Cryptozoology’s Fathers

Posted by: Loren Coleman on June 19th, 2010

Happy Father’s Day to all the fathers out there.

But who is the “Father of Cryptozoology”? Actually, the debate over who is the “Father of Cryptozoology,” in reality, has raged on for years.

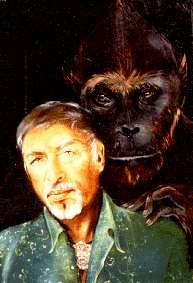

Illustration by Alika Lindbergh.

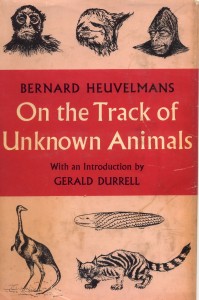

In 1955, Belgian zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans wrote a groundbreaking book in French, a now classic opus entitled (in English) On the Track of Unknown Animals. But in the 1955 French and the 1958 English editions, you will not find the word “cryptozoology,” in any language, in the text.

The first published use of the word “cryptozoology,” in French, occurred in 1959 in a book by wildlife biologist Lucien Blancou, dedicated to “Bernard Heuvelmans, master of cryptozoology.” At least, that is as far as we know.

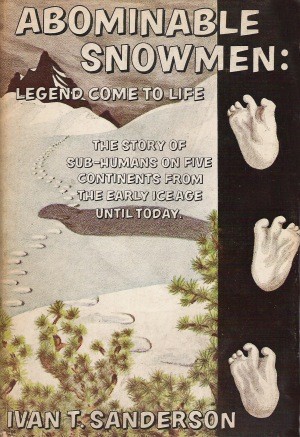

But should the candidate for “father of cryptozoology,” be the person who actually worked the word into print in the first English-language book? The premiere utilization of the term “cryptozoological,” in English, was in 1961, in Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life by Ivan T. Sanderson.

In Heuvelmans’s 1968 book In the Wake of the Sea Serpents, it is clear that the word “cryptozoology” had been around for perhaps over twenty years before it came into print in 1959. Speaking of two articles on water monsters written in 1947 and 1948 by Ivan T. Sanderson, Heuvelmans wrote: “When [Sanderson] was still a student he invented the word ‘cryptozoology,’ or the science of hidden animals, which I was to coin later, quite unaware that he had already done so.”

Intriguingly, this passage is missing from the French edition of Heuvelmans’ Sea Serpent book, and only exists in the English edition.

Heuvelmans is very open that it was Sanderson’s article in Saturday Evening Post in 1947, which stimulated him, Heuvelmans to undertake a study of unknown animals. After writing about jazz and doing some science articles, Heuvelmans was looking about for a project to devote his time and from which to obtain an income. He discovered that article, and thus stumbled into what would become “cryptozoology.” Ivan was the mentor to Bernard. But others have defended Heuvelmans’ status by noting he invented the “methodology of cryptozoology.”

Perhaps that is even in dispute, because the methodology for the surveying of the ethnoknown information from indigenous peoples has been around for a long time. Before there was cryptozoology, there was “romantic zoology,” which took as its objective to discover new animals based upon the testimony of native folks.

My friend and associate, Mark A. Hall, has made the case for some rather older “romantic natural historians,” as candidates for the first cryptozoologists and “fathers of cryptozoology.” Such names as A. C. Oudemans, Gunnar Olof Hylten-Cavallius, Karl Hagenbeck, Willy Ley, George Wendt, Rupert T. Gould, William H. Harkness, W. M. Gerald Russel, and Tom Slick, come to mind, although, of course, people like Russell and Slick were contemporaries of Sanderson and Heuvelmans.

Willy Ley, a popular author who Heuvelmans would have also been aware of in Europe, was the successful, popular author of several books published before either Sanderson’s or Heuvelmans’ appeared, including The Lungfish and the Unicorn: An Excursion into Romantic Zoology (1941), The Lungfish, the Dodo, and the Unicorn (1948), Dragons in Amber: Further Adventures of a Romantic Naturalist (1951), and Salamanders and other Wonders (1955). Exotic Zoology, published in 1959, and honored via Matt Bille’s title of his now-defunct journal, was the compilation of several chapters on cryptozoological topics from Willy Ley’s previous books.

Heuvelmans personally considered Oudemans as the first initiator of the field of Cryptozoology.

Who is your nominee for the “Father of Cryptozoology”? Or the “grandfathers”?

++++

If you would like to make a legacy donation to the International Cryptozoology Museum, your contributions go directly to our operating costs. Funding, new items, and time are always appreciated. If you would like to have direct contact about a major donation or becoming a volunteer with the director, Loren Coleman, please use the contact form here.

The ICM is a dedicated member of Portland, Maine’s Arts District and museum section of the city, and we encourage the patronizing of our neighborhood businesses, as we see the area change into a center for creative thought, adventure, and exploration. Thank you.

Deep appreciation, again!

The museum will be closed on Father’s Day, so we may be with our sons, who are traveling from far away to visit.

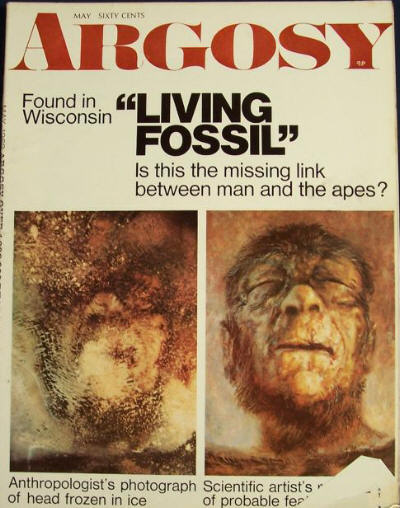

Ivan T. Sanderson’s and Bernard Heuvelmans’ mutual discovery, Homme Sauvage, from Guide Des Animaux Cachés (Guide to Hidden Animals), published in late October 2009, by author Philippe Coudray. One could say it was their “baby,” their “son.”

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

This question immediately reminded me of my work untangling the fathers of space travel, a topic I wrote a book on (The First Space Race, 2004). (And they were, as the social mores of the last century dictated, all fathers.) It’s interesting because space travel and and cryptozoology came to flower at the same time, the late 1950s. That gives rise to some interesting parallels.

The history of a field is always complex, but a handful of people stood out.

First came the great turn of the century theoretician, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Call him the grandfather. Without him, the field would still have emerged, but in fits and starts and much more slowly.

He laid the mathematical groundwork for turnign science fiction into reality and provided inspiration for the three fathers:

Hermann Oberth, who furthered the theory but, most importantly, was the first to explain the science in a popular book. Oberth also mentored and taught Wernher von Braun.

Robert Goddard, who turned the theory into the first liquid-fueled rockets and made hundreds of other advances.

Sergei Korolev, who turned the theory into the first Soviet rockets and carried that line of development through Sputnik 1 and Yuri Gagarin.

These men taught and inspired countless more in the modern generation.

In cryptozoology, I give the grandfather spot to Linneaus. He was the first man, anywhere in the world, to collect the entire available lore of creatures known and alleged and truly systematize it. That he went too far in accepting reports of things that turned out not to exist really doesn’t detract from his contribution. He was hardly the first important naturalist, but he inspired and empowered the generations of naturalists and then zoologists after him.

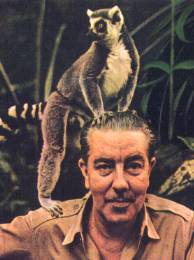

The three 20th-century fathers: Ley, Heuvelmans and Sanderson. To carry the analogy further, Ley is a bit like Oberth, the first popularizer, while Heuvelmans and Sanderson were also important popularizers but carried the work further: Heuvelmans, in theorizing and analysis, Sanderson in these areas plus in fieldwork. It is hard to imagine there is a cryptozoologist alive who was not inpired by one or more of these men.

That carries the parallels back to space travel. Every satellite engineer, rocket builder, astronaut, cosmonaut, etc. owes a debt to one of more of the fathers: Oberth (though his pupil von Braun may have been the direct inspiration), Korolev, who almost singlehandedly created the Soviet program by sheer force of will, and Goddard, the indispensable inventor.

So there you have it. I give the grandfather role to Linneaus and the inseparable role of fathers to Ley, Heuvelmans, and Sanderson (I am not quite sure where to put Oudemans.)

Thanks to Loren for bringing up this thought-provoking topic.

As a young person I lived in a very small town (Population 510) in Oregon. Our elementary school library contained only a couple books that really interested me; Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life, by Ivan T. Sanderson and a Bigfoot book with no cover I later found was written by Loren Coleman. I checked these books out continually for about three years. To me these are the “fathers” of cryptozoology. I have now read as many books on the subject as I can get my paws on. Sanderson’s and Coleman’s respective works seem to be the top shelf reference material I reach for. I am now a Biology major at Oregon State University. A special thanks to Mr. Coleman for making my childhood dream (of finding Bigfoot) something I know can be pursued through science, and giving academic merit to the fantastic!

-Happy Father’s Day

Well if you are considering the 19th century then Philip Gosse for his defence of the sea serpent (and interest in zoological oddities) as well as Edward Wilson who founded “the Zoologist”. Other relevant 19th century figures would be Oudemans of course, Frank Buckland (who was sceptical of sea serpents), and Japetus Steenstrup who was very interested in finding early potential accounts of giant squid.

Of course interest in controversial creatures as opposed to known creatures dates back to Renaissance and individuals like Pare, Kircher, Gesner and Aldrovandi. Prior to that it is difficult to ascertain whether animals are controversial or not.

But I would argue in fact by coining the term “cryptozoology”, Sanderson, Blancou, Heuvelmans or whoever invented the term actually did not do the topic any favours because by giving it a distinct name (rather than the “animal oddities” etc.) it allowed the topic to be marginalised in a way it did (and does) not have to be.

I first thought of the 19th century explorers. Then of Thomas Jefferson, then I realized that the compilers of medieval bestiaries probably qualify. They two were cataloging ethnoknown but unstudied animals based upon reports and traveler’s tales.

I think the answer here is subjective because there were a lot of people who kept this ball rolling. Linnaeus did indeed put down the list on the creatures of the world, but I don’t know if his was as much an interest in “cryptozoology” as it was to just create an account of every creature. Not sure.

Oudemans seemed to take more of an interest in things cryptozoological.

There’s no denying that a lot of people have not only kept cryptozoology evolving, but have worked to keep it in the eye of the “civilian.” Definitely the list up there–everyone has put their stamp on cryptozoology and deserves recognition for their efforts.

Bernard Heuvelmans is definitely at the top of the heap in cataloguing such creatures, however, his is one of those works I’ve only read after it was translated and re-released. Now, I have of course read a lot of him in excerpts in other persons’ works–B H has to be one of the most quoted men when it comes to cryptozoology works.

However, my first introductions to Cryptozoology were Sanderson, Dinsdale, Costello, and Gould thanks to my local library. In fact, the very first book I read as a kid was Monsters, Giants, and Little Men From Mars by Daniel Cohen. That and the In Search of series, and David Wolper Presents got me undeniable hooked on Nessie and the rest.

I think Bernard Heuvelmans extrapolated and advanced the cryptozoology arena, but I would have to vote for Oudemans as the Father of Cryptozoology.

On the other side, I’ll vote for Constance Whyte as the Mother of Cryptozoology who wrote “More Than A Legend” and summarized most of the Nessie lore.

Think Matt has offered a very intelligent, well-reasoned overall arguement. That’s always to be expected from him. However, I do have problems with his “nominees.” Maybe it’s just a lumper vs. splitter thing. Linneaus? Why not Konrad Gesner, or even Aristotle? I just don’t think the “Father of Cryptozoology” is exactly the same as the Father of Zoology.

Still, my nominations are almost the same as yours. I would suggest a troika, essentially a triangle as the modern “God-Fathers of Cryptozoology.

At the top of that triangle would be Willy Ley. In the 20th century he was the first famous, successful and widely read scientist to ever write about unknown animal mysteries. And without losing any of his scientific credibility, btw. . Like to think that encouraged both Sanderson and Heuvelmans. Anyway, those are my three “Godfathers.”

An interesting topic! I am particularly addressing Matt B and Charles’ comments. In the bookcase on my right I have Willy Ley’s “The Lungfish and the Unicorn”, 1948, next to his “The Conquest of Space”, 1949, with those amazing paintings by Chesley Bonestell. A book by the inspirational Patrick Moore is immediately to the right of it. In the shelf below is Francis T Buckland’s “Curiosities of Natural History” 1903. Thirty years ago I hiked up the hill to “Hanger Wood”, above the village where Gilbert White lived and wrote “The Natural History of Selbourne” in 1788.

I think Charles is right on target with his suggestion that “by coining the term “cryptozoology”, Sanderson, Blancou, Heuvelmans or whoever invented the term actually did not do the topic any favours”.

Whether it is called Natural Philosophy or anything else, the study of our environment is as old as humanity, and its mothers and fathers care not if their own names are remembered or not.

I would say that Hans Schomburgk (1880-1967) is also one of the little-known yet important fathers of cryptozoology. He did not only discovered the pygmy hippopotamus which was at this time a true cryptid and some other lesser known species, but was also for example the first one who brought an east-african elephant from Africa, discovered the tsetse-fly as carriers of disease. He collected stories about cryptic animals at the african natives and had also some own cryptozoological encouterns. He wrote several books from which “Zelte in Africa” (tents at Africa) is probably most important for cryptozoology, also because it includes some of the best information about the elusive water elephant.

I went for Linnnaeus because, while earlier naturalists and historians going back to the Greeks had collected and set down information, he systematized it. That included information on creatures which were ethnoknown, uncertain, or (as we have since learned) mythical.

This is a great discussion.

I placed Loren Coleman as one of the “fathers” of cryptozoology mostly for the detailed catagorization of not only the subject matter, but the people who study it. Just as Coleman’s Tom Slick: True Life Encounters in Cryptozoology, brought to light the millionaire’s incredible adventures, his Cryptozoology A to Z encyclopedia gives credit to the men and women in this fascinating field of study.