Tengu

Posted by: Loren Coleman on April 3rd, 2009

The Tengu

By Brent Swancer

The mountains and forests of Japan have long been the domain of the legendary Tengu, one of the most famous and ubiquitous creatures in Japanese folklore. The Tengu was a bird-like creature of the sky and trees, and they were seen as a protector of the mountains. Tengu are related to similar folkloric creatures in China, and likely have some influence from the “Garuda,” a bird-man from Hindu lore that was later adopted by Buddhism as a protector deity. They were often said to favor Cryptomeria trees, which are known for their aromatic wood.

Tengu were often seen as mountain gods, but there are many traditions for what they are. They are variously described as being cursed humans, demigods, demons, spirits, or a separate race of living beings.

Tengu were said to be hatched from eggs, like birds, and stories abound of travelers coming across Tengu nests filled with their giant eggs high in the remote mountains. One egg was said to be enough to feed an entire family, but few would dare to disturb them for fear of the Tengu’s wrath. Tengu have been known to possess a wide array of supernatural powers, including teleportation, telepathy, premonition, thought projection (they were thought to be able to invade a person’s mind and drive them insane), and shape shifting.

Tengu were said to be able to take the form of a man, woman, or child, but were most fond of taking the shape of a monk or elderly mountain hermit. In some areas, Tengu were thought to be able to take the forms of tanuki (raccoon dogs) and kitsune (foxes), which were also known as shape shifters. It is even suggested in some traditions that foxes and raccoon dogs were not in fact shape shifters themselves, but rather alternate forms taken by Tengu.

Tengu translates to “Heaven Dog,” but this name is misleading as the they look nothing like dogs. It is thought that the name “heaven Dog” was derived from a somewhat similar creature in China that was known as the “Tiangou,” or “celestial hound.” It is not known for sure why these Chinese creatures were called this, but one hypothesis holds that they were named after a devastating meteor that hit China somewhere around the 6th century BC.

Accounts describe the tail of this falling meteor as looking like the tail of a dog, hence the name “Celestial Hound,” and the powers of destruction that were associated with these creatures. There are various hypotheses proposed for why these Chinese “Tiangou” became the “Tengu” of Japan, but it seems that at least the name has its origins there.

The most common modern image of Japanese Tengu is not of a dog at all, but rather that of a humanoid, bird-like creature with a very long nose, a human’s body, arms, and legs, yet possessing wings and feathers. The contemporary Tengu is often depicted as looking more or less like a human warrior monk with wings and an abnormally long nose, and frequently with deep, red colored skin. However, in the long histroy of the Tengu, they have undergone somewhat of an evolution in both form and purpose.

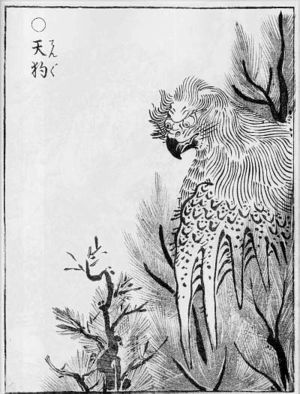

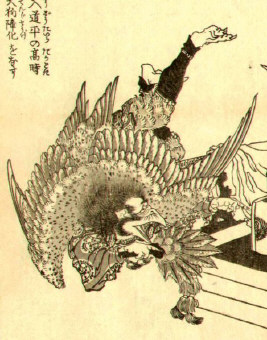

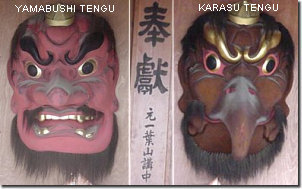

The original incarnation of the Tengu was animalistic, more avian than human, and was typically portrayed as looking variously like anything from simply a giant bird of prey, to a vaguely humanoid form covered in feathers, with wings, piercing eyes, a compact head with a prominently beaked face, and heavy, vicious looking talons. They are depicted both with clothing and without. These animal-like beings were known as the “Karasu Tengu,” or literally “Crow Tengu,” although they could just as often look like eagles or other birds. The Karasu Tengu were known as evil creatures, prone to abducting children, starting fires, and savagely killing anyone foolish enough to do damage to their forest lair. These were violent creatures, said to enjoy ripping travelers limb from limb, and they were thought to be heralds of disaster, war, and doom wherever they went.

In later times, the Tengu underwent a gradual transformation, becoming increasingly more anthropomorphized over time. The beaks became humanized into long, sometimes hooked noses, and the bodies became more clearly humanoid in form. These more human-like Tengu were often depicted holding feathers in their hand, and wearing a monk’s garb. These later versions became known as the “Konoha Tengu” or “Yamabushi tengu,” which means “mountain monk Tengu.” The Tengu became increasingly known as great warriors, skilled martial artists, and expert weapon smiths. In fact, they were often given the reputation of being the best martial arts instructors. In addition, they were gradually seen as more benign creatures, even helping, or protecting humans. Whereas the more ancient forms of Tengu were said to abduct children, the later, more benevolent Yamabushi Tengu were often enlisted to help find missing children. The Tengu still maintained their love of war and fighting, but their overall evil reputation was softened. In some cases, these Yamabushi Tengu were seen as coexisting with the earlier Karasu Tengu as their leaders.

All forms of Tengu were known to have a mischievous streak to some extent. They were known for deceiving and playing tricks or pranks on humans, or sometimes kidnapping people only to disorient them and set them loose to see what would happen. It was said that shoguns would sometimes go so far as to formally request that any Tengu leave the area in advance of important visits in order to reduce the chance of embarrassing incidents. There is even a scroll at a temple in Shizuoka prefecture which allegedly contains a written apology penned by a Tengu. It is told that the creature was captured in the 17th century by the high priest of the temple and forced to write the apology after harassing travelers in the area.

Other such relics related to Tengu can be found in temples around Japan. For instance, the Hachinohe Museum in Aomori prefecture houses the alleged mummified remains of a Tengu. The skull of these remains is humanoid, while the body is covered with feathers and the feet are like that of a bird. Another temple in Saitama prefecture keeps what is said to be the talon of a Tengu, while still another supposedly has the beaked skull of one.

Is there any grain of truth at all behind any of these stories? Does the Tengu have any cryptozoological significance? Of course the sword wielding, magic using, telepathic, winged humanoids seem far fetched, but what of the earlier versions of the Tengu? It seems at least worth considering the cryptozoological possibilities behind this creature’s origins.

One hypothesis that has been suggested is that stories of the Tengu could have perhaps been influenced by birds that had demonstrated some sort of physical abnormality. For instance, there are quite a few documented cases of four legged chickens. This sort of defect could maybe give the bird the appearance of having arms as well as legs. Perhaps this sort of abnormality could even have been seen in other birds such as crows as well, which would certainly give new importance to the term “Karasu Tengu.” Four legged chickens bear little resemblance to even the most avian looking Tengu, but perhaps deformities such as this had something to do with early stories of bird-like Tengu, which then became imbued with more folkloric elements and human characteristics over time and subsequent generations.

What about other possibilities?

When trying to find answers, there seem to be some parallels worth exploring between the story of the Tengu and that of another well known phenomenon, the Mothman, which was made popular in large part due to John A. Keel’s book, The Mothman Prophecies.

Mothman, 1966-1967: Artist Bill Rebsamen, from Mothman and Other Curious Encounters.

Not only do the Mothman and Tengu resemble each other in physical appearance, but there are also similarities between the transformation both creatures underwent from earlier to later versions. In the case of the Mothman, there were the original eyewitness reports of a bird-like creature that later became the more humanoid, supernatural creature popularized by Keel. This later transformation into the more humanoid, paranormal, and generally more outlandish Mothman championed by Keel conflicted with the first eyewitness reports of winged creatures that could have been more grounded in cryptozoology. With Mothman, It seems likely that what started out as sightings of a possibly real animal became something more with Keel’s involvement and perhaps further embellishment by later eyewitnesses.

Garuda postcard, from India. Credit: Doug Skinner.

It is also worth noting that in addition to the physical similarities between Keel’s Mothman and the humanoid “Yamabushi Tengu,” even some of the supposed supernatural powers later attributed to Mothman are mirrored in the Tengu. Like the later version of Mothman, Tengu were also at times considered harbingers of disaster.

The Virginia Tech’s Hokie Bird football mascot (directly above and below) is semi-comic, but it is also called “Blacksburg’s own Garuda” at VA Tech, giving a hint of tragedy too, to the creation.

Although the time frames are different, it seems at least possible that a similar process could have been at work in the gradual evolution of the Tengu from its animalistic “Karasu” form to the increasingly more humanized “Yamabushi” forms of later times. Both Mothman and Tengu started out as winged mystery creatures that were more bird-like in their beginnings, and both share the current popular image as flying, winged distinctly humanoid beings. As fantastic as these current versions may seem, could there have been a real animal at the core of the origins of both of these creatures, indeed perhaps even behind many of the other winged humanoids reported around the world? If the story of Mothman could possibly have had its beginnings in sightings of a real animal, could the same not be true of Tengu? These similarities between the transformation of Mothman from winged cryptid to paranormal winged humanoid, and that of Tengu from animalistic versions to more humanized versions, both possessing increasingly vast supernatural powers, are worthy of consideration.

Even if the culprit was merely a large owl, as is often argued in the case of Mothman, there could be a similar influence on the early versions of Tengu as well. Japan is home to one of the largest species of owl, the Blakiston’s fish owl, which has a wing span of up to 180 cm (6 feet). Under the right circumstances, an owl this large seems like it certainly has the potential to give rise to sightings that, in conjunction with Buddhist folklore and mythology brought over from China, could fuel stories of something like the Tengu. Although the Blackiston’s fish owl is found only in Hokkaido today, perhaps it once enjoyed a larger range in Japan that we are not aware of. There are also other species of owl in Japan, such as the long eared owl, and an exceptionally large specimen could possibly have had something to do with the early accounts of Tengu as well. It seems worth considering that there could have even been some currently unknown species of large bird at work.

In the end, we are left with a perplexing question. Is the Tengu simply pure fabrication, myth, and fantasy, or is there perhaps something more to it? Could a real animal have been at the core of this legend?

The Tengu has such a prominent place in folklore and traditions in Japan, and is so steeped in supernatural imagery, that it is hard to say where the truth ends and the myth begins. However, considering the possible cryptozoological origins in the case of Mothman, as well as known animals of Japan such as the badger, fox, and raccoon dog, that over time were given a similarly mythical status and fantastical abilities, it certainly is interesting to speculate about.

##############

Your contributions to the research is greatly appreciated. Only $80 has been received in the last three weeks. Even your $10 donation assists in conjunction with that from others. Thank you.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

Thank you, Brent! I’ve actually been waiting for this one! Excellent piece, I’ve long been fascinated by the Tengu. I didn’t know about the possible connection with Garuda though. As I read your article I had another thought occur to me: What about the mythical bird-people of other cultures, such as Harpies and whatnot? If we were able to go back far enough, would we find similar origins to the Tengu, Garuda, Harpies, Roc (Rukh), and even Thunderbird? Birds have also long been associated with good or bad omens and portents, or good or bad luck, or even just symbols of good or bad stuff.

The tales of Tengu kidnapping children makes me think of the modern reports of eagles or unknown large birds carrying off children, which is actually where I started to wonder about similarities and connections.

Of course this sort of speculation can also lead far and wide into wondering in general about similarities of various myths worldwide in olden days.

Anyway, nice article. Learned some things I did not know. I eagerly await your next piece. Good work.

Hi Brent, fascinating article, and why I assume we have Garuda Indonesia airlines ?

Ceroill- Thank you very much for your words of support. I’m happy you enjoyed this article and could learn something! I actually think you may have been the one who requested I do a piece on the Tengu, which is what led me to write this.

Yes, the Garuda connection is very interesting, and I find it fascinating how the Tengu was influenced by other cultures such as the Chinese with the Tiangou, and Hindu lore with the Garuda, which could have been built upon an actual animal at some point. I mentioned it briefly in the article, but I also think that many of the winged creatures of other cultures could have been influenced in similar ways. Winged humanoids seem to be as prevalent across far flung cultures as hairy men and dragons are. Certainly similar origins could be at work.

I really like the connection you made between Tengu kidnapping children and the reports of giant birds carrying people off. That angle had not even really crossed my mind, so thank you for mentioning that. It is an excellent point, and only deepens the mysterious connections between these creatures. It really is fascinating to wonder if at some point in the past there could have been some kind of giant bird that either carried off, or was perceived to carry off children. Very good insight, Ceroill!

Anyway, I’ll try to keep my articles coming. 🙂

Human imagination. Is it the problem or the solution?

Thanks mystery_man.

The Tengu (and Crows) are also closely associated as patron spirits with the Ninja, with which they share many supposed qualities: they taught them their craft in the remote mountains.

Maybe this intertwining of myth and cultural group influenced the lore’s evolution to more humanoid, positive, magical, and warcraft?

Phoenix, interesting point. Allow me to mention that it has also been said that the ninjas arts originated with a disaffected Chinese warrior monk who settled in the mountains. Maybe that tale was spliced in with the older tales of the magical bird creatures, and this led to the anthropomorphizing of the Tengu over time? Just a thought.

I actually suggested this to you on another post some weeks ago. Like Ceroill, I was wondering when you were going to get around to THIS particular cryptid.

It’s funny…

In the middle of the 19th century, when the Emperor was touring Dai Nippon, there were still signs posted along certain remote places warning Tengu to keep away.

Ah yes, cryptidsrus, indeed you were the one who suggested this one! Yes, it was that request for a piece on the Tengu that actually got me thinking about writing this. At first, I wasn’t sure how cryptozoological this creature would be, but on further thought realized that there are a lot of avenues worth exploring with the Tengu that could have a basis in cryptozoology. Thanks for bringing this to my attention as something worth reporting on.

Pheonix- Yes, I was aware of the ninja connection, and it is fascinating how crows and Tengu were adopted in this capacity. In addition, the Tengu were often seen as sort of patron saints of not only ninjutsu, but of martial arts in general. Yet another interesting point to consider when looking at the humanization of the Tengu. I’m very happy with the good insights you and the other commenters here are adding to this subject.

Ceroill- As I told Pheonix, another good insight. I have no doubt that this could be yet another driving factor behind the anthropomorphizing of the Tengu. I wonder just what it was that caused people to attribute martial arts prowess to this particular animal (if it was a real animal at some point) in the first place?

Brent, are there any explanations for the Tengu that are depicted with the “Bob Hope – Richard Nixon” nose? In meso-American cultures the image of the “long nosed god” appears frequently. Even historic Indian tribes have this tradition of the “elder brother” who in ancient times who sported this schnoz. He was rather like Hercules battling monsters and giants sometimes through mystical means. Two god-like beings in different hemispheres with a Hope-Nixon nose…just an interesting coincidence, or some kind of ancient connection?

Alligator- I’m not sure of the origins of the long nose in meso-American cultures, but I may be able to shed some light on the significance of this feature in Tengu.

There are two main reasons for the development of the long nose in Tengu. One was the simple matter of the beak of earlier versions being made into a long nose in the more humanized versions. In this way, the face became more human, but retained some somewhat bird-like features with the schnoz. But there is a deeper meaning involved here as well.

In Buddhist beliefs, the long nose is related to the Tengu’s long held hatred of vanity and arrogance. Tengu were often thought to have contempt for priests or samurai that were narcissistic, vain, or pretentious, and singled them out for the most trickery and mischief. Tengu were also quite frequently used as a literary vehicle for criticizing such faults. In Japan, an abnormally long nose is indicative of arrogance or vanity. In some traditions, it was thought that when a particularly pretentious priest died, they would become a long nosed Yamabushi Tengu as punishment. This is one reason why over time Tengu folklore became so intertwined with imagery of monks and priests, and why the Yamabushi Tengu is often depicted wearing a priest’s clothing or taking the form of a monk.

I agree that it is interesting that two far flung cultures have a mythical being with the long “Hope/Nixon” nose. I’d be very curious to know just what the origins are behind the nose in those other cultures you mentioned.

Anyway, hope this is helpful and answers your question somewhat.

Mystery man – in Osage tradition the long-nosed “Elder Brother” is a wild man, contrary in nature. If he said ‘yeas’ he meant ‘no’ and so on. He maintained this wild streak until part of his nose was cut off in a fight, then he wasn’t so wild and contrary. The image of the elder brother in Osage iconography is almost identical to the one in Mississippian (900 – 1400 AD) iconography. So it seems safe to assume the tradition had been around for thousands of years. I never heard of his schnoz being tied in with a bird though. However, I learn something new every time I go to the reservation, so I won’t say there is no link. In some of the Plains tribes there were “contrary” warrior societies sometimes called Dog Soldiers. They did everything backwards until they were in battle – they were like the elite special forces in the Cheyenne, Lakota, Kiowa tribes, etc. They based their warrior ethic on the original contrary warrior, the Elder Brother, who looks an awful lot like the humanoid version of the Tengu.

MM, Alligator, here’s another interesting cultural cross connection regarding noses. It occurred to me as I read MM’s latest tidbit about the long nose being used to skewer vanity and ego.

Consider Cyrano De Bergerac. He was a real person who was proud of his large nose, and apparently dismissive of those who chose image over substance. The play about him rather exaggerates things, I’m sure. He was certainly a skilled satirist whose fiction poked at what he saw as problems of his day.

Anyway, just a bit of real world synchronicity about long noses and attitudes.

Ceroill, your remarks fit well with the description of the Elder Brother and why he ceased being so wild and contrary when his nose was clipped. Somewhere in the mists of distant time, some conception about long noses arose among human beings and became embedded in everyone’s lore. 🙂

The wings, the snout, and the plasticity of the descriptions made me think more of the Jersey Devil than Mothman.

This may be kind of tangential, but compare Japanese depictions of tengu with their depictions of Caucasians.

Likewise with the ‘elder brother’ in N.A., consider that the Clovis people were probably from Europe (though one should think of Saami or Euskadi, not Germans at that early stage) They being outsiders, and few in number, could well have been depicted as wildmen, and of course, with big noses.

“Dog soldier” meant cavalry. The N.A. natives only had dogs as domesticated animals, so when they saw horses, they used the term for dog which would be identical with ‘domesticated animal’ for them. This was translated to English as ‘dog’. “Horse soldier’ would have been a better translation. I’m not saying that they might not have had those other elements in their warrior society. I don’t know. I’m just talking about the name.

Some of the more bird-like depictions of the Tengu, as well as the photos of the 4 legged chickens, remind me of the gryphon in a way.

Great stuff.