Japanese FeeJee Mermaids – Part I

Posted by: Loren Coleman on November 21st, 2009

NINGYO- The Story of Japanese Mermaids, Part 1

By- Brent Swancer

Mermaids. The word conjures up images of magical half human, half fish beings with beautiful maiden bodies atop elegant fish tails. These types of beings have been common fixtures in much folklore, myth, and legend around the world. Sailors from every corner of the Earth have long reported seeing and being enchanted by these enigmatic creatures in the waters of the far flung corners of the Earth.

As a nation surrounded by the sea, it is perhaps no surprise that Japan too has its own long tradition of mermaids. These creatures are known to the Japanese as ningyo (人魚), literally “human fish,” as well as gyojin (魚人), “fish human,” and hangyo-jin, (半魚人)or “half-fish human.”

Stories of fish-like humanoid beings have been reported around Japan for centuries. It is said that the first recorded account of mermaids in Japan dates all the way back to the year 619 during the reign of Empress Suiko, when one was allegedly captured in Japanese waters and brought before the court of the Empress herself.

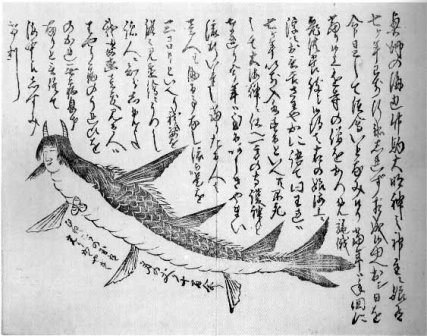

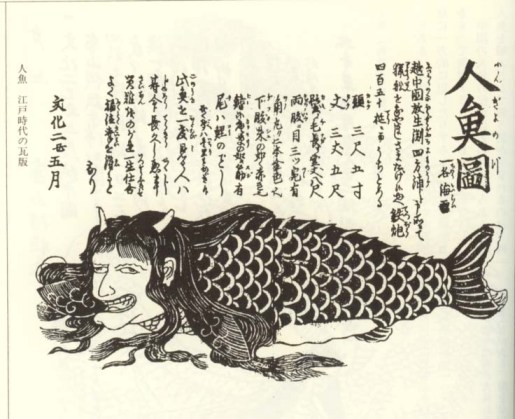

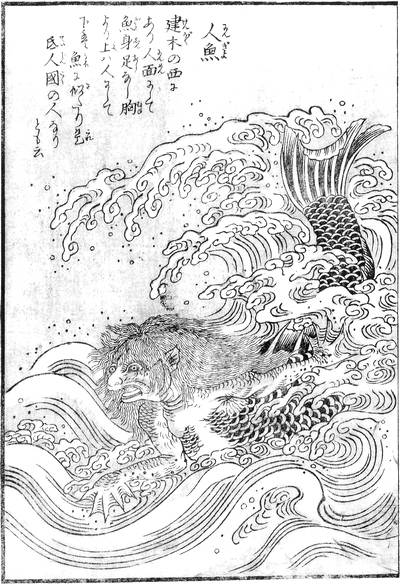

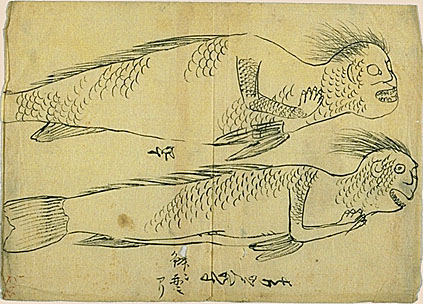

Physical descriptions of Japanese mermaids vary, however they generally differ in appearance from the typical image of the beautiful maiden torsos with fish tails common to traditional European mermaid lore. Before the influence of foreign lore somewhat changed the image of mermaids in Japan, the Japanese ningyo had little in common with their Western counterparts.

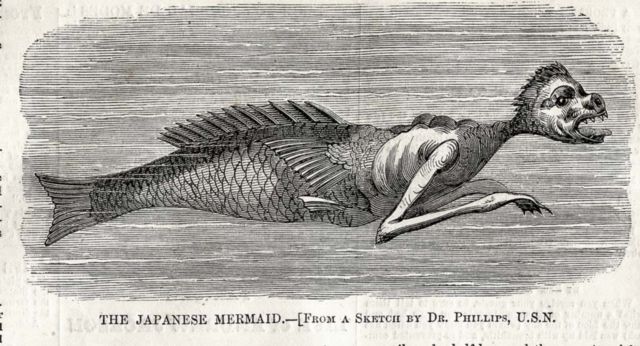

Although they were often described as having full heads of hair, the ningyo were typically depicted as more bestial and grotesque looking than the European variety, with an appearance more like a cross between a fish and a monkey than that of a beautiful woman. Often the mermaids had barely human scaly arms ending in claws. In many local traditions, these Japanese mermaids had no appendages, and were often said to be just a humanoid head upon a fish body instead of possessing full human torso. The heads were sometimes depicted as being horned, or possessing prominent fangs. Some stories tell of a more relatively normal looking human head, only attached directly to a full fish body. In some traditions, the mermaids retained a form reminiscent of the more familiar version of mermaids, but with a more demonic appearance or having distorted features. Japanese mermaids were sometimes said to have alabaster white skin and high, musical voices that sounded like a skylark or flute.

Many mystical qualities were attributed to the mermaids of Japan. The ningyo were believed to cry tears of pearl, and it was thought that eternal youth and beauty would be imparted upon any human being who consumed a mermaid’s flesh. Many legends tell of women eating the flesh of a ningyo and miraculously ceasing to age, or reverting to a younger, more beautiful form. Like many Japanese folkloric animals, merfolk were also said to have shape-shifting abilities. Mermaids taking on the form of human beings or other creatures are often mentioned in much folklore concerning the creatures. For instance, in the 1870s lighthouse keepers at the Cape Nosaapu Lighthouse in northeast Hokkaido believed that mermaids could turn into deadly jellyfish. These mermaids were thought to masquerade as beautiful, kimono clad women on shore that would lure men into the sea, upon which they would transform into giant jelly fish and kill anyone foolish enough to have gone for a swim with them.

For many Japanese in earlier eras, as in other parts of the world, mermaids were not figments of the imagination or the stories of crazed fishermen, but rather a very real feature of the ocean. Japanese fishermen were well acquainted with them, with sightings being fairly commonplace. Throughout the 16th to 19th centuries, it was not considered particularly unusual for fishermen to tell of seeing these enigmatic beings swimming alongside their boats or attempting to steal fish from their nets.

More relatively modern accounts exist as well, such as a case in 1929, when a fisherman by the name of Sukumo Kochi captured a fish-like creature in his net that had a human face upon the head of a dog. The creature broke free of the net and escaped.

Western explorers also gave accounts of seeing mermaids in Japanese waters. In 1610, a British captain saw one such mermaid from a pier at the port of Sentojonzu. The creature was cavorting in the water nearby and reportedly came quite close to the pier where the bewildered captain stood. The mermaid was described as being the head of a woman atop a body that was all fish, with a dorsal fin running down the middle of the upper body. Sea traders from the west would make note of mermaids in Japanese waters on many occasions in their logbooks.

Not only were ningyo regularly sighted by various seafarers, but tales abound of them being captured by fishermen all over the country, either by accident or by those looking to gain the purported immortality bestowing meat. In the 1700s and 1800s in particular, mermaids were often reportedly brought in by fishermen around Japan. The captured mermaids in some cases were said to have the ability to speak, and would try to trick their captors or talk the fishermen into releasing them. Although many of these mermaids managed to break free, not all were so lucky.

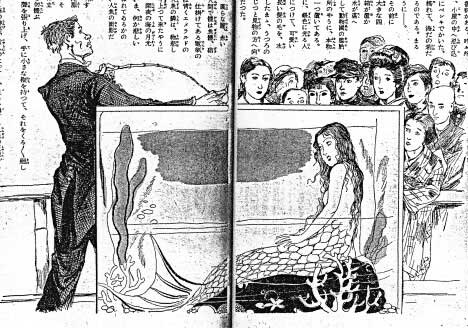

Among the Ningyo successfully caught by fishermen, some were said to be exhibited in sideshows. In 18th and 19th century Japan, sideshow carnivals known as misemono were quite popular among the populace. These events were like festivals of sorts that featured a wide range of attractions such as acrobatics, dance, fortune telling, and arts and crafts. One very popular type of attraction were exhibitions of strange natural phenomena. These were typically booths comprised of a “cabinet of curiosities” type exhibitions showcasing bizarre animals, plants, and other exotic wonders of nature from all over the world. These booths can be seen as being in many ways similar to the circus sideshows of the U.S. and Europe, attracting curious onlookers with their displays of the mysterious, strange, and sometimes downright freakish.

One of the biggest draws of the misemono sideshows was when mermaids were displayed. These typically dead and preserved specimens drew in huge crowds of people clamoring to get a glimpse of a real mermaid, and many of the exhibitors became wealthy from such shows. Whether any of these specimens were in fact real mermaids or not is not known for sure, but they certainly were quite real to those that saw them. Most common people of the time already considered mermaids to be real, and seeing one in front of their eyes only reaffirmed this notion.

The success and popularity of the misemono sideshow mermaids increased the demand for such attractions. A significant amount of money was changing hands, and some enterprising fishermen consequently began to see an opportunity to make some good extra money by crafting their own mermaid specimens. After all, why go out and go through the trouble of catching a real mermaid when you could make your own? Typically these fake mermaids were cobbled together from the upper torso of monkeys and the lower bodies of fish, as well as all manner of parts such as fur, skin, and membranes, joined in such a way as to avoid detection by the naked eye. These fakes turned out to turn quite a profit, and the increasing presence of more Westerners in Japan willing to pay exorbitant prices for these specimens only increased the trade in fake mermaids.

With regards to trying to discern any grain of truth behind these first mermaid exhibits, it is unfortunate that the one thing Japan became known for concerning mermaids was their ability to manufacture them. The Japanese, long known for mermaid exhibitions in their own country, became renowned overseas for being master craftsmen of fake mermaids, and there is much evidence to suggest the regular manufacture of such curios.

It may sound as if anyone who could be convinced by a such a monstrosity as a monkey sewn to a fish must be extremely gullible, but that would be underestimating the skill and ingenuity some Japanese displayed in these creations. At the time, many Japanese fake mermaids were incredibly convincing to the majority of those who saw them, and even some experts were confounded. An issue of The American Journal of Science and Arts from 1863 describes the craftsmanship of these fake mermaids thus-

“We should judge that the Japanese must have considerable knowledge of the lower animals to be able to produce factitious congeries, so nearly agreeing with nature and so well calculated as to deceive even practiced naturalists.”

As their popularity increased, Japanese mermaids began to pop up all over the place. A typical description of a Japanese made mermaid is written of in the book Curiosities of Natural History by Francis Trevelyan Buckland, in this letter from 1866 from a correspondent of Land and Water.

“Captain Cuming, R.N., of Braidwood Terrace, Plymouth, has returned from Yokohama, bringing with him a great variety of curiosities. Amongst them is a mermaid. The head is that of a small monkey, with prominent teeth; a little thin wool on the head and upper parts; long attenuated arms and claws, below which the ribs show very distinctly; beyond these latter the skin of a fish is so neatly joined that it is hardly possible to detect where the fish begins and and the monkey leaves off. The fish has large scales, spines on the back, a square tail, and appears to be a species of chub. It is quite perfect except the head, which only seems to have been removed to make the joint. Total length about sixteen inches; color of monkey, dull slate; the fish, its natural colour; and the whole in excellent preservation.”

It’s interesting to note the praise given to the craftsmanship on display, a common sentiment regarding the fake mermaids of Japan. Also noteworthy is the small size of the specimen. Most Japanese made mermaids were far from human size, with most being under three feet long.

Another well known specimen was shown at the Oriental Warehouse of Farmer and Rogers in Paris that was 25 inches long. It was described by one observer as follows:

“The lower half of her body is made up of the skin and scales of a fish of the carp family, neatly fastened to a wooden body. The upper part of the mermaid is in the attitude of a sphinx, leaning upon its elbows and forearm. The arms are long and scraggy, and the fingers attenuated and skeleton-like. The nails are formed of little bits of ivory or bone. The head is about the size of a small orange, and the face has a laughing expression of good nature and roguish simplicity. I cannot say much for the expression of her ladyship’s mouth, which is a regular gape, like the clown’s mouth at a pantomime: behind her lips we see a double row of teeth, one rank being in advance of the other, like a regiment of volunteers drawn up in a line. the hind teeth are conical, but the front ones project like diminutive tusks. I am nearly certain as I can be that these are the teeth of a young cat-fish- a hideous fish that one sometimes sees hanging up in the fishmonger’s shops in London. Her ears are very pig-like, and certainly not elegant, and her nose decidedly snub. The coiffeur is submarine, and undoubtedly not Parisian: it would, in fact, be none the worse for a touch of brush and comb.”

The observer later goes on to describe the following:

“At the back of her head we see a series of nobs, which run down the back till they join with a bristling row of 24 spines- evidently the spines of the dorsal fin of the carp like fish. The ribs are exceedingly prominent.”

An issue of the Saturday Magazine of June 4th, 1836 describes another such specimen that was displayed in a glass case in London that had “the skin of the head and shoulders of a monkey, which was attached to the dried skin of a fish of the salmon kind with the head cut off, and the whole was stuffed and highly varnished, the better to deceive the eye.”

Although this particular mermaid was allegedly taken by a Dutch crew from a native Malacca boat, it is likely that it was Japanese made due to the apparent quality of the craftsmanship.

Many of these faked mermaids were exceedingly clever and creative in their design, with the artists using all manner of various animal parts and often taking great artistic license with their creations. One specimen shown at Picadilly in London was found to be made up of a fish tail, ape body, the jaws of a wolf fish, the skull of an ape, and the fur of a fox. Some even had wings attached that were apparently fashioned from those of bats. Again, the quality of construction was so good as to require very careful examination and a keen eye to discover even the vaguest signs of human tampering.

It was quite common for Japanese mermaid specimens to be carried around in special wooden boxes. One such box that contained a mermaid had an inscription in Japanese claiming that the specimen had been captured and kept alive for two days before dying, suggesting that live specimens were sometimes obtained and exhibited as well. Indeed, as spectacular as the exhibitions of stuffed specimens were at the time, there was even a case of a purported live Japanese mermaid put on display. In 1825, a supposedly living mermaid from Japan was shown at Bartholemew’s Fair in London. The attraction brought in droves of amazed, gawking onlookers who could nt believe their eyes. The creature seemed truly spectacular until closer inspection determined that the “mermaid” was in fact a woman with the skin of a fish painstakingly, artfully, and no doubt uncomfortably, stitched to her skin.

Please stay tuned for part 2 of this article, where we will continue to delve into yet more of the past concerning Japanese mermaids, and have a look at perhaps the most famous fake mermaid of all time.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.