Cryptids of Haiti

Posted by: Loren Coleman on January 18th, 2010

Cryptids of Haiti

by Loren Coleman

With attention focused on Haiti since January 12, 2010’s massive 7.0 earthquake, I thought it might be instructive to conduct a quick overview of what cryptids have been discussed in the past from that island nation and the area nearby.

First, here is a bit of background about the biodiversity of the island.

In 1925, Haiti was lush, with 60% of its original forest covering the lands and mountainous regions of the country. Since then, the population has cut down an estimated 98% of its original forest cover for use as fuel for cookstoves, and in the process has destroyed fertile farmland soils, contributing to desertification. Realistically, that leaves very few acres of the tropical forest available for known animals, let along cryptids.

Since Haiti occupies the western third of the island of Hispaniola (with the Dominican Republic the eastern two-thirds), my survey will include a look at the cryptids reported for the entire island, as cryptids are not aware of political borders but only biological parameters. However, in the case of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, there may be a clearer dividing line than found in some other places in the world. See the photo below.

Satellite image depicting the border between Haiti (left) and the Dominican Republic (right), 2002.

Additionally, to understand where the animals (and cryptids) are, one must take into account the distribution of these forests, naturally. The climate of Hispaniola is generally humid and tropical resulting in four distinct ecoregions. The Hispaniolan moist forests ecoregion covers approximately 50% of the island, especially the northern and eastern portions, predominantly in the lowlands but extending up to 2100 meters elevation.

The Hispaniolan dry forests ecoregion occupies approximately 20% of the island, lying in the rain shadow of the mountains in the southern and western portion of the island (thus Haiti) and in the Cibao valley in the center-north of the island. The Hispaniolan pine forests occupy the mountainous 15% of the island, above 850 meters elevation. The flooded grasslands and savannas ecoregion in the south central region of the island surrounds a chain of lakes and lagoons in which the most notable include that of Lake Azuei and Trou Caïman in Haiti and the nearby Lake Enriquillo in the Dominican Republic.

What cryptids are significant for this island?

Caribbean Crowing Snake

Not to be confused with the Crested Snake Eating Bird, a form of the Basalisk, the major suspected cryptid from Haiti is the Caribbean Crowing Snake. In general, it is an unknown snake reported from a few places in the West Indies. Said to be four feet long, with a thick body, having a dull ochre color with dark spots, a pale red pyramidal crest like a rooster and scarlet wattles, one of its most unique features is that it crows like a rooster. Naturally, it eats chickens. The Caribbean Crowing Snake is reported from the eastern portion of Jamaica and Haiti. In 1829, a medical doctor saw a crested snake, dead and slightly decomposed, in Jamaica. A snake with wattles was shot in Jamaica on March 30, 1850, by the son of Jasper Cargill. (The primary source is Philip Henry Gosse’s The Romance of Natural History.)

Caribbean Monk Seal

New York Zoological Society, 1910.

The next cryptid is the Caribbean Monk Seal, a seal of the West Indies, which has been presumed extinct since 1952. Christopher Columbus saw these Caribbean “sea wolves” on the coast of Santo Domingo in 1494. His crew killed the first ones they saw and the destruction of the species continued by humans up through the 20th century.

First scientifically described in 1850 as Monachus tropicalis, these brown seals with gray on its back were recorded to be seven to eight feet long. They are said to be unaggressive and approachable. The cryptid sightings have been off Haiti and Jamaica. In 1997, sixteen out of 93 Haitian and Jamaican fishermen interviewed claimed to have seen at least one Monk Seal in the previous two years. Nevertheless, five major surveys of former Monk Seal habitats have been conducted by trained naturalists since 1950, with no definite evidence of its survival past the last confirmed sighting off Seranilla Bank in 1952. (Primary source is I. L. Boyd and M. P. Stanfield’s “Circumstantial Evidence for the Presence of Monk Seals in the West Indies,” Oryx 32, 1998: 310–316.)

West Indian Nesophontes

Clear evidence of the next cryptids have been found, and the search continues for these animals. Presumed extinct since the 17th century, the hunt is active for the Nesophontes (sometimes called West Indies shrews), which are insectivores of the West Indies. Members of the Family Nesophontidae, eight known species may still exist, including the Haitian nesophontes (Nesophontes zamicrus) of Haiti, and the Cuban nesophontes (Nesophontes micrus) of Cuba and Haiti.

These cryptids, the size of mice or rats, have a long snout, and, of course, eat insects. Besides being reported from Haiti, the search is on for them on Cuba and Puerto Rico. Fresh bone and tissue samples taken from barn owl pellets in Haiti in 1930 suggest a recent survival. Morgan and Woods wrote that some species survived until the early 20th century. The introduction of rodents and habitat destruction undoubtedly contributed to their demise. (Primary sources include, Gerrit S. Miller’s “Three Small Collections of Mammals from Hispaniola,” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 82, 1930: 1–10, Morgan, G. S., and C. A. Woods’ “Extinction and the zoogeography of West Indian land mammals,” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 28, 1986: 167–203. and Bruce J. MacFadden’s “Rafting Mammals or Drifting Islands? Biogeography of the Greater Antillean insectivores Nesophontes and Solenodon,” Journal of Biogeography 7, 1980: 11–22.)

Giant Cryptid Turtle

Sometimes cryptid giant turtles turn out to be real. Photograph of Hoan Kiem Lake’s Giant Turtle. Credit Vietnam.net

It is important to also mention that the Caribbean Sea south of Haiti has been the site of at least one well-discussed encounter with a large or giant turtle, mentioned, for example in Bernard Heuvelmans’ book and The Field Guide to Lake Monsters, Sea Serpents, and Other Mystery Denizens of the Deep (2003). The significant sighting for this region took place in early September 1494. As Christopher Columbus’ three caravels sailed east along the southern coast of the Dominican Republic, he and his crew saw a whale-sized turtle that kept its head out of the water. It had a long tail with a fin on either side. (Three sources are noteworthy, “The Life of the Admiral by His Son, Hernando Colon,” in J. M. Cohen, ed., The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus, New York: Penguin, 1969, p. 184; Bernard Heuvelmans’ In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents, New York: Hill & Wang, 1968, pp. 271, 564–565; and Ulrich Magin’s “In the Wake of Columbus’ Sea Serpent: The Giant Turtle of the Gulf Stream,” Pursuit, no. 78 (1987): 55–56.)

Chupacabras

Finally, the Latin American/Caribbean cryptid with the name translated from Spanish into English as “goat-sucker” must not be ignored for Haiti. While tabloid sensationalistic writers tend to talk about Chupacabras in Puerto Rico and Vodou in Haiti, the lore of the Chupacabras is not unknown in Hispaniola.

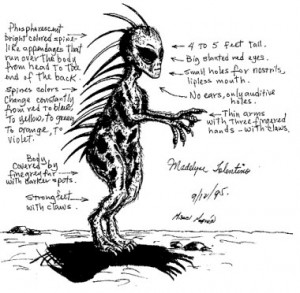

Indeed, the Chupacabras is said to be called Ciguapas in the Dominican Republic and Maboya (“evil spirit”) in the language of the original peoples of Haiti, the Taíno/Arawakan. Described as bipedal, alert, four to five feet, and covered in short, gray fur, with spiny hair, the nocturnal Chupacabras of Hispaniola are said to be livestock killers here as they are throughout the Caribbean. The reports, which are concentrated from Puerto Rico, are much more active for the Dominican Republic versus Haiti, however.

New Species Surprises From Hispaniola?

Are there any new discoveries of animals left in the supposedly well-explored island of Hispaniola?

As recently as 2001, what may be the world’s smallest reptile, the tiny (0.63 inch) Jaragua sphaero gecko (Sphaerodactylus ariasae) was discovered on Isla Beata, Dominican Republic, by S. Blair Hedges and Richard Thomas. Its size is comparable to S. parthenopion (0.71 inches long), found only on Virgin Gorda in the British Virgin Islands, which was discovered in 1965 by Thomas.

Credits: Ecology summaries from Wikipedia; cryptid insights from Mysterious Creatures (2002) by George M. Eberhart; Cryptozoology A to Z (1999); other references noted above.

+++++

Help Haiti

Needless to say, with the earthquake relief effort rightfully the foremost concern in the minds of those in Haiti now, cryptozoology is not even remotely on their radar. Nevertheless, for me, understanding the cryptozoology of the area gave me a clearer view of the whole situation.

If like me, you wish to assist the Haitian relief effort, click here to respond to Dominican Republic native David Ortiz’s appeal and the Red Sox Foundation’s promise that 100% of the donations received will be used to support UNICEF efforts in Haiti.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.