So You Want To Be A Cryptozoologist?

Posted by: Loren Coleman on February 28th, 2012

Revisit and read a good blog from 2007: Can I Be A Cryptozoologist?

About Loren Coleman

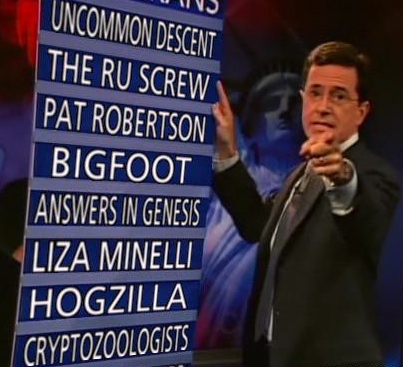

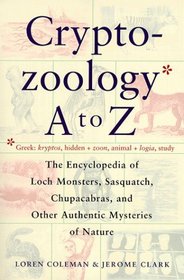

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

ROFL this is hillarious new article 🙂

Is there any concern amongst those that call themselves cryptozoologists that they might be a little presumptuous in defining themselves as “cryptozoologists” considering that zoologists have to have a four year degree in order to consider themselves zoologists? I understand that someone with writing talent and only a mediocre knowledge of zoology can pass themself of as an expert on “cryptozoology”, but is there a nagging concern in “cryptozoologists” that if they were held to the same standards as zoologists, as far as scientifc knowledge is concerned, that they would come up embarrassingly short?

I’m Pro-Cryptomundo and appreciative of Loren Coleman et al.

But “cryptoraptor,” do you even know all the degrees of all the people that write on this site? Those of the people who make comments?

I have a degree in anthropology, minor zoology (= physical anthropology concentration, therefore), a masters in the psychiatric field, and doctoral work in anthropology and sociology. But all people think about me is as maybe a blogger, or a writer, or a television interviewee. Readers never think about the scientific degrees of “cryptozoologists” nor even those of the people who peer-reviewed a paper they are reading in a scientific journal.

Nevertheless, there are some people in Sasquatch studies who deserve to be called “a cryptozoologist” or “a hominologist,” just as some undegreed or undereducated people are called detectives, artists, and birders.

I do not like the word cryptozoologist. In my opinion it is presumptive irrespective of whether one has a degree or not. It is a form of self-titling within our community that I have never understood. I make it a point whenever I am asked if I am a cryptozoologist to say I do not use that term, but prefer to be called a cryptozoological investigator which I most certainly am.

I would love to do cryptozoological work. And yes having a degree in a related field of study can be helpful (Loren Coleman has his education in Anthropology, Josh Gates of Destination Truth has a degree in archeology, Jeff Meldrum is a Physical anthropologist, and so on), but I don’t consider it a necessity (My brain is not hardwired for the intensive math you need for Zoology and many other, if not all fields of science, but I do havy research on the subject and others for the fun of it).

However, wanting to be one and being able is another matter. I don’t have the resources yet to pull it off. But one day, by the Grace of God, I will.

The bottom line is that qualification or no qualification i am certain that there are hardly any jobs around that pay for this. I don’t expect to see ‘cryptozoologist vacancies’ at my local job agencies.

Great article and that’s really credentials impressive Loren!

Thanks for posting this for us btw 🙂

The problem with cryptozoology is that zoologists should ALL be cryptos, and almost none of them are.

If I’ve said it here once I have said it a hundred times.

The only appropriate way for a scientist to respond when anyone asks about ANYTHING that isn’t proven – including mummies walking at night; crop circles; ghosts; pyramid power; AND Bigfoot – is: I await the proof, and wish the searchers luck. Kindly refrain from smirking; it does nothing for you, and may soon make you look foolish.

(If you are involved in the search, it’s allowable, of course, to talk about the evidence.)

I tell people who don’t believe there’s a God that that is no more rational than believing there is one. What is the evidence for either proposition? “Believing in” ANYTHING – including the nonexistence of something – is not rational. One has evidence; or one has nothing.

It’s not cryptos’ fault that mainstream science has left the field vacant. Scientists forsake their science, routinely, when crypto is the topic; in other words, they act ignorant and invalidate their degrees. If it is presumptuous to call oneself a crypto without a zoology degree, then presume, with attitude and an automatic weapon. Because scientists aren’t using their degrees either, when this is the subject.

It is forbidden for a scientist to scoff, period. To do so is contrary to the very frame of mind – questing, and holding NO untested assumptions – that makes one a scientist.

So you want to be a cryptozoologist?

My advice:

– Get that degree; it helps you evaluate evidence.

– Evaluate the evidence. Never scoff. Arm yourself instead.

– When others scoff: bring them up short with the evidence.

– Prepare to employ the courage of your convictions. Big time.

If you don’t have that degree, can’t or won’t get one, and want to call yourself a cryptozoologist anyway:

Bully. If you aren’t going to look for cryptids, who is?

Serves the scientists right. Tell them to act like scientists before they get all preachy about degrees.

I completely agree with my fellow posters opinions & statements thus far on this.

Personally, my opinion is that a degree is unnecessary in pursuing, enjoying, participating, and contributing to the field of cryptozoology.

Most certainly there are types of degrees that are beneficial; but required…no.

I’d much rather have someone with:

(and again, all of this is strictly my own personal opinion)

——————————————————

1) An open and analytical mindset:

I believe that one of the most detrimental characteristics to learning/studying anything is closed-mindedness; and that’s not just cryptozoology, that’s life in general. It’s all too easy to fall into the trap of “blind belief”/faith”, or the contrary – “blind denial”.

Keeping an open mind, and examining the things, that interest you, as objectively as possible is imperative.

Inherently, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with faith, opinions, and beliefs; however if they escalate to the level of ‘obsession’, then they cripple the ability to perceive and analyze information in an effective manner.

2) Interpersonal & Communication Skills:

I find that you (fellow cryptozoologists, forteans, enthusiasts; or whatever label you choose to describe yourself with) can be one of the most valuable assets to the study and enjoyment of cryptozoological pursuits.

In that regard, I find that effective interpersonal & communications skills are a fundamental ability. It doesn’t matter whether you are ‘out in the field’ conducting research and interviews; or are discussing topics with your peers; their value is the same.

It is inevitable, in any pursuit, disagreements will happen. However, I truly value the peers that have the ability to articulate their ideas (regardless of agreement vs. disagreement) without resorting to ad hominem assaults, name calling, threats, etc.

Disagreement is no reason/ excuse, to belittle, degrade, or otherwise alienate one’s peers; Doing so does not advance one’s stance or ideology; and only serves to hurt the overall community.

3) A desire to contribute in some way.

One of the greatest strengths we have is our diversity!

There are a large number of skills that people can, and do, bring to the table. It really doesn’t matter if your skill is photography, videography, engineering, zoology, botany, chemistry, investigative journalism, writing, law enforcement, hunting….the list is endless…..

Degree, or no degree, I don’t believe it matters. I believe what matters far more is simply the desire to contribute in a constructive way.

This is cool! I have a skeptic friend who scoffs and now I can really nail him for it.

If you are a cryptozoologist, as soon as you find what you’re looking for, you aren’t a cryptozoologist anymore. You’re a zoologist with a marketing job.

I would say follow your path and study crypto on the side. If you’re already inclined towards biology, zoology, or veterinary medicine, that’s great. If you’re a writer, business major, marketing, engineering or whatever, and that’s who you are, you should pursue that and see how it may apply to this field a little later. I’m a mechanical engineer, and find myself in a very relevant position to make contributions through those skills, in my own ways. Serious research endeavors may require all the disciplines mentioned above and many others.

I had a long interesting discussion one time with a guy who did not have any degrees, while I did, and we were both arguing about how much worth the “degree” had. I still don’t know that we ever came to a consensus (incidentally he was arguing in favor of having the “degree” and I was the opposite–ironic?).

I don’t know that having the piece of paper that says you’re educated in a particular field is what is important (maybe in the scientific arena, but that’s another story), so much as what you do with it. I know for my own self, while I do not have a degree in zoology, I have learned an awful lot and have read several of the text books required for the zoological path. Not to mention psychology and anthropology. While I don’t have the credentials, I think of myself as a “cryptozoological investigator–thanks John Kirk–I like that analogy. I put in the time and the research, testing my ideas against what we know in the various fields to try to come up with answers.

I would consider someone who gets out in the field and walks the woods, sits by lakes, etc. in the same bracket–some research is done in the field and some is done in the lab. Either way, what you’re trying to get to is the truth. Not what you think should be the truth, but what is the truth. And I agree with DWA ( I know, I know, I usually do:)–all zoologists should be cryptozoological investigators–they should be interested in the anomalies and the things that don’t fit. That’s what exploration in the field is all about.

springheeledjack- That is a very interesting thing you said and I’d like to add to it.

I do have a degree in biology, and while I feel I am competent in my areas of study (basically the effects of invasive species in island habitats), I sometimes feel just as stumped and lost as anyone else when it comes to cryptozoology.

I have also had immensely rewarding and insightful exchanges, many of them right here on Cryptomundo, with people who do not have any relevant degrees in scientific disciplines such as biology and zoology, that pertain directly to cryptozoology. We are in somewhat uncharted territory here, looking at things that often sit squarely outside of established paradigms and current scientific understanding. To that effect, I have found that untrained eyes can often provide fresh insights and approaches to these mysteries. Those without a scientific degree often are thinking outside of the box and often come up with quite brilliant solutions, approaches, and hypotheses in this field.

While I do think that like my esteemed fellow Cryptomundian DWA mentioned, a relevant degree can help you evaluate evidence and data in a rational and meaningful manner, as well as give you a solid backbone of knowledge pertinent to the natural world, it is certainly no magical way to the answers we are all seeking here. I would never hold my degree over anyone’s head or claim it somehow makes me any more right than anyone else.

Neither does a degree in science mean that you are actually doing science. This requires a completely perfect unbiased mentality, which is something hard to achieve with such flawed creatures as ourselves. If anyone thinks that scientists are somehow above bias or are always completely rational, then I have some news for you: they certainly are not. Preconceived notions can and do often have an effect on how evidence or data is approached or evaluated, and this can very often hinder the very science they are trying to achieve.

You can see this even within cryptozoology sometimes. For instance you may have two equally “qualified” scientists, at least in terms of education, with one firmly leaning almost into “true believer” territory, while the other is a steadfast skeptic. Both with hold their degrees high and proclaim the validity of their hypotheses, and all the while it may be the case that neither one is truly looking at the evidence and data in a truly rational or unbiased way.

I think self-taught naturalists and cryptozoologists who have read up in the relevant areas and even better have spent time in the field actually looking for the answers can offer extremely valuable insight and data. I never judge anyone here on what degrees they have or don’t have, but rather on what they say.

It happens. We are human. So the way I think that a degree should be approached is as a tool. A degree is a tool, and a tool is only as effective as the one wielding it.

I will say, though, that those with degrees are more likely to be given more consideration by the mainstream scientific community at large, and therefore gain this field the validity and credibility it needs to get the scientific attention (see: Funding) that cryptozoology so desperately needs. I wouldn’t say the mainstream will agree with what we say, they don’t even agree with each other most of the time, but having lots of Meldrum’s certainly gives us more scientific credibility than lots of Biscardis.

This is an exciting field, full of a vast amount of potentially game changing research. I think anyone here should be happy to be here learning, sharing, and being a part of that, degree or not.

I would also add to what I previously stated by saying that another area where I think a degree relevant to cryptozoology can help is in giving an individual knowledge of how science, its methods and approaches, actually work. This can be a hard thing to firmly grasp without specific training and experience, yet it is extremely important.

Science is an immensely powerful tool (again, a tool, only as good as the one who wields it), and is the best way we have of understanding the universe around us. It often pains me to see potentially good research or even a good discussion derailed due to an unscientific approach or thinking. Likewise, it saddens me when I see anyone here rail on science as somehow being the enemy. This is an untenable position that I have never thought made any sense. People who don’t look at the evidence properly, or are dismissive, or disregard or cherry pick data may be the enemy, but science itself certainly is not.

Science does not scoff or dismiss. It merely provides an excellent framework of methodology for evaluating evidence pertaining to how the natural world works and providing a way through which to find the answers we as human beings have desperately craved since the Stone Ages.

And it works. Everything we now know and take for granted has been arrived at in one way or another due to science. There is no reason at all to think that it will not be a method to guide us to understanding in the dark areas that we currently do not understand. Science is often not perfect. Mistakes can be made and staunch adherence to paradigms can hinder progress, but this is only due to the human element, not the idea behind science itself.

A degree can sharpen this tool and provide the knowledge needed for looking at these mysteries we face with a scientific approach. It is possible of course to have a good understanding of science without a degree, but a degree certainly doesn’t hurt. Likewise, there can be those with degrees in scientific fields who choose to largely ignore this approach in favor of other questionable ways of thinking. However, a strong understanding of science is certainly a powerful and indispensable tool in this field.

OK, mystery_man.

Now that you’re here, I better de-fang my post somewhat. 😀

Crypto’s most powerful advocates – I would hope it goes without saying – are the scientists degreed in relevant fields who have risked reputations on their adherence to the power of evidence and the scientific method. I haven’t met Meldrum, but what I have read of him has impressed me above all with his skepticism, his unwillingness to tread in any direction that evidence does not at least suggest. Mainstream paleontologists have engaged in flights of fancy over fossil remains, by comparison.

(And let me say as a long aside that such flights are necessary to the progress of science. Dialogue moves ahead as straw men are set up for dissection. Sometimes the necessary ground for debate is laid by a bold opinion. Science isn’t supposed to be boring! As somebody once said: if the numbers are boring, you have the wrong numbers. The science of cryptids exceeds in thrill factor anything happening on “Finding Bigfoot.”)

The cryptozoologists I have met reek of scientific seriousness. Having talked to them, I wouldn’t bring any silliness around Alton Higgins, John Bindernagel, John Mionczynski, or Loren Coleman. Cryptomundo is supposed to be a fun site; a lot of stuff is up here to generate hits. But it’s hard to do much reading here and not start really thinking.

But much of that thinking is being done by non-scientists. Too much of the zoological mainstream treats crypto like the plague. When I get steamed at science, it’s at scientists who pronounce without evidence. They can’t (says science):

1) Say something is “probably” not true, without citing percentage probability and supporting evidence;

2) Say something doesn’t exist, then, instead of the answers to “why do you think that?” start posing questions (“Why hasn’t anyone found a body? Why hasn’t anyone shot one? Why hasn’t anyone hit one in a vehicle?” Um, they have, sir/madam; and I have no more reason to doubt them than to trust you);

3) Respond to an appeal to them, as the experts, with a response that ignores the evidence, because “expert” means “know-it-all” and they’re afraid of the words “I don’t know.”

Too many scientists comfortably commit these sins. The ones cited above don’t; and you don’t either, m_m. So there’s a lot to build on while the mainstream slowly (glacially) warms to the topic.

But the field can’t wait for the professionals. Cryptids are just as subject to the judgments of evolution as anything else. We must find out what we can while we can; and it’s the amateurs on whose larger-than-life shoulders the eventual scientific discoverers will stand.

And as you said in different words: Science is an almost perfect discipline. If there are problems, they tend to lie in the people practicing it.

DWA- No need to defang your post. 🙂 I thought what you said was just fine.

I share your frustration with the “know it all” attitude of those highly educated in scientific fields. This has never made much sense to me because science is a field concerned with finding answers to how the natural world works, which by definition means things we don’t know. If we knew everything, we wouldn’t need science anymore.

We are far, far from knowing everything, and a know-it-all attitude is not conducive to finding the answers we seek. It can be frustrating to be sure, but take comfort in the fact that not everyone in scientific fields thinks like that.

One thing I would say is that sometimes hard questions aimed at ones ideas by the scientific community are not meant to dismiss or attack, but are rather to chip away at what is real and what is not. Even within the “mainstream,” which is actually in this day and age of new, far out research a tenuous term to define in and of itself, any data and research is subjected to a barrage of peer review, hard questions, and criticism. Especially new hypotheses that sit outside of current understanding can be subjected to a Darwinian process of cross examination from many sides.

This is usually a good thing and is indeed a hallmark of science, because anything that is left standing after being probed, questioned, and dissected from all sides has that much better chance of being close to the truth. It should not be seen as a hindrance, but rather as a way to weed out what is worth looking at further and what is not. This is why peer review is of such importance in science.

So I am not really bothered by being asked the hard questions in cryptozoology, and with the background I have, I tend to ask the hard questions myself. It does not mean I am dismissing evidence or ideas, but to the contrary means I am trying to find out more in order to get to the truth. It is absolutely necessary to ask hard questions.

In this regard, I think “Where is the body?” or “why hasn’t anyone shot one?” or “Where are the fossils?” and so on are perfectly valid questions that can help us understand more. Where I think a problem can come up is the spirit in which these questions are asked.

If someone asks “Why hasn’t one been hit by a car?” this is a valid question provided that the one asking it has a genuine interest in and is willing to consider the answer in a fair way. It is not a scientific question if the one asking this has already made up their mind as to what the truth is and is merely posing the question as an attack or a reason to dismiss the existence of something they have already decided does not exist.

So I think the questions you mentioned are not the problem. They are valid and worth trying to answer. The answers to such questions get us closer to the truth. But these are only good questions when asked in the spirit of discovery and an honest attempt to consider and evaluate the answers.

So in a nutshell, hard questions are good. Questions to bolster preconceived notions that are unlikely to change regardless of the answers are bad.