Flashback: Grover Krantz

Posted by: Loren Coleman on July 21st, 2008

Now and then, it is good to pause and remember those who have passed into cryptozoology history. Anthropologist and Sasquatch hunter, the “Dr.” has left the house.

Grover Krantz is recalled for many things, perhaps mostly by Cryptomundo readers for his research captured in the pages of Bigfoot Sasquatch: Evidence. To me, of all the men in the field I’ve met, he may have been one of the most gentle, most down-to-earth guys searching for Bigfoot, despite an overblown public counter-reputation for being sharp, fierce, and full of ego. To know Grover, as a person, was to truly like him.

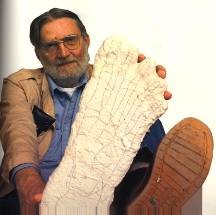

Grover Krantz, during the 1970s.

Through face-to-face encounters, phone calls, and emails, Grover and I kept in contact for many years. I tried to capture his life in various places, such as the brief biographical sketch of him I included in 1999 in my Cryptozoology A to Z or in his obituary I wrote. One of the last interactions we had was when I obtained his reconstruction of the Meganthropus skull, a treasured item in my collection. It was good to add those “bones” from Grover to my others, needless to say, and now that skull is on exhibition at Bates College.

I actually was honored and humbled when National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered” ask me to come on two days after Grover passed away on Valentine’s Day 2002, to praise and remember him. Grover Krantz, Ph. D., was a significance figure in cryptozoology and hominology, and he is missed.

But now, he’s back. Teaching again.

In a long, thoughtful article in the Washington Post, on July 5, 2006, there’s a touching and loving (yes, loving) visit with Grover Krantz.

Washington Post Staff Writer Peter Carlson does not let Krantz’s 2002 passing get in the way of his firsthand visit with Grover. He writes:

In a dim hallway in the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History, anthropologist David Hunt opens a dingy green cabinet and pulls out a drawer full of human bones.

“This,” he says, “is Grover Krantz.”

As most of us know, Grover left his bones behind when he died, as the article nicely puts it, so he could keep teaching after his death. This article, over several pages, does a great job re-visiting Grover. As the Post item mentions, there’s something very special about this collection of remains:

…only one skeleton in the collection came from a human being who was a friend of many Smithsonian scientists. They studied with Grover Krantz, drank with him, laughed with him.

Go visit the Washington Post site and register, if you want to read the entire piece (link is at the end). It talks about Grover’s wild Berkeley parties, his dogs, his anthropology career. On Cryptomundo, of course, I want to point out the sections that deal more exclusively with Grover’s interest in Bigfoot and how that changed his life, all for the good.

Here’s how the topic is first brought up.

Krantz was a legend in anthropology circles — and semi-famous in the wider world, too, as the eccentric professor who drove around the Pacific Northwest with a spotlight and a rifle, searching for Sasquatch.

Of course, Grover didn’t exactly do it that way. But he did surround himself with a world in which Sasquatch seemed a fitting component. It is probably not a coincidence that Grover Krantz lived and loved Irish wolfhounds too, dogs that the Vikings kept and gigantic on their own. The article spends a lot of time on how closely Grover grew to his dogs, especially Clyde, whom he wrote a book about and whose bones are stored with Grover’s.

Then the article comes back to “Searching for Sasquatch,” telling of how Grover…

…did archaeological field work in China and Indonesia. He wrote learned books titled The Process of Human Evolution and Climatic Races and Descent Groups. But when he became famous, it was for his hobby — chasing Sasquatch.

Living in the Pacific Northwest, Krantz heard lots of stories about the apelike “Bigfoot” creatures rumored to reside in remote forests. Curious, he chased down the rumors, interviewing alleged witnesses, analyzing photos, making plaster casts of footprints supposedly left by Bigfoot.

Slowly he came to believe that Sasquatch might exist, and he said so in several books. Naturally, that attracted a lot of publicity, which did not help his academic career.

“He was slow to advance to full professor, because they thought he was embarrassing the university with the Sasquatch thing,” says [University of Idaho anthropology professor Don] Tyler. “Grover was extremely stubborn. He could have played it better politically. But that wasn’t him. If he believed he was right, he did what he wanted.”

In 1981 a Colorado woman named Diane Horton read a story on Krantz’s search for Sasquatch in a Denver newspaper. A water quality inspector with a master’s degree in biology, she wrote him a letter asking intelligent questions. He wrote back. They began a correspondence, then met at a scientific conference. About a year later, they married.

“He was just delightfully refreshing,” she recalls. “I was 37 and he was 49 and we were both divorced, and it was nice to meet somebody who had a brain and sense of humor.”

When he married Diane, Grover told Tyler: “This is it. This is gonna be the last one.”

He was right. His fourth marriage lasted, although it wasn’t easy living with him and his Irish wolfhounds and his skeletons. Diane tolerated his eccentricities, but she drew the line when he wanted to search for Sasquatch in his homemade ultralight flying machine.

In 1998 he retired, and they moved to Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. And then he got cancer. As his big, strong body melted away, he pondered a question only an anthropologist would ask: What should I do with my bones?

He wanted somebody to use his bones the way he used bones — as teaching tools.

He called Dave Hunt at the Smithsonian. Hunt agreed to accept Krantz’s skeleton and to keep it with the bones of Clyde, Icky and Yahoo.

Grover died on Valentine’s Day 2002. At his request, there was no funeral. Instead, his body was shipped to the University of Tennessee’s “body farm,” where scientists study human decay rates — valuable information for detectives and coroners investigating murders.

In 2003, his skeleton arrived at the Smithsonian and Hunt laid it in its final resting place — in that pale green cabinet, just below the drawer that holds Clyde.

“Some of his students have gone there to see his skeleton,” Diane says. “It was a type of closure for them.”

She hasn’t made any visits yet. “I’m not ready for it,” she says.

The article then overviews how Grover’s bones are being used in teaching and how his colleagues may donate their bones to the Smith

sonian when they die.

Diane Horton, Grover’s widow, may do that, too. “I probably will, but I haven’t done the paperwork,” she says. “I’m either going to get cremated or I’ll join him there.”

Then, remembering the dogs, she corrects herself. “Join them .”

She likes the idea that somebody could learn something from her bones. But there’s another reason, too.

“Dave Hunt says that if I went there,” she says, “Grover and I could be the first couple.”

To read the entire article, if it is still archived, goggle some keywoords above or try the Washington Post, Wednesday, July 5, 2006, on page C01, click on “Using His Cranium: Grover Krantz’s Last Wish Was to Remain With His Friends. And He Has.”

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Help with the move into a separate, more open space for the museum! Please remember to donate to the museum as you think about what kind of future you want, and today you may directly send a check, money order, or, if outside the USA, an international postal money order made out “International Cryptozoology Museum” to

International Cryptozoology Museum

c/o Loren Coleman

PO Box 360

Portland, ME 04112

Please “Save The Museum”! Easy-to-use donation buttons are now available here or merely by clicking the blank button below, which takes you to a donation site without you having to be a member of PayPal. Thank you, everyone!

Remember the International Cryptozoology Museum.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Quite noble of Dr. Krantz to think of how he could donate his body parts while dying of cancer. It’s cool and sort of creepy at the same time to think you can still visit him, among possible Sasquatch friends…

He built an ultralight flying machine to hunt Sasquatch? That’s <em>awesome</em>!

What a guy. I sometimes wish I could have met and known Grover. Fascinating guy to listen to. Never boring.

Ah, Grover Krantz was, in my opinion, one of the greatest cryptozoologists ever. The only problem in his book was his obsession with the idea that there was a sasquatch in Barnum’s circus, which is based on a case that few, if any, other researchers have regarded as real.

I have peered into this very cabinet. Dr. Krantz must have been a large man–his femurs were very long and robust.

Have you seen Dr. Krantz skeleton, Loren?

Dr. Krantz was the first person I saw whose views on the sasquatch and the explanations of the footprints made me ponder the possibility of the animal instead of just plain skepticism.

It was a shame that he had to bear the brunt of the academic world and ridicule of his views from his peers for his views on bigfoot, and that it cost him dearly at the college where he worked.

Krantz was one of those few people I would have liked to have met and known. Not just for his insight on things bigfoot, but he struck me as someone who would have just been a hoot to be around. My prayers and thoughts still go out to his wife and family.