Iriomote Wildcat

Posted by: Loren Coleman on February 26th, 2008

Today, I received directly from Japan, for the museum, the above shown replica of the Iriomote wildcat (Prionailurus iriomotensis), a classic animal of discovery for cryptozoology. It may be only a minor figurine at 2.5 inches long to some, but I find it significant that such care has been bestowed onto this important replica. A mere three decades ago, this cat found itself moving from the world of being a cryptid to a felid zoological reality.

The Iriomote wildcat remains a mysterious species, even now, years after its discovery, as evidenced in this recent essay below.

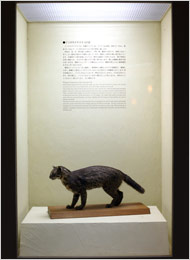

Unlike this stuffed Iriomote wildcat at a wildlife conservation center, live specimens are elusive and seldom seen. Photo by Ko Sasaki.

To protect the cat, a sign and a rumble strip alert drivers to slow down at a place where the animal is known to cross. Photo by Ko Sasaki.

An endangered species of wildcat survives only on Iriomote, a tiny, mist-shrouded Japanese island.

As a Japanese Island Grows Less Remote, a Wildcat Grows More Endangered By Noimitsu Onishi, The New York Times

Iriomote Island, Japan — The Iriomote wildcat is said to have roamed this small, subtropical island in the East China Sea for 200,000 years, but proved so elusive that it was not discovered until 1967. To this day, many islanders have never seen the wildcat, and some even stubbornly deny its existence.

One of the world’s rarest wildcats, it survives only here on Iriomote, one of Japan’s most far-flung islands. Almost indistinguishable from a house cat, the Iriomote wildcat is believed to be related to a leopard cat found on the Asian continent, to which this island was once linked.

In a nation where pork-barrel politics have paved over the country and dotted it with airports, Iriomote (pronounced ee-ree-o-mo-teh) can be reached only after a 35-minute ferry ride from neighboring Ishigaki Island and has a single main road hugging just half its coastline. Iriomote’s mist-shrouded, mountainous interior, blanketed by primeval forests and laced with mangrove-lined rivers, remains almost as impenetrable as ever.

Still, residents and tourists have increased in number in recent years, drawn by the island’s wilderness and by the wildcat itself, known here as the “mountain cat.” The encroaching development has added urgency to efforts to save the wildcat after Japan’s environmental authorities last year raised it one notch on a list of endangered species.

Researchers completing a census worry that the wildcat’s population has fallen below the 100 estimated more than a decade ago.

“It’s facing its biggest crisis ever,” said Masako Izawa, a wildcat expert at the University of the Ryukyus on Okinawa’s main island. Like other researchers, Ms. Izawa, 53, has spent years studying the animal without actually being able to see it, relying instead on photographs, videos and other secondhand evidence.

Though the wildcat is seldom spotted, its presence is felt everywhere on this island, including on buses, in restaurants and on bridges, all featuring images or sculptures of the animal. Signs on the island’s single main road, warning of wildcat crossings, are ubiquitous and manifold, vastly outnumbering cautionary road signs where children cross.

“Watch out for Iriomote mountain cats crossing,” reads one road sign with a drawing of the mottled wildcat. Others show a drawing of a leaping wildcat or a photograph with exhortations to “drive slowly, Iriomote.” Yet another type of road sign, with two red lights on top, displays a rudimentary, though instantly identifiable, sketch of the wildcat, with the plea that “there are mountain cats ahead — watch out!!”

With an average of three wildcats ending up as roadkill every year, the island’s two-lane main road — progressively widened to accommodate the increasing number of cars — has emerged as the main threat to the wildcat. The road meanders through the island’s inhabited lowlands, which happen to be the wildcats’ preferred territory.

The authorities have devised elaborate methods to help the wildcat cross the road unscathed. Even as the road has been widened for greater traffic and speed, new rumble strips called “zebra zones” induce drivers to slow down and alert wildcats to oncoming cars.

Eighty-five “eco roads,” or underpasses for animals, have been dug under the main road. Surveillance cameras set up at 19 of the underpasses confirm that wildcats are using them, though perhaps not as frequently as other animals, and perhaps not enough to offset other changes in recent years.

With most of Iriomote’s 110 square miles inaccessible to human beings, only 2,325 people live here. But even as the rest of rural Japan’s population has been decimated in the last decade, Iriomote’s rose 22 percent. What is more, the number of tourists surged by 33 percent in the past five years, reaching 405,646 last year.

“Human traffic into areas that human beings did not enter before is getting heavier,” said Chieko Matsumoto, 62, the leader of a private group that seeks to control the population of stray house cats, which can transmit diseases to the wildcat.

In its long history here, the wildcat has stood at the top of the food chain in a small, fragile ecosystem whose isolation and rich biodiversity have earned Iriomote comparisons to the Galápagos. On an island without mice, the wildcat eats everything from wild boar to shrimp.

“Many believe that Iriomote is too small an island to support the presence of such a carnivorous animal,” said Maki Okamura, a wildcat expert at the Iriomote Wildlife Conservation Center. “So it’s widely regarded as nothing short of a miracle that the wildcat has been able to survive as a species on this island for 200,000 years.”

Human traces have been found here dating back centuries. Coal mining brought settlers here a century ago, though malaria kept the population low. Today’s old-timers, like Kimiaki Fujiwara, 78, came here as children and tend to be skeptical of all the attention the wildcat is getting.

Mr. Fujiwara said he had never seen a wildcat in his 68 years here and actually doubted its existence. “I think they’re just house cats that ran away and are living in the mountains,” he said.

“I guess it’s all right to protect wildcats or whatever, but I’d also like them to protect people,” he said, adding that most of his neighbors lived on pensions. He was expressing an opinion often heard in his neighborhood on the island’s northern coast.

The old-timers’ ambivalence, and sometimes outright antipathy, toward the wildcats can be traced to a visit by a German feline expert shortly after the discovery of the wildcats in 1967. To save the wildcat, the German suggested forcing all humans off Iriomote.

The more recent tourist boom has exposed fresh tensions. Longtime residents tend to be farmers and have little interest in the wildcat. Newcomers operate tourist-related businesses that depend in part on the wildcat’s survival but may also threaten it.

As an indication of the fragility of the balance, a male wildcat crossing the island’s main road was hit and killed by a car on a rainy evening a few days after the interview with Ms. Okamura. The center had tracked the wildcat for three years and named him Googoo.

About Loren Coleman

Loren Coleman is one of the world’s leading cryptozoologists, some say “the” leading living cryptozoologist. Certainly, he is acknowledged as the current living American researcher and writer who has most popularized cryptozoology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Starting his fieldwork and investigations in 1960, after traveling and trekking extensively in pursuit of cryptozoological mysteries, Coleman began writing to share his experiences in 1969. An honorary member of Ivan T. Sanderson’s Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained in the 1970s, Coleman has been bestowed with similar honorary memberships of the North Idaho College Cryptozoology Club in 1983, and in subsequent years, that of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, CryptoSafari International, and other international organizations. He was also a Life Member and Benefactor of the International Society of Cryptozoology (now-defunct).

Loren Coleman’s daily blog, as a member of the Cryptomundo Team, served as an ongoing avenue of communication for the ever-growing body of cryptozoo news from 2005 through 2013. He returned as an infrequent contributor beginning Halloween week of 2015.

Coleman is the founder in 2003, and current director of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine.

i agree with the German remove the people and save the Cat.!

What?! The population is less than 100 estimated a decade ago? Sigh…

To look at an Iriomote Cat is almost to look back in time, because Iriomote Cats are probably close in appearance and behavior to some of the very first cats. I hope that their habitat can be preserved and that they can continue to survive in the wild, but I also think that some of them should be taken into captivity for breeding. Another possible way to increase their numbers would be through cloning and surrogate gestation.

Domestic cats have been successfully cloned. Embryos of Leopard Cats (to which Iriomote Cats are closely related) have been successfully implanted into female domestic cats, which carried the pregnancy to term and produced live Leopard Cat kittens. I do not know if this has yet been done with other small wildcat species, but if wild Iriomote Cats could be live-trapped, and tissue samples taken for cloning, the cloned embryos could then be implanted into domestic cats which could be sent to several zoos. The Leopard Cat tissue donors would be released back into the wild with no harm done. In this way, a captive breeding program could be implemented without reducing the wild population.

These are fantastic animals. Some years ago, I had the pleasure of making an excursion out to Iriomote island in the hopes of seeing one as well as studying its habitat. Alas, I did not see any and indeed, like the above essay states, some people who have made a full time pursuit of the cat haven’t even seen one in real life. I hope to go back there again someday.

This cat is so mysterious and elusive, it is hard not to feel a sense of thrill when out looking for it, even if you come up empty handed. The fact that this cat has survived on such a small island for so long is fascinating to me, and I was excited to see its natural habitat for myself. This island is small, but it is packed with some of the densest forest and vegetation you are likely to see, with many areas that are totally impassible by humans. After seeing some of those remote and thickly forested areas, I had no problem understanding why they are so rarely seen.

Even with the remaining amount of good habitat, I am concerned for the wildcat’s future survival for several reasons. First of all is the influx of new residents and especially tourists that was mentioned in the article. A few people I spoke to complained a bit about all of the new people coming and “over running the island” or “disturbing the peace” as they put it. More residents means more roads, which are a big threat to the cats, and more tourists mean more land cleared to accommodate facilities for them, in turn wiping out more of the cats secluded habitat.

Another threat that I didn’t see mentioned in this article is the effect that a particular invasive species is having on the wildcats. I’m talking about domesticated house-cats, which are fairly numerous on the island. Not only could they compromise the wildcat as a species through hybridization, they also prey on the same animals the wildcats need for food. The effect of this direct competition on the wildcats in an already fragile, small island ecosystem is huge. Domesticated cats are doing a lot of damage.

Things have to be done to preserve this species and soon, or I fear it will not be around in another decade at all. I agree with Kittenz, and think that some should be captured for captive breeding purposes. It would pain me to see some of the few remaining ones taken out of the wild, but in the end it would be for the species’ own good. I’d also like to see more preventative measures put into place such as the ones the essay mentions and more areas put under special protection. I’m not sure yet what measures I think should be taken about the domestic cat problem. Since these are people’s pets and as such typically more important to the owners than some elusive wildcats that they’ve never seen, it is a sensitive issue but it needs to be addressed as well, I think.

Ok the article did mention house-cats, but only briefly and only about the transmission of diseases. Diseases, direct competition, hybridization, three classic negative impacts of an invasive species the domesticated cats are posing on the wildcats. I commend the groups that go out to try and collect strays, but they do face hurdles. The same thick forest that hides the Iriomote wildcat can also make stray or feral cats very difficult to catch. Also, poisoning or trapping campaigns are not a good move since they can affect the very species they are trying to help.

So far, domestic cats do not appear to be interbreeding with the Iriomote Cats, mystery_man, according to all the published reports that I’ve seen.

You’re absolutely correct about the competition for prey and the possibility of diseases introduced by domestic cats – and other domestic pets such as dogs. It was domestic dogs that carried the canine distemper (a virus related to measles virus, which causes a deadly form of encephalitis), which wiped out three thousand lions in the Serengeti a few years ago. Lions – indeed all cats – had not been known to be susceptible to canine distemper, but apparently the virus changed in a way that made them susceptible. Since the disease was new to lions, they had absolutely no resistance, and they were ravaged by the disease. The implications for other wild cats are ominous. No one knows for certain which cats may be susceptible, but a wild Siberian tiger died from canine distemper just a few years ago. An epidemic may be imminent; we just do not know.

A similar thing happened in the 1980s when parvovirus hit the dog world. Parvo evolved from feline panleukopenia virus (“feline distemper”), a serious disease of cats which still kills millions of kittens every year. Some intermediate animal – a raccoon, maybe a ferret – contracted feline panleukopenia and the virus mutated to a form that dogs could contract. Dogs had no resistance and they died by the millions before a vaccine was developed. Parvo still kills thousands if not millions of puppies worldwide.

Mainland species of cats have lived with the chronic feline diseases such as FIV (feline AIDS) and FIP (feline infectious peritonitis) and FeLV (feline leukemia) for millennia, and they have developed some resistance (although, worldwide, those diseases kill thousands if not millions of cats every year). Island species such as the Iriomote Cat, which have been isolated for millennia, may not have such resistance.

Many people allow their domestic pets to have litter after litter of kittens, and the vast majority of those kittens worldwide are never neutered and never vaccinated. Given domestic cats fecundity, compared to that of wild cats, a few non-neutered cats can cause a population explosion within just a few years. TNR (trap-neuter-release) programs work much better for controlling feral cats populations that outright elimination of the cats. When feral cats are killed, new cats simply move in to take their places. But feral cats are very territorial, and when they are trapped, neutered and released, they keep their territories and do not tolerate other cats. Eventually most of the cats in a given area are neutered, and their population stabilizes. Feral cats usually only live about 10 years or so. It takes a long-term commitment, but in the long run, TNR programs work very well. Extermination programs only work if every last cat is eliminated – something that is nearly impossible to achieve, especially when there is also a human population who keep pet cats. Requiring mandatory neutering of all pet cats is a very good option, but if the people are poor they may not be able to afford that. Perhaps the government could create an incentive program, such as tax credits, to encourage people to spay their pet cats.

I have always been interested in the many small wild cats of the world. They are rarely seen and never on the big TV shows ( filming lions and tigers is cheap and easy). The world has spent $MILLIONS on tiger and there are thousands in the wild and many thousands in capivity , but no corporation or millionaire has a $ for a small cat species rarely seen. Est. ONLY 100 left!! In East Texas there are thousands of bobcats no one sees and they are still killed each hunting season for “personal trophies” .

Kittenz- That’s correct, it does not appear that interbreeding is a problem at this point, but it very well could become one. I don’t mean to get all doomsday here, but I personally think interbreeding will be seen in the future. The wildcats may start to try to mate with feral cats simply because there are no other mates of their own species available. With such a small population, and as a result a shortage of genetically distinct mating partners, interbreeding could quickly cause problems if it were to happen. Genetic diversity is an enormous problem facing the Iriomote cats considering not only are their numbers small, but those numbers are further divided by geographic isolation.

As of now, habitat destruction and disruption, as well as diseases (especially feline AIDS in recent days from what I’ve heard) and direct competition from domestic feral cats (dogs are a problem too, but the cats are more numerous on the island) remain the biggest threats to the Iriomote wildcat. As for disease, it has always been a scary and unpredictable thing with introduced species, the examples you gave being a perfect illustration of that fact. I could go on and on with other examples of my own involving sicknesses carried by invasive species. There is simply no way to fully predict the effect of introduced viruses upon often defenseless native species (and I would bet that the Iriomote cat is one of those defenseless ones). Any new germ brought into a new ecosystem is a potential Pandora’s box, really. As far as habitat destruction is concerned, it’s unfortunate that many of the coastal areas lie outside of National parks, yet are favored haunts of the wildcat. Too bad it is the coastal areas that are the most likely to be developed for tourism on the island.

As far as the neutering and spaying option goes, you have to realize that it is not done here in Japan on nearly the same scale as it is in the States. Many, many people keep un-neutered and un-spayed animals, mostly due to the prohibitively expensive prices, lack of awareness, and lack of any incentives. I am more surprised when I come across an animal that is fixed in Japan than vice versa. It will take a long term program and a lot of incentives to make that plan work with attitudes being what they currently are. The TNR method is a great idea if you can get the islanders to go for it, and more importantly, want to pay for it. The thing is, most islanders don’t really care about the wildcats enough for me to think they will support such a program with the financial backing and time investment needed. These are the kinds of problems that are facing efforts to control the invasive house-cat problem on Iriomote island.

I hope something can be worked out. The loss of the Iriomote wildcat would be a tragedy in more ways than one. Not only would we lose a precious species, but we would also likely see far reaching effects on the rest of the ecosystem. When you have an intrinsically linked ecosystem like that found on a small island like this, you can see rather pronounced “trophic cascading”, which basically means a ripple effect through the biosphere caused by the disappearance of a species. When the wildcats vanish, it could pose a variety of chain reactions throughout the ecosystem of the island.

In general, I think the TNR (trap-neuter-release) method is a good way to control, reduce, and eventually eliminate populations of feral cats and reduce their threat as an invasive species. It is humane, comprehensive, and long term. However, I do think there is a potential problem with it in regards to Iriomote.

The main problem I see with the use of TNR as a solution here is that this sort of management program typically works better in an urban environment, where the rampant breeding of cats is mostly a nuisance and having a colony of cats controlled through TNR is better than having an uncontrolled one. However, in a rural or wilderness setting like Iriomote island, a major problem posed by the feral cats is direct competition with the wildcats for prey items. By trapping and then releasing feral cats, they are free to continue to kill wildlife. Considering that some endemic species like the Iriomote wildcat are down to extremely low numbers (some estimates put their current number at as low as 40 individuals), we can hardly afford to allow these feral cats to go out and continue to do damage even for a short time, let alone the time it takes for TNR to show results. A long term proposition like TNR is not such an attractive solution in a wilderness area with critically endangered species present. In the time that it takes for the program to show benefits, the feral cats could have already caused irreparable damage to the fragile ecosystem of the island through this direct competition for rescources as well as preying on other rare species of smaller animals that could in turn cause a chain reaction within the habitat. I don’t think TNR is necessarily the best answer on Iriomote island.

While I’m not sure what the ultimate best solution to the rampant problem of feral cats in Japan is, there are some things that I think might be helpful to do. First of all, cutting off the supply of new animals is of utmost importance. The community needs to be educated about spaying and neutering, and more government subsidized programs to lower the costs have to be established. There have been some areas in Japan that have successfully introduced free neutering and spaying programs, but these are far from the norm. Spaying and neutering is still quite novel here, and even if it does catch on, it might not be enough. In Japan, many feral cats are brought in to new areas from far away and abandoned, a common practice here in a country that typically frowns on the unnecessary killing of animals. When people don’t want or can’t keep their pet anymore, they will often take it far out into wilderness areas and release them even though it is technically illegal. As a result of the tendency of abandonment, there is a continuous influx of new (almost always un-neutered or un-spayed) animals, which somewhat detracts from the efficiency of neuter and spaying campaigns. One prefecture combated this problem by actually putting up police checkpoints to check cars for people carrying cats that might possibly be released into the wild.

Another thing that could be done is to promote a system of mandatory identification and registration of all pets. In Japan, the housing conditions make it very difficult for people to keep cats indoors and outdoor cats are very common. As a result, it is difficult to legally require people to keep their pets indoors. If there was a solid registration system, not only could the outdoor animals be kept track of, the owners could be held responsible for abandoning their pets. One prefecture has experimented with creating by-laws requiring all pets to be fitted with id microchips, which is a good idea, but has technical problems to be overcome as well as practicality issues. One more little thing is I also think people need to STOP FEEDING FERAL CATS. You wouldn’t believe how much this happens in Japan and it really compounds the problem. Feral cats that get regular meals from sympathetic locals thrive and experience a sharper population rise. In the end, since Japanese statutes and ordinances lack any practical guidance for protection or management of cats, be they feral or owned, all such measures have to be considered on a city or prefectural level.

These are all measures that can be taken, but in the case of the fragile ecosystem of Iriomote, the best answer is the complete removal of invasive species such as feral cats. This is a tricky thing to do. The Japanese general public is not typically aware of wildlife management and at the same time consider killing animals taboo, so campaigns that kill the animals risk alienating the public and being met with harsh criticism. On the other hand, if the feral cats are trapped alive, who is to shoulder the burden of dealing with them? I suppose the only way would be to garner as much public participation as possible on trying to come to an agreement on what to do with the cats. Whatever happens, the most important thing is that a way be developed which the community can understand and support.

If consideration is given to cultural, social, and ecological factors, the problem of how to approach the feral cat problem in Japan is a complicated one with no immediately apparent solutions and no easy answers.

I forgot to mention that another problem I find with TNR (trap-neuter-release) on Iriomote is that the dense forest cover makes it hard to catch every stray or feral cat out there, and therefore there is no guarantee that all of the cats have been altered. Any that are not altered will continue to reproduce which could cancel out the benefits of the population that cannot reproduce. When you add the problem of people putting food out to feed the strays, you attract some unaltered cats (often un-spayed or un-neutered cats with owners that are drawn by the food) that can still reproduce, have a chance to mate with other unaltered cats drawn to the food (their fecundity has been mentioned), are well fed and healthy, yet still hunt native animals or wildcat prey species since cats will hunt even if they are eating well.

Like many posting here, I have long been fascinated by the Iriomote Cat, and am greatly saddened that their population has dropped so low. I would have to side with Mystery Man here and be pessimistic about prospects for its survival, despite my best hopes that it does so.

On a somewhat related note, island ecosystems the world over seem to be both incredibly rich and at the same time incredibly fragile. I have often wondered how many undiscovered species became the unknown (Perhaps I should say hidden) casualties of war in the Pacific, especially on such islands as Iwo Jima and Bikini that were basically blasted into defoliated wastelands. Since these were inhabited islands, surely some known and documented species were lost as well. It seems preposterous to me that you could do that to an island and NOT lose something unique, but I’ve never heard any such thing mentioned elsewhere.

Mnynames- Indeed island ecosystems are quite interesting for the reasons you described. They are fascinating to me. You are right that they can have incredibly rich biodiversity, sometimes surprisingly so, and it is a sad predicament that they also can be so fragile and easy to disrupt. You can imagine such disruptions in an island ecology as sort of like the ripple effect of throwing a rock into water. If you throw the rock into a large lake, the effect is relatively small or slow to affect the entire lake, whereas if you throw it into a small puddle, well you get the picture. Damage done to an island ecology can be have magnified effects throughout the habitat. I think it is also worth noting that often island species have evolved uniquely or that their isolation has “frozen” some species in time, allowing us to get glances of what some species might have once looked like, such as is the case with the primitive Iriomote wildcat.

I am also of the opinion that most likely there were unique and undiscovered species that were wiped out during the war. Who knows what sorts of amazing animals inhabited those islands that we will never know about? It is sad to think that although the animals may have been ethnoknown, they were eradicated before ever being fully brought to light as part of this planet’s rich biodiversity and natural history. I do find myself wondering what might have been lost forever on these islands due to horrific damage inflicted by human warfare.

Island habitats can be very sensitive to change. Since the habitat on Iriomote island is so small, and the population of wildcats so low, any sort of damage to their ecosystem, be it through human land development, roadways, pollution, or introduced species, is going to be far reaching and devastating. I’d like to be more optimistic about the fate of this species, but right now the way things are going over there on Iriomote, I don’t think the outlook is too good.