of dubious quality.

Surob translates for me. “He says he saw Yeti three kilometres into mountain, and he hear whistling, and he says he saw Yeti climb over the stones, that Yeti looks like clever monkey, that he do whatever you do — you scratch your nose, he scratch his nose. Yeti then comes, he runs away.” I ask the boy to draw the Yeti. It is an unexpectedly childish drawing, a box with stick arms. Surob is surprised. “He saw Yeti where I saw Yeti footprint in snow.” I ask them to take me up there.

We begin to trudge up the isolated glade. Rock precipices rise smoothly skyward. A burning white mountain stands at the faraway head of the narrow valley. “This spot is where hunters saw him. We see footprints in sand of him, in the spring, then in the snow,” Khikmotill explains. Both he and his cousin seem nervous as we press forward. Further up, uninhabited plateaus stretch for miles on either side of the valley. The villagers claim they have discovered ancient stone circles there. There is tension in the group. The boy jumps from rock to rock, with the agility of a goat, over a gushing stream fuelled by melt-water.

“Come on city boy.”

I grab branches, bend trees to scramble over the water. Woods give way to brown thickets. There are stings and cuts on my hand. We continue upwards. Out of breath after two kilometres, I question Khikmotill and the boy. “It could be wild man, but it looks like monkey. We don’t know, we see it.” The boy swears on the Koran he is not lying. When I suggest oaths are not always foolproof, Surob erupts.

“This is so important for Tajik people. If you swear on Koran and it’s lie, even if your house is burning, nobody ever believe, ever believe word you say, ever, ever again.”

He points to where the Yeti climbed over the rocks. Further up, we can see a small, almost inaccessible cave.

“His whistling chills to the bone.”

To my disappointment, there is no Yeti to be seen. The villagers point to a small waterfall where the Yeti has been seen washing. They seem relieved that as the sun falls behind the range we decide it is time to turn back. At the village entrance, three middle-aged men swear by Allah they have seen his footprints. Or thought they might have seen him.

Mize has deep frown lines, tiny eyes. It is a face shaped by the seasons. I want to see the school. We walk through the village. An overpowering smell of fresh hay stacked on plank-roofed huts. “This is the school. The children are here, one, two hours, then they go to work.” The room is tiny, the roof of wood. “They learn how to read here, start when they are seven, finish at 16.” He is ashamed. “It’s like a chicken-shed. We want it to be better. We do. But we are poor.” The state has given them a poster with pictures of the leader for the wall. A torn Cyrillic alphabet is stuck to its left. The room is heated by burning branches in a stove that could belong to 17th-century England.

Living close to nature, without thorough schooling, peasants have always been frightened of the mythical wild man. In the 18th century, the oppressed central European peasantry was gripped by a terror of aristocratic vampires in the run-up to the French Revolution.

The hysteria raged for a generation. Thousands of sightings were reported. Villages swore by Christ they knew what they had seen. The Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa was concerned enough to dispatch her personal physician to investigate whether or not vampires existed. They were not real, but poverty, oppression, ignorance and superstition were.

With political reform across the continent in the 19th century, the swarms of fairies, Woodwose, beasts and ghosts that had inhabited European minds for centuries slowly faded away. But in Romit, I touched a living myth.

And for Surob and the villagers the search goes on. “There is man who go up to mountains. Maybe he got a Yeti lady up there. We just need micro-sensors and web-cams. We can prove it. He’s out there.”

The Yeti shown above is by Harry Trumbore, from Loren Coleman’s and Patrick Huyghe’s The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates, 2006.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

There is a serious possibility of a team going out there next summer.Discussions are at a preliminary stage, but have been going on for a few months now.As ever, we will have to see how much it costs. The information in this article is very useful, in the meantime, so thanks very much!

I wouldn’t say Tajikistan is ‘new’ for research.

Dmitri Bayanov and Igor Bourtsev were going there as long ago as the 1970s.

In Bayanov’s book “IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE RUSSIAN SNOWMAN” Bayanov devotes a large section to that particular area.

In 1979 Bourtsev found a 35cm long track in the Hissar range of the Pamirs in Tajikistan.

In 1980 a further expedition included 120 people who spent a total of two months there. Researcher Nina Grinyova allegedly even had a close encounter with a creature whom she refered to as ‘Gosha’. Another member of that expedition had a much more brief long distance sighting.

Bayanov’s book is well worth reading for details of the above expeditions.

If they find one, may I suggest a name?: Stan.

Yes, this is most interesting. We had hoped to make it to Tajikistan this year, but the place in the Pamirs I wanted to go to proved to be inaccessible without either a helicopter or a three week horseback trek over the mountains.

Tajikistan has been investigated before, but this investigation is a newer one. If they do find one, i will be absolutedly surprised!

OK.

We have another Great Outdoorsman who gets into the backcountry; goes on a hike somewhat over his head; listens to people talk to him in like say their fourth-best language; and comes back saying, what fools.

I barely even skimmed this. And my summary is accurate.

No wonder this topic gets sneered at.